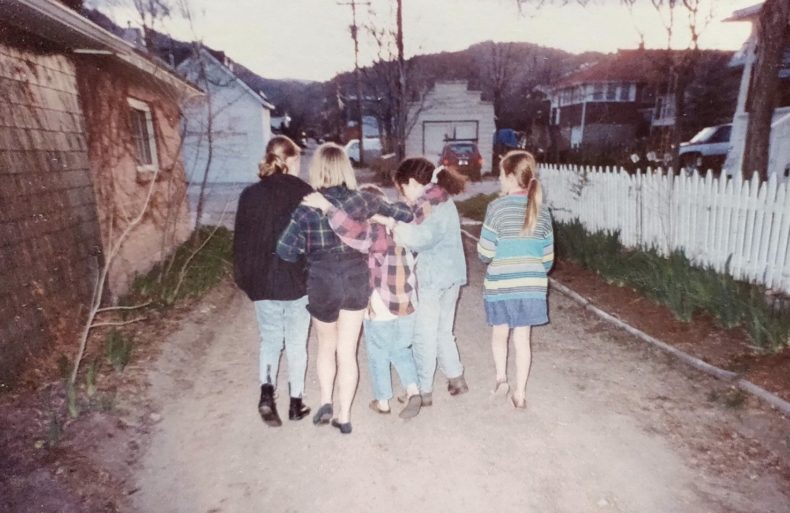

Do you remember when we used to yell at people from the roof? The light was longer then, and gold the way that it is in Colorado in fall, and we’d climb out your bedroom window and sit on the sloping awning over the porch and call out lines from movies to bewildered passersby. The lot of us were bony legs and arms lost in baggy clothes, then—members of a nameless generation that was not quite Gen-X and not quite Millennial. We were pre-internet and post-ennui, stringy haired and plaid shirted, sections of rope as belts, chipped nail polish and choker necklaces, pant cuffs frayed from slipping beneath our heels as we scuffed along sidewalks in combat boots or sneakers, our smiles marked with the metal trackways of braces.

None of us knew we were beautiful, then. We didn’t yet know how to love ourselves. But we were all in love with each other in that way that belongs only to teenage girls. Awestruck and skin-close, we drew on closet walls and each others’ arms, slept in down-lumped piles on the carpet when the VHS and whispering finally went quiet, slipped long notes into each others’ lockers, slipped into each others’ families. We were as tender as lovers, as vicious as sisters, knowing where the worst hurts lay, and prodding them when we needed to cover our own. We pushed aside our child selves, we tried to grow hard and sharp and cool and brilliant; we tried on things that the world insisted we should be, even as we fought to be something of our own.

Continue reading