The last time I saw Dyson, maybe six months ago, I wondered whether he might be slowing down a little; on the other hand it was a Friday night at dinnertime, when all natural creatures slow down a little. This post first appeared October 7, 2013; it’s been updated here and there.

I do seem to keep referring to Freeman Dyson, even writing whole posts about him. The reason, I think, is that I want to write a profile of him, even though 1) profiles of him have been done and done and done, the most recent being a full-blown biography; and 2) he’s way above my pay grade. The closest I can come to describing him is to say that he’s not like anyone I’ve met before.

When he’d turned 90, his long-time home, the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, gave him the kind of party scientists give each other: a day of talks on the subject on which the scientist has spent his/her life – like, say, low-mass stars. For Dyson, the Institute needed two days and four different subjects and even then I don’t know how they narrowed it down.

They called it Dreams of Earth and Sky*, and like Dyson himself, the talks were faintly contrarian. The first day they did physics and math. Dyson’s most important contribution to physics was a long time ago but it was fundamental: he reconciled two disjoint views of quantum mechanics. None of the physics talks were on quantum mechanics; one was on chemistry, another on climate change. Of Dyson’s math, I understand not one particle iota bit but one physicist told a Dyson-math story, variants of which I’ve heard many times: as a PhD student, the physicist needed a mathematical proof for his dissertation, he couldn’t figure it out, neither could his adviser, they decided to do without. Dyson was on his examination committee, said nothing about the missing proof and passed him; and afterward handed him a piece of paper with the proof written on it.

The second day was astronomy and public policy. The astronomers talked about the search for habitable planets and the requirements for the evolution of life on Mars. Britain’s Astronomer Royal — Martin Rees, Baron Rees of Ludlow – explained that the multiverse needs gravity, a departure from thermal equilibrium, a balance between matter and anti-matter, and at least one star. The policy people talked about whether taking the world’s nuclear weapons down to zero was illogical, how we can solve our energy problems with unusually innovative technologies, and how to apply a math game called the Bandit Problem to the ethics of clinical trials.

All these talks — technical and scientific, full of equations — were right up Dyson’s alley. He’s contributed to and written about all these fields. I suspect he was the only person in the audience of educated and intelligent people who understood all of them.

§

Dyson’s older sister, Alice, remembers him as a little boy, sitting surrounded by encyclopedias and sheets of paper on which he was calculating things. He grew up to be deeply humane, sharply aware of other people, and always curious about them.

§

Dyson talks about his family a lot, his wife and his six kids. I was walking across the Institute’s campus with him once and he was telling me about his son, George, and George’s book on Project Orion, and George’s book on Darwin. George had been a difficult child and rebelled against his parents, their life in Princeton, and Princeton itself, and had to get away. He went across the continent somewhere and became a boat builder. But he’d since come back and in fact, was temporarily at the Institute to research his fourth book, on computers. “George is here now, you know, at the Institute, my colleague now,” Dyson was telling me. “It’s such a delight, to be colleagues with him.” George has no patience with the intellectual life, Dyson said, and likes things concrete and real. “George builds boats with his own hands,” he said, and said again, “and now he’s here for a year, he’s my colleague. It’s so wonderful.” We turned down a brick path and there walking toward us was a taller, more robust version of Dyson. “Oh, it’s George!” said Dyson. He lit up like Christmas, he looked like the morning of the world. “It’s my son, George!”

§

Werner Heisenberg was great quantum physicist who worked on a nuclear reactor for the Nazis, failed because he calculated the critical mass wrong, and spent a lot of time thereafter in self-justification. I wrote in a comment to a post about Farm Hall that Heisenberg had three loyalties: 1) to himself and his reputation; 2) to theoretical physics; and 3) to pre-Nazi Germany. Dyson wrote back in an email that Heisenberg’s wartime letters to his wife, Elizabeth or Li, show that his first loyalty was to his family, to Li and their six children. Li was “a very strong woman,” Dyson wrote. “I remember when I met the Heisenbergs in Germany after the war, I thought, ‘There go MacBeth and Lady MacBeth.’”

§

I watched Dreams of Earth and Sky as a live stream on the computer. I was interrupted by an email from a friend saying that a 90-year old scientist we’d both interviewed and admired was in the hospital. “I know people can’t live forever,” she said, “but I’m selfishly hoping he’ll make it a few more years.”

Meanwhile, the live stream was continuing. At one point, a speaker wanted to hand something to Dyson from the stage but the stage was brightly lit and the audience where Dyson was sitting was dark. “I can’t see our honoree,” said the speaker. “Freeman, where are you?” Up from the dark shot a hand that waved and waved, silhouetted against the light: here I am <wave, wave> I’m right here <wave> I’m here.

___________

* If you want to know what the talks were really about, read Curious Wavefunction’s post. Not only was he there in person, he understood most of the talks. And he writes clearly. So yes, read it.

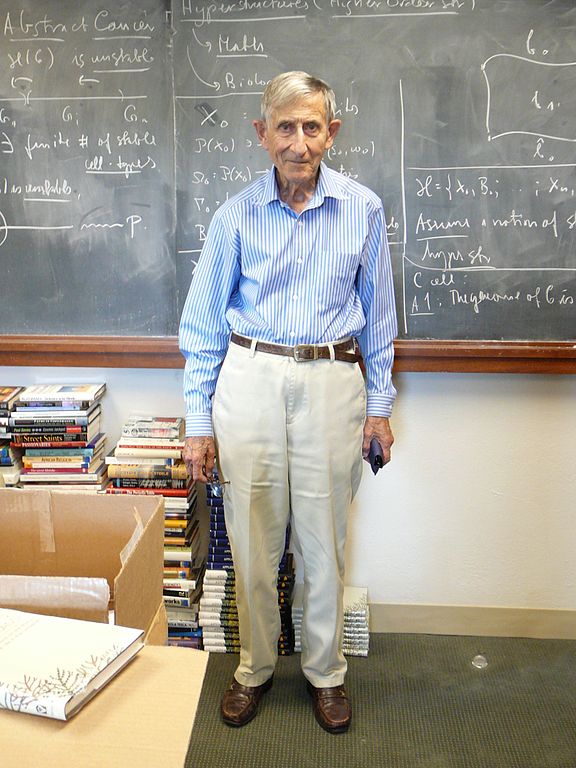

Photo credits: Dyson in his IAS office, 2007 – monroem, via Wikimedia

Not every juicy morsel works in every recipe. As a writer, I often come across something meaty, think, HUH! and then drag the link to a rarely visited desktop folder because, you know, I’m not writing a piece about using a dildo in zero gravity. (This time.) (Note to self: Pitch story on space-appropriate sex toys.)

Not every juicy morsel works in every recipe. As a writer, I often come across something meaty, think, HUH! and then drag the link to a rarely visited desktop folder because, you know, I’m not writing a piece about using a dildo in zero gravity. (This time.) (Note to self: Pitch story on space-appropriate sex toys.)