I haven’t heard the foxes for a good year now. The woods is still there but the owners sold it to a buyer who promised to cut down only the middle of it, you know how buyers promise things. No trees have been cut down yet but a lot of people have been tramping through the woods, measuring and discussing. Maybe the foxes got tired of the people, maybe they know what’s coming; but in any case, they probably got up and left. Not everything ends well.

This first ran September 8, 2016.

*

Across the street are two houses with two small yards, connected so they look like one, shaded by trees, one of which has a rope looped in it. The little kids come out of both houses, run through the shade into the dapple-spots of sunlight, disappear back into the shade, grab the rope and swing, climb up into the tree and perch like little panthers. Sometimes they sing. And one twilight, running into and out of the light, what they sang was “What does the fox say?”

The song was popular a few years ago but I’d never listened to it. I went inside and googled it. It’s an unsettlingly weird song by a Norwegian — what is it with those far northerners and their pale skins and light eyes and strange stories? The song is about a guy who knows that dogs say woof and elephants say toot but doesn’t know what the fox says; so a bunch of people dressed in animal costumes dancing in a woods tell him what the fox says, which is, among other things, Ring-ding-ding-ding-dingeringeding! Wa-pa-pa-pa-pa-pa-pow! Joff-tchoff-tchoffo-tchoffo-tchoff! You get the idea, they’re making it up, they don’t know what the fox says either. These sounds, coming out of the dark from kids in trees across the street, Fraka-kaka-kaka-kaka-kow!, were also unsettlingly weird.

I didn’t used to know what the fox said either. And that’s odd because I grew up on a small farm set in fields, backing on to woods. That’s prime fox territory. We kept chickens, and foxes would get into the chicken house and kill them. I knew it was foxes because my mother said so. But I never heard a fox.

So decades later, hundreds of miles away, in a city, I woke up one night hearing an unholy scream. It didn’t sound human, it didn’t even sound animal. I looked out the window and saw a large fox, long tail held out behind, walking slowly down the street, stopping every now and then to lift its head and scream. You have to hear that sound to believe it. It sounded like it came from a time before animals.

That was years ago; the fox lived in a woods behind the houses across the street. I now recognize the sound — it’s been called a vixen scream. Foxes live maybe five years, says Google, so that any foxes I hear now are probably its children. The neighbors keep track of them; on summer mornings they say, “Did you hear the fox last night?” For weeks they talked about one large one that limped; I never saw it. After a while no one saw a limping fox again so either the fox died or it stopped limping.

One night this summer, a neighbor and I were sitting on the porch as it got dark, talking about this and that. I was in the middle of saying something when she froze and nodded toward the street. There, walking down the middle, through the pools of street lights, was a fox and two cubs, maybe adolescents, all three sticking together. They might be heading toward the creek at the bottom of the street. They walked out of the dark, into the street lights, appearing, disappearing, reappearing, the way the little kids across the street moved in and out of the light. They slipped under cars, walked back into the street. Then they walked off into the dark, not saying a word, not saying any of the things that foxes say.

_________

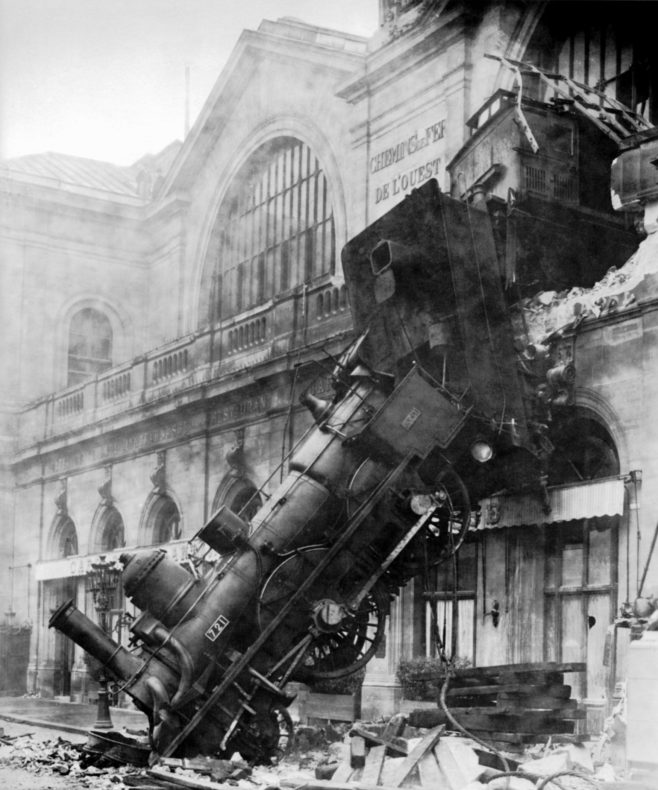

Photo by Oliver Truckle, via Flickr