Are we making tactical nuclear weapons again? Tactical meaning “not strategic,” that is, not ones that take out cities and countries, just little ones that take out city blocks? So that we can get the jump on the the Russians before they can get the jump on us? Thereby invoking what the late, great Sid Drell called “the fallacy of the last move,” referring to one of the dumbest thoughts ever to occur to a dumb humankind? This post first ran May 30, 2013.

About ten years ago, doing research for a book, I asked Freeman Dyson about a study he’d helped do about whether we would have lost the war in Vietnam a little less if we’d used tactical nuclear weapons.

Dyson and two colleagues, all members of a scientific advisory group called Jason, were doing this study back in the mid-1960’s, more or less on their own hook; no one had asked either them or Jason to do it. They did it anyway because they’d overheard a Pentagon power honcho remark off-hand that it might be a good idea to throw in a nuke once in a while just to keep the North Vietnamese guessing. The remark reflected loose talk at the time that the few nukes dropped on mountain passes might block the passes and stop the enemy army from coming south. “You can do that wonderfully well with a few bombs,” Dyson said. “You blow down all the trees.” And I thought, “How does he know that?”

It turns out that while tactical (i.e., little) nuclear bombs do blow down trees wonderfully well, the large enemy army only has to clear a path through the blown-down trees and keep moving south. “It’s only bought you a couple of months,” Dyson said. “And you can’t blow down the same trees twice. After you’ve blown them down, that’s it.” He was snickering. I didn’t bother asking him how he knew this and didn’t think about it again until a couple of weeks ago.

I was interviewing another scientist who started digressing into the old nuclear bomb tests out in Nevada. “Tree blowdown was experimental,” he said, meaning they knew how nuclear bombs blew down trees because they’d done it.

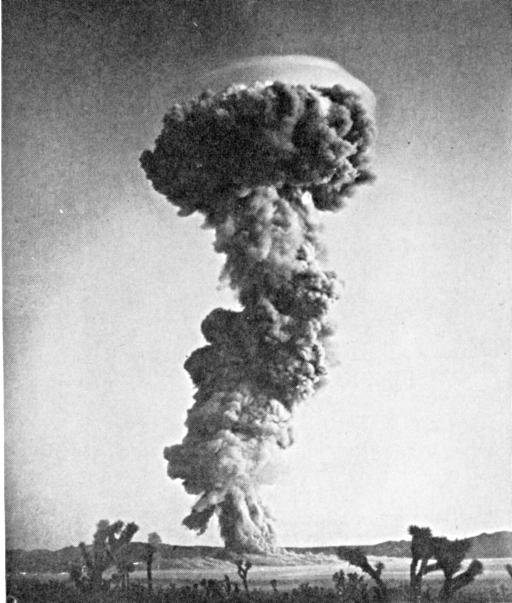

Once the U.S. had built the first atomic bomb, 1945; then improved it by building the first hydrogen bomb, 1952; then began working on building more portable bombs. And since the U.S.S.R had been doing the same, the U.S. also wondered about the bombs’ effects. So in the early 1950’s, the government set up models of all the things that bombs could blow up – houses, bridges, cars, pigs, sheep – and exploded bombs near them. The government did this for at least a decade and didn’t stop it until it and the rest of the world banned above-ground testing. The tests, many of them at the Nevada Test site, were called “shots,” and they had names.

The shot called Encore was on May 8, 1953 and among the many effects it tested was what a nuclear bomb would do to a forest. The Nevada Test Site wasn’t replete with forests so the U.S. Forest Service brought 145 ponderosa pines from a nearby canyon, and cemented them into holes lined up in tidy rows in an area called Frenchman Flat, 6,500 feet from ground zero. Then the Department of Defense air-dropped a 27 kiloton bomb that exploded 2,423 feet above the model forest. The heat set fire to the forest, then the blast wave blew down the trees and put out some fires and started others. Here’s the video.

I’m not sure what I make of this. Certainly in the 1950’s, nobody was controlling nuclear weapons; they were alive, reproducing, and roaming the world. So knowing precisely what damage they cause might help mitigate that damage. And certainly I’m not going to think about the more distant and longer-term effects of those shots, over 200 of them above ground, except to say that as a 10-year old girl in Illinois, I wasn’t safe.

I do know I’m impressed by the amount of directed effort, the thoroughness of thought that went into cutting down 145 ponderosa pines, trucking them out of the canyon, digging holes, filling the holes with concrete, sticking the trees into them, dropping the bomb, making the measurements, recording the whole thing. And though the United Nations belatedly began negotiating a ban on above-ground tests in 1955, the Limited Test Ban Treaty didn’t get signed until 1963. That was the limited treaty; the comprehensive one banning all tests everywhere took another 40+ years, and even now the United States hasn’t ratified* it. I’m most impressed by the contrast between the pointed determination of the test shots, and the infinite dithering about the (yes, infinitely more complicated) test bans. I might suspect that human nature and its governments have a dark side.

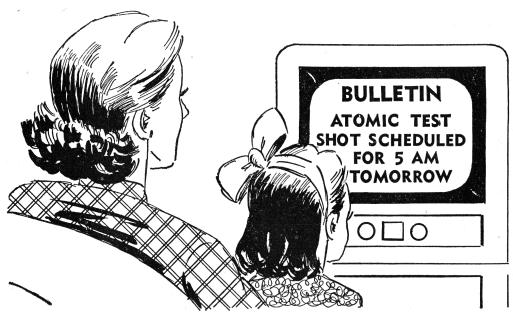

Add in this little public service booklet, illustrated with the drawing above and written by the Atomic Energy Commission to the people of Nevada: “You are in a very real sense active participants in the Nation’s atomic test program. . . . Some of you have been inconvenienced by our test operations. At times some of you have been exposed to potential risk from flash, blast, or fall-out. You have accepted the inconvenience or the risk without fuss, without alarm, and without panic. Your cooperation has helped achieve an unusual record of safety.”

As though they were asked.

____________

*UPDATE: In the original post, this word was “signed.” As noted in the comments by someone who ought to know, the U.S. did in fact sign the CTBT, but we still haven’t ratified it.

____________

Photo credits: Encore shot and drawing both from Atomic Test Effects in the Nevada Test Site Region which also includes the sentence, “Nevada tests have helped us come a long way in a few, short years and have been a vital factor in maintaining the peace of the world.”