This post first ran on January 7, 2014.

I am from nowhere.

Until my husband told me this — stated it as a fact, like “it’s raining” or “the sky is blue” — I’d never had a truthful answer to a question that has always given me pause: where are you from?

“You’re from nowhere,” Dave said. His words hit me like a punch in the gut. He’d meant it as a joke, a clever way of stating the obvious. To him, my lack of roots was a sterile fact. To me, it was a gnawing wound, a loneliness I could never shake.

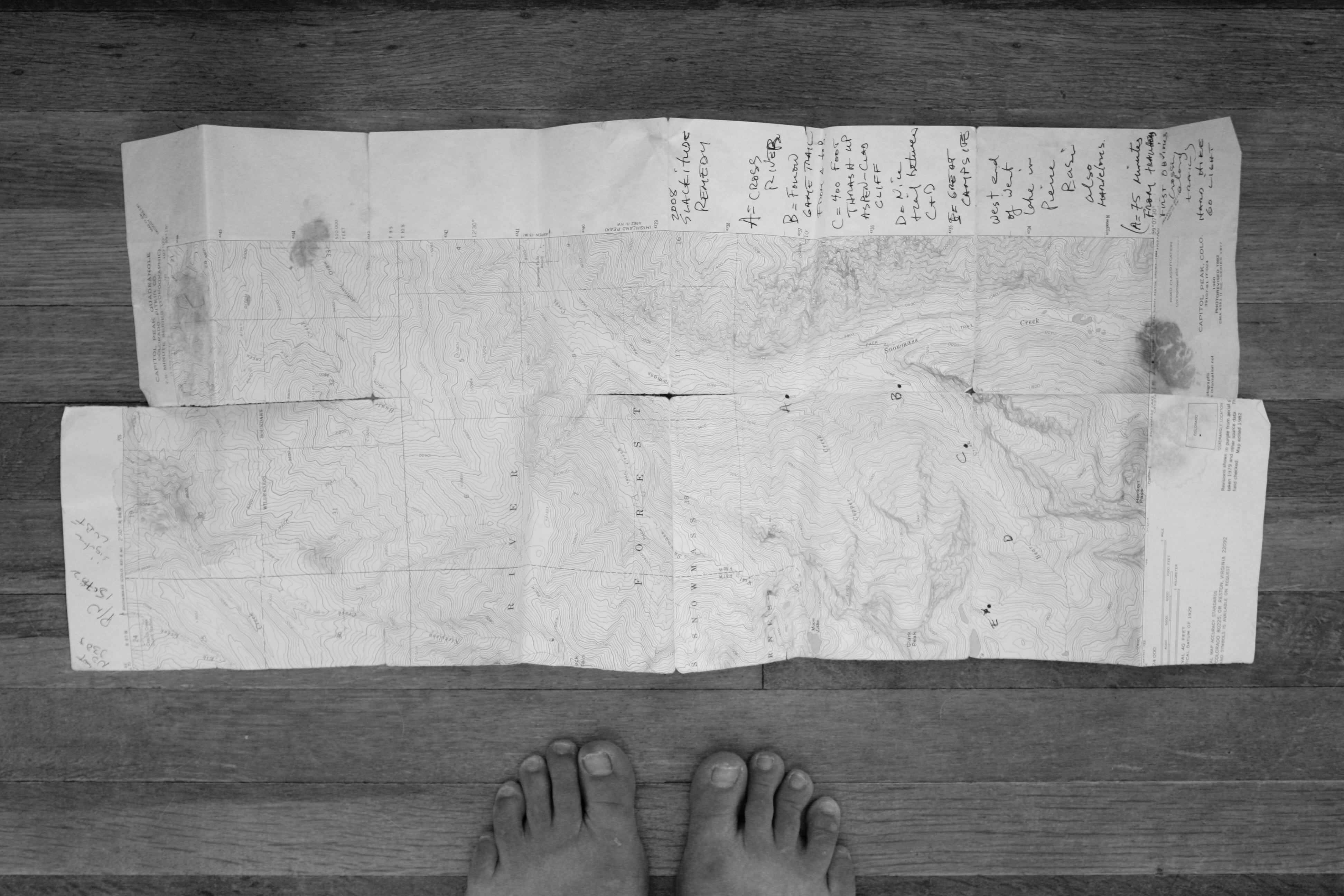

As an Air Force brat, I moved every few years. Before settling in Colorado, I had lived in three countries and more than a dozen towns. I was born in Texas, but we moved on before I formed a single memory of the place. My earliest recollection is of landing at a military base in Greenland and wondering who would give that name to such an icy place. I remember the swing set outside my kindergarten classroom near the Air Force Academy and the blue swimming pool in Phoenix that summer before we moved overseas, but the first place that feels anything like mine is a tiny village in West Germany—a town where I’m now a stranger, in a country that no longer exists. Continue reading

I keep a wooden box on my bedside table.

I keep a wooden box on my bedside table.