After several thousand years spent looking up and contemplating the nature of the cosmos, as well as what’s for dinner, we humans have amassed a lot of knowledge. We know the precise age of the Earth and the universe. We know how life sends copies of itself into the future. We know, with amazing accuracy, how strange mistakes in those copies lead to endless forms of life. We know who won the 1998 World Series and how to calculate area and the best way to make a beef bourginon. This is a lot of information to have in one brain, so humans also invented a way to offload some of that information and store it someplace else, through writing.

After several thousand years spent looking up and contemplating the nature of the cosmos, as well as what’s for dinner, we humans have amassed a lot of knowledge. We know the precise age of the Earth and the universe. We know how life sends copies of itself into the future. We know, with amazing accuracy, how strange mistakes in those copies lead to endless forms of life. We know who won the 1998 World Series and how to calculate area and the best way to make a beef bourginon. This is a lot of information to have in one brain, so humans also invented a way to offload some of that information and store it someplace else, through writing.

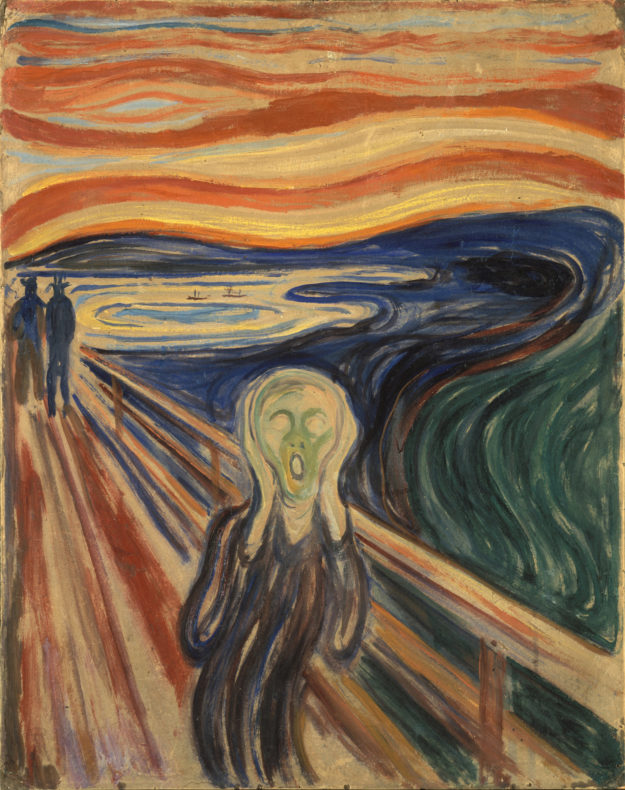

The loss of collective knowledge, either through deliberate acts of destruction or via accidents, remains one of the most potent sources of psychic pain — at least on a humanistic level. So there was something so touching about the press release I got from Astrobotic Technologies this week. Continue reading

The inhabitants of little world evolve very quickly, making them nimble in the Anthropocene. That’s good, because most things on Earth are little.

The inhabitants of little world evolve very quickly, making them nimble in the Anthropocene. That’s good, because most things on Earth are little.

It started with the maggots. One hot Australian January morning, unlucky beachcombers had discovered

It started with the maggots. One hot Australian January morning, unlucky beachcombers had discovered