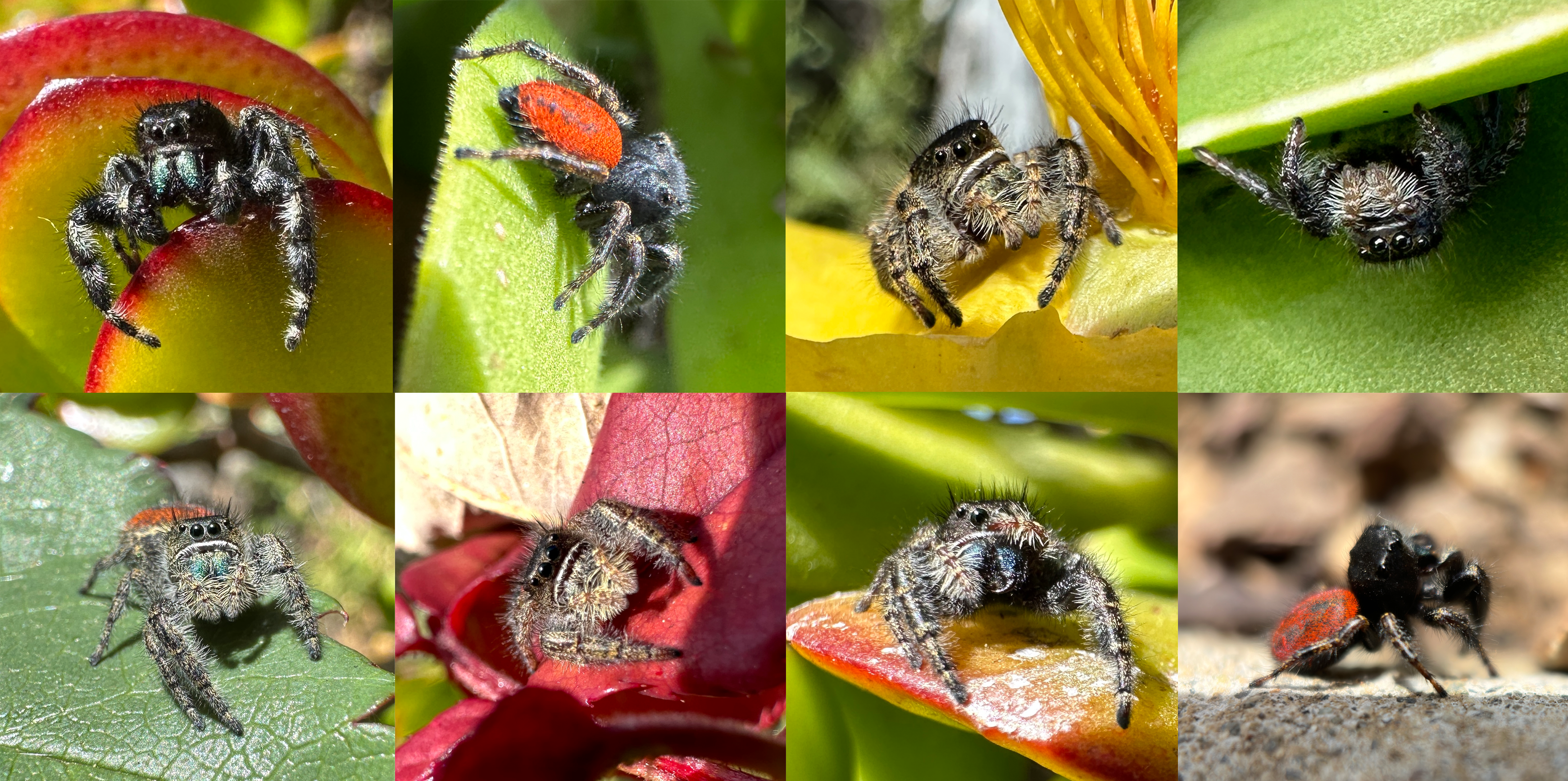

This is Diego. He is a Phidippus johnsoni jumping spider, and he lives on a jade plant in my front yard. There are several spiders of this species that can be found on the jade plant on any given day, but I know when it’s Diego I’ve spotted.

Adult males of this species are around 5 to 7 millimeters long, mostly black with bright red abdomens that often have a black stripe down the center, fuzzy black legs with white stripes, iridescent blue chelicerae (appendage-like mouthparts with fangs at their ends), and adorable little tufts of hair on the tops of their heads. Individual P. johnsoni spiders can vary in appearance quite a bit, but that’s not how I know it’s Diego.

