On November 6, 2015, when this was originally published, I had just arrived back from the most bizarre trip my work has ever taken me on–and I’ve been on some pretty weird reporting expeditions. It was my first (and probably last) experience of being a royal guest in a place where royalty really runs the show. It was a week of berobed body guards with the hard stare of special forces, and hypermodern Beduin chic. But in the midst of it all were the 30 seconds described here:

I let the children have a go first and then reach out a recently hennaed hand, palm up, to accept the flannel armband from Mounir. The whole thing suddenly seems a little flimsy. Are birds supposed to wobble?

I’m a lot taller than those children, and my arm is accordingly further from the ground than the distance one would want a bird to fall. Do birds fall? Not generally, except as chicks from the nest, but this one is blindfolded, did I mention?

Because otherwise it would peck at my approaching hand with that beak I’ve just watched tearing through a plucked but still boned pigeon. Would a blindfolded falcon flap its wings if it lost its footing at dusk in the desert outside Abu Dhabi if there were a leather thingy covering its eyes?

Hang on, this isn’t a wobble, this is a lean. Those birdy legs are at an 80° angle to my arm, and the beak is correspondingly nearer to my shoulder, slash, head. Now it’s more like 75°. What’s happening, Mounir? This didn’t happen to the children. Get it off, I feel, but no, I think, I’ve been looking forward to this.

Continue reading

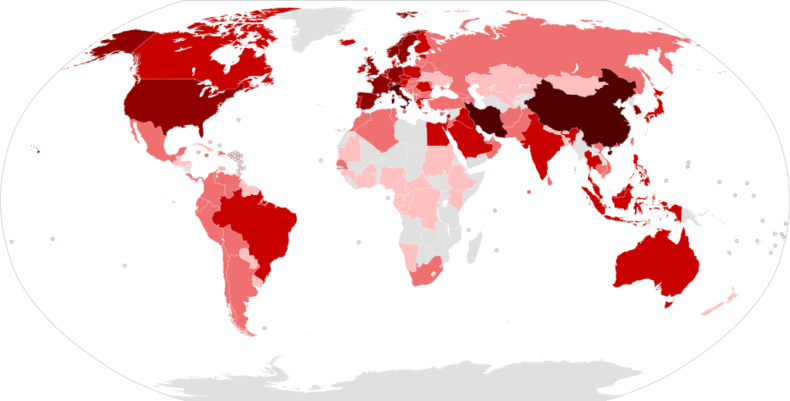

For the love of trees and their leafy kin, and with Australia’s horrendous fires on my mind, here’s a piece I wrote a few years ago about the surprising capabilities of plants that make their burning especially sad. Meanwhile, researchers continue to uncover remarkable details about plants’ lives, as in

For the love of trees and their leafy kin, and with Australia’s horrendous fires on my mind, here’s a piece I wrote a few years ago about the surprising capabilities of plants that make their burning especially sad. Meanwhile, researchers continue to uncover remarkable details about plants’ lives, as in