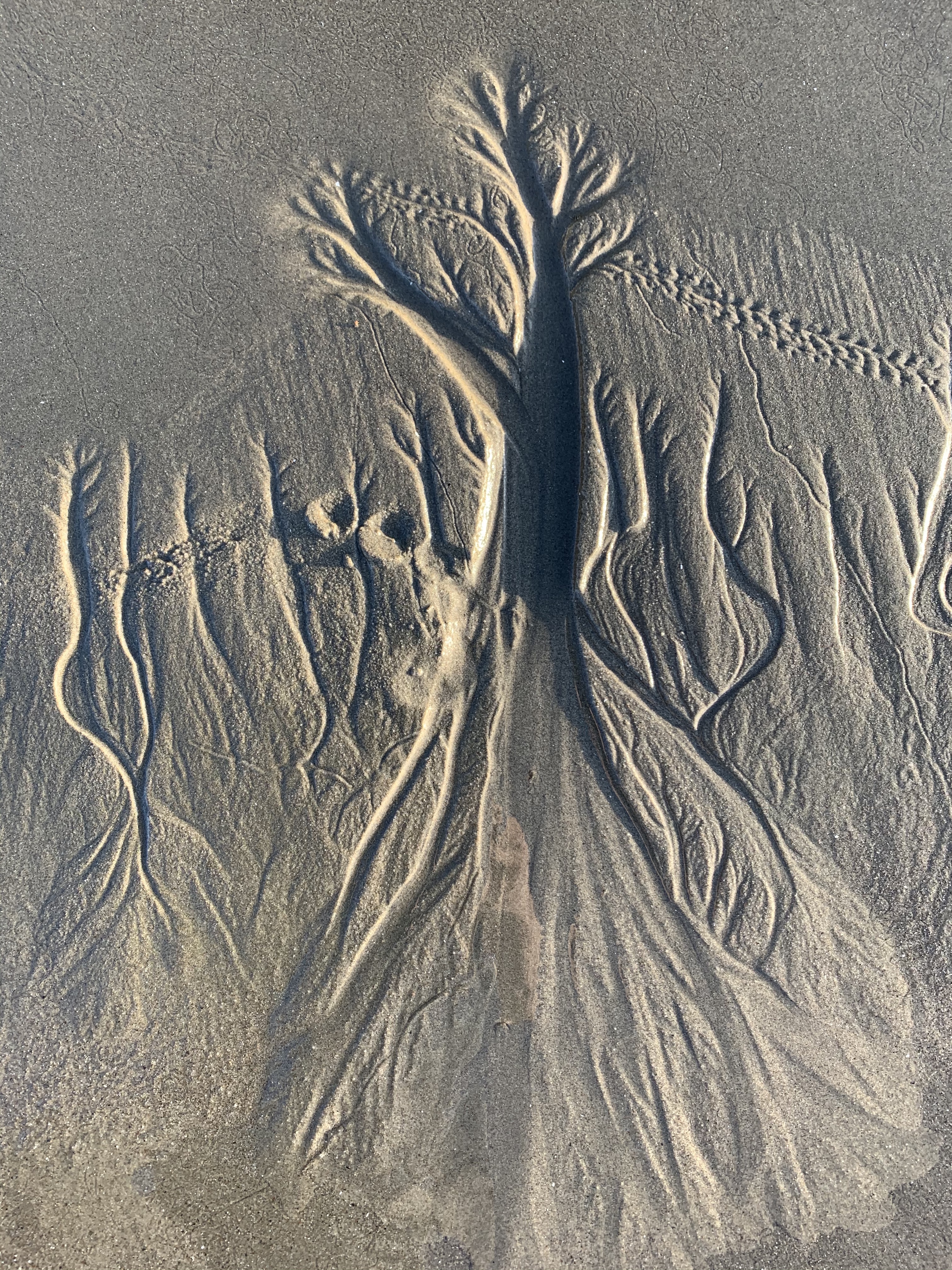

When I need to get out of my head, I go to Ellwood. This stretch of bluffs along the coast in western Goleta has trails through open grasslands and small paths that wind down to a wide beach, where you can find driftwood forts and views out to the Channel Islands. At its north end, a eucalyptus grove is home to winter roosts of monarchs. I have happy memories of wandering through the trees with a group of preschoolers in rainboots. When the sun broke through the clouds, dozens of the monarchs and their orange wings descended from the branches and hovered just out of reach. The grove felt, for a moment, touched by magic.