It’s his personality that I recognize. Diego is a charming combination of cocky, concerned, and curious. But what really sets him apart is how he reacts to me slowly approaching, phone-first, to take a photo: He waves.

The first time he saw me coming, he quickly backed up to the edge of the jade leaf he was on, ready to disappear to the underside if need be. Once I stopped moving, my phone just inches from him, he hesitantly stepped forward, wiggling his pedipalps (fuzzy little arms that have many uses including cleaning eyes and sensing the environment), trying to assess what he was dealing with. It’s a spider’s way of asking, “What is that?”

Then he came closer, took a good look at the phone, raised up on tiptoes and threw his first pair of legs into the air. That was unexpected! He shuffled sideways back and forth while folding those legs up and down. It’s hard to explain how happy this made me.

I suspect he saw his reflection in the phone lenses and thought it was another spider. The leg-waving was probably either a warning to stay out of his neck of the jade plant, or a courtship dance. Either way this little routine was insanely cute.

I’ve encountered hundreds of Phidippus spiders in my neighborhood over the last couple of years, and photographed dozens of them with my phone. So far, Diego is the only one who responds this way.

Science has been slow to acknowledge that other animals have personalities, but anyone who has spent quality time with a dog or cat, a horse or pig knows that they are individuals with preferences, habits, and quirks, just as we are. The same holds true for non-mammals, but in my experience, it’s harder for humans, including scientists, to identify or accept personality in animals who are very different from us, like reptiles, fish, and insects.

Of course scientists have long been aware that individual animals behave differently from each other, but for a long time this was mostly treated as a problem when trying to draw conclusions about the behavior of a species. With some species, like fruit flies or zebrafish, this is easily overcome by testing a lot of animals. But with others, it can be challenging to capture, breed, care for, or get access to enough animals to keep the peculiarities of individuals from skewing our understanding of what’s typical for that species. A particular concern for scientists capturing their study animals from the wild is that they may end up with only the boldest animals who are less risk averse and therefore easier to catch.

It was only about two decades ago that researchers began seeing differences between individual animals as a topic worth studying for its own sake. But fear of being accused of anthropomorphism led scientists to take cover in the more rigorous sounding term “behavioral syndrome,” which was defined as a suite of correlated behaviors that persist over time and across different contexts.

The scientific literature is rife with this kind of recasting of behaviors and abilities that have traditionally been seen as exclusive to humans, using scientific-sounding words and phrases that describe the behavior rather than naming it. Friendship becomes “affiliative behavior,” laughter becomes “laugh-like vocalizations,” personality becomes “behavioral syndromes.”

But this is changing, and today animal behavior scientists are more likely to call animal personality what it is. I’ve been following this research for more than two decades, and I am no longer surprised when I see papers on the personalities of marmots, parrots, trout, or bees. Still, experiencing it myself with jumping spiders felt revelatory.

Last spring, while I was walking my dog Rooney, waiting for him to sniff every inch of an aeonium plant (those succulents with large green or purple rosettes), I noticed a Phidippus johnsoni spider on one of the broad, flat leaves. A couple houses later, I took a look at another green aeonium: another spider! I found several more on that walk.

The next day, Rooney and I walked by all those same plants, and again, most had spiders. I felt like I had cracked a secret code and now I could see Phidippus spiders whenever I wanted. I quickly identified the most reliable hangouts within walking distance of my house and I visit those spots almost every day.

I can tell exactly when the spiders notice my approach because they spin around to point their two big primary eyes my direction. Actually, some of them look at me; others disappear in a flash, ducking into the spaces between leaves. Some keep watching as I get closer but eventually lose their nerve and hide. Some like to peer out from behind a leaf. And some of them come closer, venturing out to the edge of the plant looking up at me the whole time. If I offer my hand as a higher perch, some will hop right on.

It didn’t take long to realize that certain spiders tend to react pretty much the same way every time I come around. I started to get to know them as individual beings with unique personalities.

This made these fuzzy Phidippus spiders even more irresistible. I usually can’t keep from trying to get a photo, and this brings out another array of reactions. Some spiders leap out of sight every time I slowly push my phone in their direction. Of those spiders, some eventually come back out to pose for photos, while others hide longer than Rooney is willing to wait. Some like to jump on the phone.

And Diego sometimes waves.

All photos credit/copyright Betsy Mason