A friend, author Ginger Strand, recently took this picture of a handprint I spray-painted on a wall in Manhattan. When I put it up a few years ago, the wall was blank, and she wanted me to know that graffiti has bloomed around it, along with this sweet little cluster of stars somebody put there (how I love you, whomever you are). On Thanksgiving, when in school we used to trace our hands onto construction paper and turn them into turkeys, I thought this would be a fitting post. The post originally went up in the winter of 2016.

Rounding a corner in Manhattan, I saw a handprint spray-painted on a wall. It was my hand. I had put it there last summer, my first and only piece of graffiti. It was nothing special, no artistic flair other than my five fingers. I had gloved my hand in plastic wrap and waved spray paint over it, creating a simple stencil out of part of my body, one of the oldest forms of enduring human expression.

The wall of the building had originally been a sprawling gallery of graffiti until, against the wishes of those living inside, the city whitewashed the whole thing. I was staying with one of the residents when the white-washing occurred. She invited me to go to the wall and plant a new seed. She was hoping graffiti artists would soon return and start the process again. A print was needed to kick off the next wave.

The oldest known rock art of a handprint was recently dated at 39,900 years ago in a cave on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi. The technique was more or less the same as mine. Wet pigment had been blown across and hand pressed against the rock to leave a negative impression.

Is there anything more indelible and primally human than the image of a handprint? The oldest print in the cave on Sulawesi is part of 12 prints painted at different times around images of animals. What was on their minds is hard to say, but it is a sentiment that is seen around the world. Other Paleolithic stencils of hands have been found throughout caves in Southern France, the oldest in Chauvet Cave dating to 31,000 years ago. El Castillo Cave in Spain has handprint stencils in red ochre dating to 37,300 years ago. From Indonesia to Europe, give or take 10,000 years, people were leaving the same expression. Continue reading

It has been said that penguins appear to be wearing tuxedos—crisp and elegant in their blacks and whites. This is not so of Humboldt penguins. If Humboldt penguins are wearing tuxedos, then they have been wearing them to jump trains for a couple of weeks, sleeping atop coal slag or down in the dingy corners of yawning boxcars. The birds are gray and ragged around the edges, their white chests flecked as if with cinder burns. And their eyes look like the last edge of a hangover receding—bloodshot, merry, curious. They look like they have seen some things.

It has been said that penguins appear to be wearing tuxedos—crisp and elegant in their blacks and whites. This is not so of Humboldt penguins. If Humboldt penguins are wearing tuxedos, then they have been wearing them to jump trains for a couple of weeks, sleeping atop coal slag or down in the dingy corners of yawning boxcars. The birds are gray and ragged around the edges, their white chests flecked as if with cinder burns. And their eyes look like the last edge of a hangover receding—bloodshot, merry, curious. They look like they have seen some things. “If this was a democracy, you would still lose,” is something my husband has told our 3-year-old after she objects to our decisions. I can feel the frustration build in her as though it were tightening my own chest. But in the world of Mary Poppins, she doesn’t have to take that kind of adult treatment. In that world, authority figures seem strict, but they are actually magical beings who provide weird and happy experiences, usually including animals. In that world, a kid can clean up her room by sheer magic!

“If this was a democracy, you would still lose,” is something my husband has told our 3-year-old after she objects to our decisions. I can feel the frustration build in her as though it were tightening my own chest. But in the world of Mary Poppins, she doesn’t have to take that kind of adult treatment. In that world, authority figures seem strict, but they are actually magical beings who provide weird and happy experiences, usually including animals. In that world, a kid can clean up her room by sheer magic!

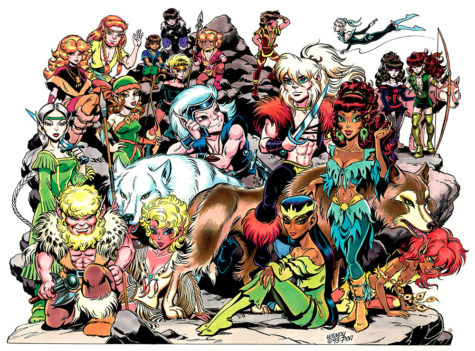

I first saw the elves on the floor of my best friend’s station wagon when I was seven. Grinning up from the back of a big book, these elves looked different from any other elves I’d seen. I’d always thought elves were a little wimpy, but instead of being fragile fey, these elves seemed fun. Even better–they had wolves!

I first saw the elves on the floor of my best friend’s station wagon when I was seven. Grinning up from the back of a big book, these elves looked different from any other elves I’d seen. I’d always thought elves were a little wimpy, but instead of being fragile fey, these elves seemed fun. Even better–they had wolves!