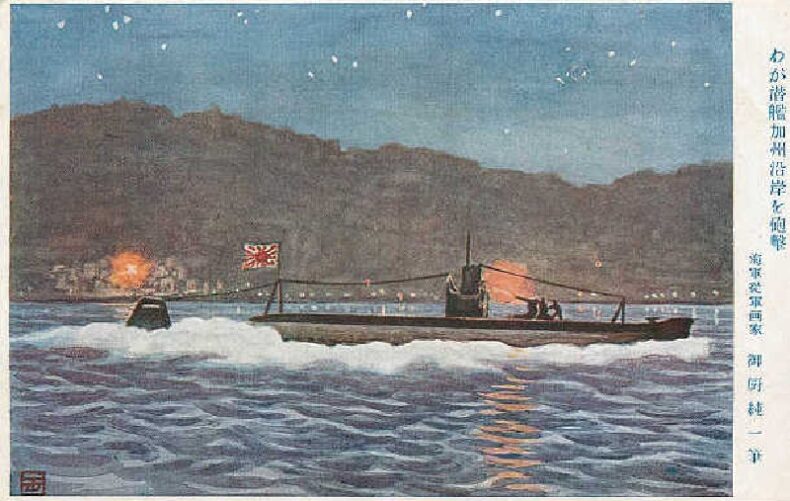

This is one of the things that makes it so hard for me to remember that right here, in 1942, shells from a Japanese submarine were the only thing flying overhead. After the attack, the Japanese Imperial Navy reported that they had “left Santa Barbara in flames.” This was wishful thinking: The damage, at least to the land, was minimal. The target, the Ellwood Oil Field, lost a derrick and a pump house. One of the shells crashed into a nearby pier.

But for those who lived on the coast and had just been listening to President Roosevelt’s fireside chat when the shelling started, the fear sparked by the attack was much more devastating.

One concern: Los Padres National Forest, just over the ridge. Many firefighters, along with the equipment they used, had been pulled away from this and other forests to fight in World War II. How could the Forest Service get everyday people more willing to stop the fires they no longer had the ability to fight?

The Ellwood bombardment was the sparkle in the eye from which Smokey Bear was born. Wearing a ranger hat and jeans, he’s urged generations of forest users to take responsibility for preventing fires from posters and advertising spots during Saturday morning cartoons, as a giant balloon during Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade.

But after decades of fire suppression—and increasingly devastating fires—some wonder if Smokey’s message could use an update.

One of these people is Emily Schlickman, a landscape architecture and environmental design professor at UC Davis. Every time she drove out of the mountains and back to the Central Valley, she saw a billboard with Smokey, still protecting the dense stands of forests that cover much of the Sierra Nevada.

Then, on a field visit to Illilouette Creek Basin in Yosemite, Schlickman saw something different. Instead of thick, protected forest or large stands of standing dead wood, the valley teemed with a patchy mix of meadows, grassland, and forests—the result of decades of allowing fire to burn through this area. “People say it’s like a glimpse into the past, like what a lot of the Sierra Nevada forests should look like today,” she says. She remembers turning to a colleague and saying, “What if Smokey had a buddy?”

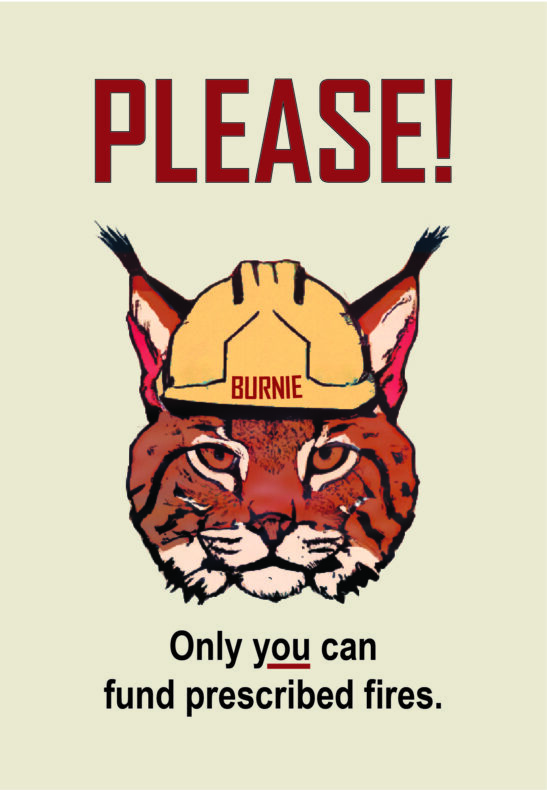

I found out about Schlickman and her work on my own drive out of the mountains. There was a billboard at the side of Interstate 80: ONLY YOU, it said in large white letters, CAN DECIDE OUR FIERY FUTURE. Next to the words was a pointy-eared bobcat in a hardhat.

