I’m sorry, I wrote this article about the biology of grief and I left things out. Which yes, articles always leave things out, they have to. But this particular omission bugged the readers and also bugged me: it was the length of time grief should take. The article said that after 6 to 12 months (different organizations have different numbers), if you’re not functioning better, you might have a case of complicated grief. This could sound like, if you’re still grieving 6 to 12 months after a death, you might need help. So first, what’s complicated grief? and second, what’s normal grief?

And third and most important, WHAT THE ABSOLUTE HELL? At 6 to 12 months after someone you couldn’t afford to lose dies, you might have located the planet you live on now but that’s about it. You’re still trying to believe that this person you loved is gone, you’re in intense pain or you’re numb, you feel completely and utterly isolated, you don’t much care about any other person except maybe the people who still have spouses or parents or siblings or children and you hate and envy every single one of them, you don’t much care about life which is meaningless and you don’t necessarily want to die but you don’t care if you do, and the only thing you can imagine ever wanting again is for this person to not be dead, to come back, please, just come back. Come back.

This, according to researchers and in my experience, is normal grief. After 6 to 12 months, it’s still there; also at 4 years and 10 years and 35 years. But it eases, it lightens, it changes and/or your relationship with it changes, and this is normal too. Then what’s complicated grief?

Complicated grief is a fairly recent focus of psychologists’ research. That research started out a century or more ago with Freud saying grievers needed to detach their love from the loved one who died and reinvest that love in something else, maybe a cat. (He couldn’t do it, though; when his daughter died, he was flattened and he didn’t get a cat.) Then the research moved on to detailing grief’s symptoms and timing how long they lasted; then started seeing stages in the grief; then noticed that the stages were unique to each person and happened in no special order and maybe never did happen, and in fact, might not be stages at all. Then research stopped worrying about how long grief takes and whether it happened in stages, and decided that maybe grief was a start-stop, on-off process that lasted as long as it lasted, and that during the process people were trying to figure out how to understand that this person they couldn’t lose was indeed gone and not coming back, and trying to figure out whether and how life could have joy and love and meaning again. Which sounds about right to me.

Then a group of researchers did something unusual for psychology: they found a bunch of random people; interviewed them and gave them psychological tests; and then for several years, followed their lives and kept testing them. In the meantime, some of these people, of course, had lost someone they loved. So the researchers could compare who those people were before this death with who they were after. I mean, sounds almost like science, doesn’t it. They found that, though grief is indisputably individual, grievers did fall into several patterns, the most common of which was resilience: going to work, doing laundry, going out with friends; bearing up under the pain as well as they can; figuring out where to place this dear, gone person in their lives now; figuring out how to love people again, how to feel joy, how to think again that their lives have meaning. I don’t actually need to explain that to you, do I.

Then maybe ten years ago another group, which included some of the smartest grief researchers around, found people who had been bereaved, interviewed them every six months for two years, and found the people who weren’t resilient. In the process, the researchers pretty much nailed the concept of a grief that had complications, though they called it prolonged grief, and maybe a better word would be persistent. And this is where the 6-to-12 months business comes in. The symptoms of grief don’t change character over time but they do soften and become less intense. And if, 6 to 12 months after the death, you’re still on Day One, then your grief might have complications, and you’re in the company of somewhere around seven to ten percent of bereaved people.

The reason psychological research focuses on complicated grief is that psychologists are in the business of helping people. Most bereaved people who might or might not walk into the psychologists’ offices don’t especially need help; they just have to keep doing what they’re doing. But people whose grief has complications might need help. After a year, they still can’t get back to work or or anything like regular life; they can’t get through their days which, every day, are full of pain. And psychologists whose job is to help people need a checklist: a list of symptoms, intense yearning plus, say, 5 of the maybe 8 symptoms that are intense, present every day, and keep you from living a life that, from the outside anyway, looks pretty normal. And if the helpers have a good, agreed-upon checklist, then they can make a diagnosis, complicated grief, and one day they’ll put it into the professional psychiatric manual of diagnoses, the DSM-V, and then hurray, insurance will reimburse expenses for its treatment.

So the part of my article that got omitted, the part that the commenters and I and even some researchers I talked to are still wound up about: compare that checklist with the symptoms of normal grieving in the second paragraph up there, and they’re exactly the same. The difference is in duration and intensity and the extent to which you’re flattened by them. It doesn’t go away, this thing. It gets predictable and increasingly avoidable; it’s gradually less surprising or dismaying. It’s just there, a thing you carry along beside you, inside you.

