“There is an aspect to this story that is weirder than you can

imagine.”

That sentence was e-mailed to me by a geologist, Jan Kramers, at the University of Johannesburg in the waning days of 2017. I had e-mailed him about a paper of his in Geochimica et Cosmochmica Acta. The title of the paper had caught my eye: “Petrography of the carbonaceous, diamond-bearing stone ‘Hypatia’ from southwest Egypt: A contribution to the debate on its origin.”

I think it was the name, “Hypatia.” It struck me as celestial, mysterious. Hypatia, I learned as I scrambled and stumbled by way through the paper’s dense geochemistry, is the name of pieces of what was once a single stone, found in southwest Egypt in 1996 by an Egyptian gem hunter and writer named Dr. Aly A. Barakat.

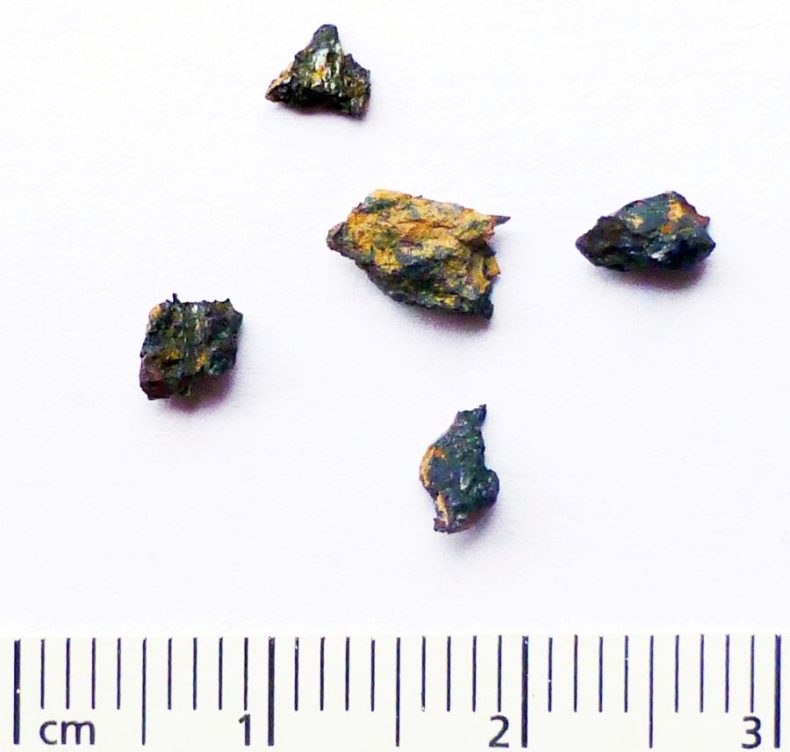

As stones go, it’s a strange one, although you wouldn’t tell by looking. Its fragments are drab, jagged, crumb-sized bits of rust-flecked gray. It was found in a nearly featureless, windswept desert and its mineral makeup didn’t match anything in the nearby geology, hinting that it might have landed there as a meteorite. Yet even for an extraterrestrial object, its makeup is unusual. It possesses enormous amounts of carbon and relatively little silicon, which is the reverse of what’s typically found in meteorites.

In 2013, Kramers and colleagues announced in Earth and Planetary Science Letters that it was actually a tiny piece of comet nucleus that had fallen to Earth some time long ago. Their 2017 paper revealed that much of its carbon was made of polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), the stuff interstellar dust is made of. The intense heat and pressure generated as this alien rock hurtled toward and hit the Egyptian desert transformed some of those PAHs into microdiamonds, forming a kind of sooty diamond crust around the stone that protected it from the withering desert until Barakat dug it up. The impact may also have been responsible for the numerous tiny, jewel-like pieces of glass strewn throughout western Egypt and eastern Libya known as Libyan desert glass.

The University of Johannesburg issued a press release accompanying the paper, which claimed Hypatia’s specific geochemical ratios suggested it predates the creation of our solar system, and that’s the headline that a few media outlets picked up on. But it was a throwaway mention in the paper, omitted from the press release, that intrigued me: “At the time of writing, the whereabouts of less than 4 g of Hypatia’s matter are known to us.”

So that’s why I first e-mailed Kramers in December 2017, asking where the rest of it had gone. He asked me to Skype him. When I did, he told me one of the craziest damn stories I’ve ever heard.

Continue reading →

Q: Can neutrinos travel faster than light?

Q: Can neutrinos travel faster than light?

Under institutional lighting, the chopped chicken in BBQ sauce is like oily pet food on a doughy white bun, and its juice runs into the glistening orange fruit from a can and the scoop of too-sweet slaw that nobody ordered. The woman across the table, Linda, who has a Scottish accent and is a low talker, admits she has “episodes” of not remembering, then she has one, right then, loses her train of thought while talking about losing her trains of thought. She is so tragically lonely. And there is Lynette, most of her teeth gone, Chicago Bears sweatshirt too tight and deeply stained. She has such a big smile, is chatty, loud, kind. She forks up the food, no qualms.

Under institutional lighting, the chopped chicken in BBQ sauce is like oily pet food on a doughy white bun, and its juice runs into the glistening orange fruit from a can and the scoop of too-sweet slaw that nobody ordered. The woman across the table, Linda, who has a Scottish accent and is a low talker, admits she has “episodes” of not remembering, then she has one, right then, loses her train of thought while talking about losing her trains of thought. She is so tragically lonely. And there is Lynette, most of her teeth gone, Chicago Bears sweatshirt too tight and deeply stained. She has such a big smile, is chatty, loud, kind. She forks up the food, no qualms.