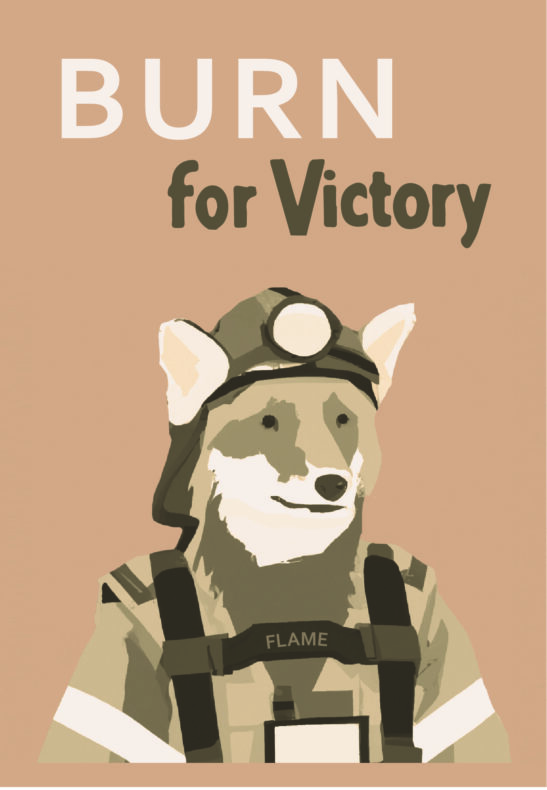

“Burnie the Bobcat” was one of several animals that Schlickman considered when looking at a mascot for a more nuanced approach to fire. Through her work in landscapes and, more recently, as a crew member during prescribed burns, she says, “I began to see the power, in many landscapes, of using fire as a beneficial force.” She started to look for creatures in California’s fire-prone ecosystems that have lived with fire, including tule elk, woodpeckers, and foxes.

Schlickman conducted a survey, and the bobcat was the favorite. This particular fire mascot also aligned with her desire to have a creature with widespread relevance. Bobcats live across the state, and across the country–although they generally avoid people and hunt at night. (One of the few times I’ve seen one in daylight was when I went into the brush to find a spot to pee—I wasn’t the only one watching the trail from the chaparral that day.) After a fire, bobcats take advantage of the exposed landscape in a fire scar to hunt for squirrels, rabbits, and rodents.

Burnie the Bobcat is the main spokesperson for considered fire, but Schlickman has other representatives, too, from Cinder the Coyote to Blaze the Bear, who she thinks of as Smokey’s sister.

Many of the animals representing the beneficial aspects of fire are female—just like many of the people on the prescribed and cultural burns that Schlickman participates in. “One thing I’m inspired by beneficial fire, is that so many amazing females are taking charge,” she says. “For so long, suppression has been guided by a really masculine, combative energy,” she says. “It’s such a relief to be on a prescribed fire or cultural fire”—a place where people talk about fire as a living thing—“because it’s a completely different take on fire.”

That’s not to say that all fires should be left to burn, or that there’s something wrong with the mild panic that rises in me when smoke starts to block out the sun. Usually, I feel relatively safe in the place we live—close to the coast, away from the narrow, winding mountain roads that have been threatened by fires here. But I also remember my hands sweating on the the wheel when my kids and I drove north in 2017, away from the approaching Thomas Fire, and the insistent buzz in my chest as we got stopped in traffic on the way, with a small fire burning at the side of the highway.

“Fire is scary,” Schlickman agrees, and not all landscapes benefit from frequent burning. Chaparral, for example, is burning much more frequently than its historic fire cycle, when 30 to 150 years might pass before an intense fire rolled through these scrubby, low-lying ecosystems along the state’s coasts and foothills.

But the way that people talk about fire matters, too. Researchers found that after the shelling at Ellwood, nearby newspapers increased the frequency of fear-related language and more conservative vocabulary–a shift that the researchers say lasted long after the war ended. Smokey has been around a long time, too. Maybe a shift is part of his future—with the help of a partner who can add a new perspective on fire fears. “There’s a lot of trauma in the state around fire, and I think it’s important to heal and understand that fire can be part of that healing process,” Schlickman says.

Now, walking along the Ellwood bluffs, there are only a few signs that anything ever happened here—a plaque in a golf course, a commemorative sign. Someone used the timbers from the broken pier to build a local restaurant. Each year, the monarchs return, their wings like small flames.

*

top image: Cameron Walker