Not so different, you might think, from love. And what else would you expect? just because this person died, that love would just dissipate, float away, disappear like a fog? That’s not how love works. You already know that.

_________

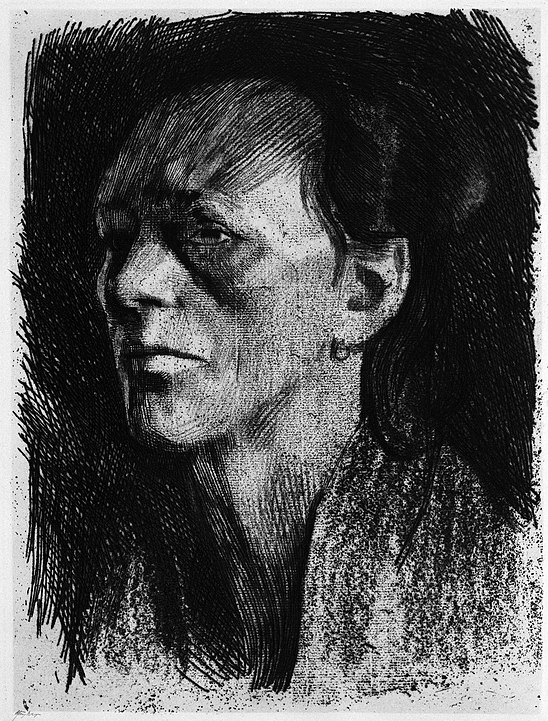

Käthe Kollwitz, Working Woman (with Earring), via Wikimedia Creative Commons

Truth.

Oh man Joann, you’d know.

I was talking about grief with an old friend just recently. He is an old friend in both senses. I’ve known him for nearly 20 years and he’s approaching his ninth decade. (Incidentally, he pegs his mental age at about 25-30 and I would definitely agree. He says that every time he sees himself in the mirror he gets a little shock at this old guy looking back at him. But I digress.)

We were talking about grief because of four deaths that have rocked my family over the last 5 months. Ages vary from 16 to 91. I mentioned how you never really “get over” the loss of someone dear, you just learn to live with it. He said something that resonated: “My first wife died 35 years ago. I still miss her.” He has been happily re-married for most of that time. This is not a contradiction. It’s just how love works.

Four deaths in 5 months, that’s terrible and you must be disoriented. And you’re certainly right, that’s how love works.

I shared counseling services with a client who requested “help” after the loss of her spouse of 15 years. She was certainly grieving the loss of a companion, shared interests, conversation, routines, idiosyncrasies, fond irritations. She sought help about 5 months after the loss. Her interest in initial sessions was to explore her pain and “now what am I going to do”. She admitted being concerned about how long it would take to recover from the loss. Ironically, the things she talked about most in session tended toward finding herself out of shape, experiencing muscle pain, aches and such, and loss of creative outlets. As she shared more about those areas of primary interest, her focus on “now what am I going to do” evolved to a focus on “now that”. That seemed to work for her. I will always remember her comment on the day she decided that she did not need to continue her life’s journey using a counselor: “I guess this took as long as I needed”.

Your client sounds classic, including the physical symptoms, and you sound like a patient and smart counselor.

Sometimes when I think about complicated grief, I remember this essay by Gregory Orr that begins with the fact that when he was 12 he held the rifle that killed his younger brother. How do we move from confusion, shame, and grief to hope, solace, and comfort? Here is what Orr says:

“As a young person, I found something to set against my growing sense of isolation and numbness: the making of poems.

When I write a poem, I process experience. I take what’s inside me — the raw, chaotic material of feeling or memory — and translate it into words and then shape those words into the rhythmical language we call a poem. This process brings me a kind of wild joy. Before I was powerless and passive in the face of my confusion, but now I am active: the powerful shaper of my experience. I am transforming it into a lucid meaning.

Because poems are meanings, even the saddest poem I write is proof that I want to survive. And therefore it represents an affirmation of life in all its complexities and contradictions.”

Full text: https://thisibelieve.org/essay/21249/

Thank you Ann for the lovely last paragraph. Continuing grief IS continuing love.

Oh hi, Inese! You’ll never guess how I keep track of you. I still think of your research with admiration. And thank you, thank you very much.