The Awl died. Or will die, in a couple of weeks. It was/is a website with the usual internet attitude – an awl, dear children, is a sharp pointed instrument for punching holes — but not the usual internet manners. My Twitter feed is full of writers who were young a few years ago, who are sad for the death of The Awl and grateful for the chance it gave them to say what they needed to and in the way they needed to say it. And they’re right, it was like a party in there, full of people with smart mouths and sharp eyes, funny and charming and sometimes boring and sometimes too revealing and you worried a little some might be self-destructive; but defying all human social tendencies, the party was friendly. It was intelligent, idiosyncratic, and inclusive.

The Awl died. Or will die, in a couple of weeks. It was/is a website with the usual internet attitude – an awl, dear children, is a sharp pointed instrument for punching holes — but not the usual internet manners. My Twitter feed is full of writers who were young a few years ago, who are sad for the death of The Awl and grateful for the chance it gave them to say what they needed to and in the way they needed to say it. And they’re right, it was like a party in there, full of people with smart mouths and sharp eyes, funny and charming and sometimes boring and sometimes too revealing and you worried a little some might be self-destructive; but defying all human social tendencies, the party was friendly. It was intelligent, idiosyncratic, and inclusive.

And when I say “inclusive,” I mean that they were, for a website that wasn’t a science website, open to including posts on science. I wrote for them for a bit, early on. I’d just written my third and fourth books back to back, had been underground for years, and when I came up for sunlight the whole publishing business had changed. It was 2010 and staff writers were fallling out of the sky, freelancers’ print markets were going out of business, and nobody knew how to make money on the internet. I stood there blinking in the sunlight, no ideas for another book, no ideas for stories even if I knew where to send them any more, wondering what to do next, and thoroughly sick of my own voice. At that moment, Heather Pringle called and asked if I’d like to start a science blog, and I said “Sure. What’s a blog?” So I started reading blogs and websites and found a lot of resourceful people saying mean things in a clever way — but don’t read the comments, I did and dear God, are these people even house-broken?

That’s how I found The Awl. It was run by Alex Balk and Choire Sicha, and though neither of them have run it for years now, I think they set up The Awl’s one-off combination of civility, humanity, and interestingness.

I dealt only with Choire. Here’s Choire, and I’m cut-and-pasting sections from his emails without his permission:

Me: Choire, do you want a post updating the post about Hanny’s Voorweerp?

Choire: DARLING!

Hello!

Hello from my underwater fish tank lair.

First order of business; who wouldn’t want this?

Second order of business: in the next few days things start calming

down and I want to talk to you!!!

Xo

Me: (later) Here you go, Choire.

Choire: OH!

I LOVE IT!

The Awl-mourners on Twitter talk about their favorite posts and the ones I remember best is a series of posts by excellent, generous, and sadly late, Dave Bry, apologizing in detail to every person he’d ever neglected or been rude to. The series was brilliant and so sweetly written and earnest that you felt you’d just apologized to all the people you’d been rude to.

The mourners also mention the comments section. The Awl commenters were not only civil, they were a sort of 4th Estate; you got the impression that the commenters were there to complement the writers, that The Awl was commenters + writers. That is, The Awl was what a blog ought to be, which is what writing ought to be: a conversation between two entities, neither of whom is expendable. I wrote a post once on physicists’ ways of estimating certainty and I don’t link to it now because it was made whole by the commenters’ applying estimates of certainty to their own lives, and for some reason, The Awl has removed all comments.

In 2010, we’d just started The Last Word on Nothing, some of us knew more or less what we were doing, and 200 viewers was a spectacularly good day. One post suddenly headed due north, straight up and when I went to morning-read The Awl, I saw that Choire had linked to the LWON post the day before. I wrote to thank him.

Choire: I actually sat down and made a routine for myself, a sort of jogging

path through the Internet, to ensure that I was going to cover the

things I wanted to this fall, and you were on it. Whee *jogs jogs

jogs*!

Me: If you will, please keep us on your jogging path — my

co-bloggers are writing emails titled HOLY SHIT. And thank you again.

Choire: Hmm you guys have SUCH A QUALITY WEBSITE, and I’m afraid the people who would read you just don’t know you well enough yet!

Me: Tell me what to do, Choire, and I’ll do it

Choire: Hmm well we’ll just INSINUATE YOU. That’ll be step one.

And so he did. He insinuated not only us but other websites and especially other writers, hundreds of them, especially young writers. Who does this? Somebody who knows in his bones how to make a community out of people who don’t know each other, who won’t ever meet, who now feel like the family home just got bulldozed, which is too bad but it’s still the family home.

Nobody still knows how to make money on the internet, except through foundation grants and salesmen; I remember when The Awl hired its first salesman and started paying writers, but apparently it wasn’t enough to last.

Me: Dear Choire, thank you, thank you, thank you. Our numbers are up. Thank you.

Choire: Well you know. There’s people we have to take with us!

Let me say that again: there’s people we have to take with us.

______

Photo of an awl: Krissy and Dennis, via Flickr

Another week, another week of great reading here at LWON. We like to think so, anyway. Here’s what you missed:

Another week, another week of great reading here at LWON. We like to think so, anyway. Here’s what you missed:

January 8-12, 2018

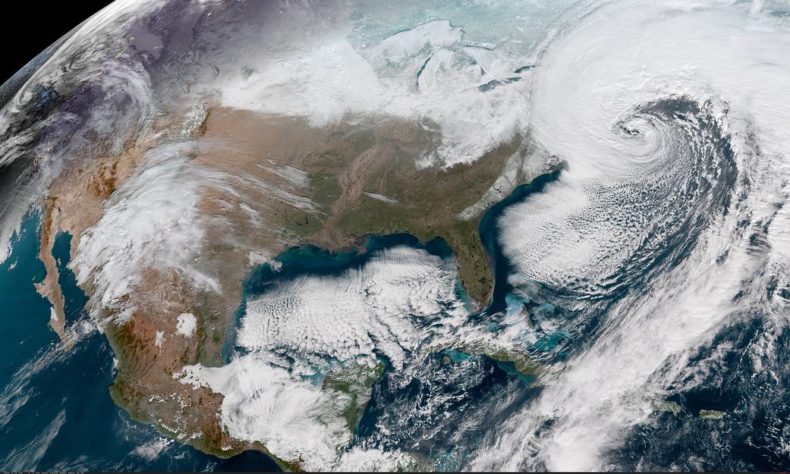

January 8-12, 2018 Last Friday night the Boston runway looked like an Arctic landing, bits of tarmac barely visible through sheets of blowing snow. I had a good view of the runway with the plane tipping like a seesaw, coming in on the tail of an

Last Friday night the Boston runway looked like an Arctic landing, bits of tarmac barely visible through sheets of blowing snow. I had a good view of the runway with the plane tipping like a seesaw, coming in on the tail of an