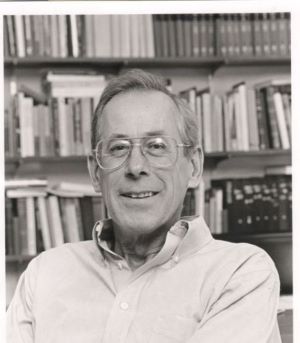

The following are excerpts from a profile of Jim Peebles, who just yesterday won a Nobel Prize. Peebles is a quintessential theorist — “I spent a few days standing near telescopes getting cold,” he said, “and in the end, my attention wandered” — whose opinion of his own theories is finely balanced.

The profile is old, from 1992, and from a magazine now dead, The Sciences. At the time I wrote it, the microwaves left over from the Big Bang had just been reliably measured for the first time, even though they’d been detected 27 years before by observers who didn’t know what they’d detected until Peebles told them. The observers went on to win the Nobel Prize; Peebles wasn’t mentioned. Should he have been? I asked, and he thought not: “Anyway,” he said, “I’m too young to be famous.” Apparently he’s old enough now.

In the informal basement cafeteria of the otherwise fancy faculty club at Princeton University, the physicist and cosmologist Philip James Edwin Peebles and three younger colleagues are having lunch over the latest hot news in cosmology. The lunch is fortuitous: one by one, the cosmologists have showed up a little after one o’clock and gravitated to the same table. Ruth Daly, David Spergel and Neil Turok are theorists, like Peebles, and among them the four have three theories about what went on in the early universe. The hot news comes from COBE, the Cosmic Background Explorer, a space probe that, for nearly three years, has been mapping a remnant of the birth of the universe, the big bang. . . . COBE has given theorists some badly needed constraints on how the early universe evolved. And so they debate: Whose theory of the early universe is still tenable?

Spergel and Turok are coming close to losing, but they are being gentlemen about it. Peebles is trying to convince the others that he is not losing. Daly, whose main interest is distant radio galaxies, remains uncommitted. As they talk, the four cosmologists become so intense, so serious that the outsider, who can barely follow what they say, can nonetheless see what they see: in the air just above the sandwiches, chips, fruit and juice, entire universes appear, evolve and disappear.

But, eventually, creating and modifying universes in thin air gets too hard even for the very smart, and Peebles resorts to the napkin under his plate, requests a pen and condenses the latest universe to graphs on the napkin. In the end, having pushed chairs back and put trays away, Daly, Spergel and Turok look thoughtful, and Peebles looks just a bit smug. The game has been fair throughout: although he is by far the most famous and senior of the four, he has taken up only a quarter of the conversation, and his convictions have been judged, as they should be, on merit alone. He is fierce and tenacious about his position, but he is unfailingly courteous about those of the others. He phrases his comments gently, as questions: “Doesn’t COBE specify that?” he asks. “And those fluctuations are on what scale?”

Continue reading →

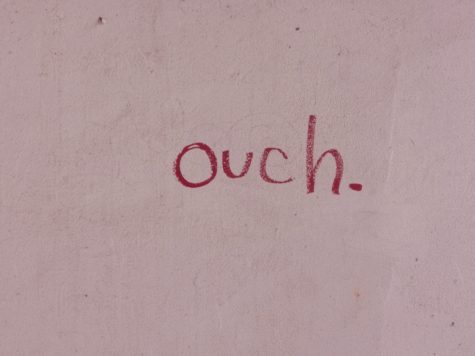

I’ve begun to wonder if, on one’s 50th birthday, a switch flips that loosens all that was tight and squeezes everything else in a vice grip. It seems that in the middle years basic gestures can cause lasting injuries. Bruises appear out of nowhere. My same-age friends and I compare aches and pains, and we all agree that our physical lives have lurched onto a new bone-jarring path.

I’ve begun to wonder if, on one’s 50th birthday, a switch flips that loosens all that was tight and squeezes everything else in a vice grip. It seems that in the middle years basic gestures can cause lasting injuries. Bruises appear out of nowhere. My same-age friends and I compare aches and pains, and we all agree that our physical lives have lurched onto a new bone-jarring path.