Before you read on, we are pleased and thrilled and absolutely overjoyed to introduce New Person of LWON, Eric Wagner! Eric is a fabulous writer and chaser of birds based in Seattle, Washington, who has written for the likes of The Atlantic, High Country News, Audubon, and Orion. He has penned magazine articles about techy fire lookouts who obsess over beet-influenced pee and watercolorists who dip their brushes in vodka. He once wrote an amazing book about the penguins of Argentina, and once more recently wrote an amazing book about Mount St. Helens, a truly obsession-worthy place if ever there was one. We love him and we’re glad he’s here. We hope you are, too!

One evening a week or so ago, I hiked out to camp on the eastern flanks of Mount St. Helens, in a place called the Plains of Abraham. The breeze was brisk when I arrived, the sky pink with a few tufts of cloud. I boiled some water for dinner and watched the mountain’s great shadow reach out for Mount Adams across thirty miles of unbroken forest. By the time I had licked the pot clean the sun was gone, so I got into my sleeping bag, zipping it tight until just my eyes and nose were exposed. A dazzling mass of stars dotted the cold, clear sky. Beneath them the mountain loomed, blacker than night. The conditions were perfect, I thought, for what I had come to do: end things, once and for all, with Mount St. Helens.

I first met the mountain, from a professional standpoint at least, a little more than six years ago. Tasked with writing a book about it, I was at an event called The Pulse. This was a regular gathering of scientists who worked at Mount St. Helens, some since the 1980 eruption. For a week I listened to a parade of -ologists—ecologists, geologists, hydrologists, others—all the while trying frantically to scribble their every word. When my cramped hand needed a break, I stepped away and looked with a growing sense of despair at the mountain. There it sat, massive and austere. Would I be able to learn even a small fraction of all there was to know about it? I had my doubts.

I was contractually obliged to try, though, and for the next few years I went to Mount St. Helens as often as I could, insinuating myself into the lives of the -ologists. Patiently they explained their research and what it showed about the mountain’s post-eruptive comings and goings, sharing as well their enthusiasm for the blast area as a landscape. That it was geologically and ecologically unique I understood well enough, but they talked about the peculiar hold Mount St. Helens had on them, its allure. One spoke of what he called his sacred places. These were spots scattered around the mountain where he had been gifted with particular insights into his questions. “Everyone has their own,” he told me.

The field seasons went by, and while I had a lot of fun trailing after the -ologists, the one thing I really grew to love was that, unlike other projects where I had been beholden to scientists for access, I could come to Mount St. Helens whenever I wanted. To learn about it from the -ologists was one thing, but I could approach it on my own, and in my own ways. I spent who knows how much time hiking all over the mountain, around it, climbing it, seeing it from up close and afar.

During those wanderings the Plains of Abraham became for me a sacred place. Odd, considering the effects of the 1980 eruption were minor there compared to the land and lakes to the north, where the bulk of the research effort lay. But that was why I liked the plains so much. More than the other Cascade volcanoes, Mount St. Helens has a public face and a familiar history: the crater, the blast and its aftermath. Lying to the east, the Plains of Abraham offered different consolations. The crater was nowhere to be seen, and the plains themselves were sere and stark, and apparently always had been, with just a few hardscrabble plants, the odd shrub. The main trail through them was just half a mile from the mountain, which seemed close enough to touch.

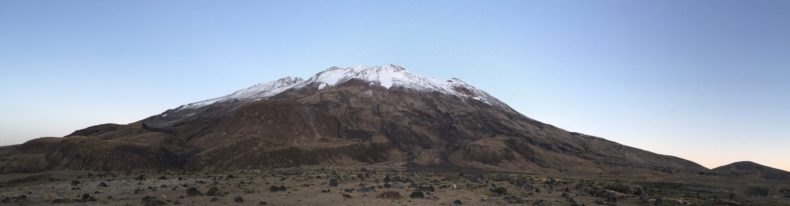

On my own I kept returning to the plains. They were a source of private superlatives, with the mountain as urtext. Once my daughter and I camped there, and she was so tired from the hike out that she slept right through the most awesome thunderstorm under which I’ve ever trembled. Another time, on the last morning of a long trip during which I got the worst blisters of my life, I woke on the plains at dawn. Dreading the miles to come, I hobbled out of my tent and looked up at Mount St. Helens. The surrounding sky was the sweetest, most delicate blue, and the prominence was softly illuminated as Mount Adams obscured the direct light of the rising sun. Every feature of the mountain, every rock and furrow and ridge and saddle and col, was in sharp focus, painted with a subtle palette of browns and grays, and dusted on top with the fall’s first snows.

“What is it with you and the Plains of Abraham?” one -ologist asked me later while I limped along after him, recounting the trip.

All I could do was shrug.

Anyway the book came and went. Afterwards there were certain spiritual difficulties. To write a book is to presume (or hope) that you will say something like the last word on the subject. But science is dynamic, and so of course the moment the book was published it felt obsolete. Some of the studies I’d spent so much time studying ended. New ones began. The landscape was changing, or being changed. The Mount St. Helens I had come to know was no longer, even as it still sat there, impassive as ever.

Humbled by geology, I struggled with being left behind. I didn’t know how hard it would be to reconcile myself to those most basic things: the passage of time and my own insignificance in the face of it. Where Mount St. Helens was concerned, perhaps I shouldn’t have been surprised. Several of the -ologists I had been following came in the early 1980s meaning to stay only for a few years or so. I understood now their sometimes rueful tone when, decades on, they described the durability of their attachment. One had said, “Mount St. Helens gives you a lot, but she takes a lot, too.”

Likewise, here I was needing to move on to new things, but I kept looking for or making up excuses to visit the mountain. Just a hike through the backcountry, just a couple of nights to help out with some project here or there, just this, just that. Just one more morning of magic on the Plains of Abraham. Then, I swore to myself (and my family), I would be sated forever.

When my eyes popped open a little before 6 a.m., the sun was bursting around Mount Adams, but its light was sandwiched between heavy clouds above and thick fog rising up from a valley below. Within minutes the fog crested the lip of a ridge and flowed into the plains, obscuring Mount St. Helens and everything else in a chilly wet mist. There would be no glorious final communion with the mountain for me. I couldn’t even tell where the sun was.

Oh well. Maybe next time. I was sure I could squeeze in another trip before the road closed for the winter.

I laid my gear out to dry as the breeze picked up and then drank a cup of coffee, had a slow breakfast. When I hiked out an hour or so later the fog was starting to lift. As I had so many times before I got out my phone and snapped a photo. Not too bad: Mount St. Helens, the sky, the retreating clouds. But, I thought as I walked on, a picture doesn’t begin to do this place justice. It would take a thousand words: to describe the bracing cold wind, the feel of it on my reddening hands, the sound of it in the shrubs, how it smelled so sweet and clean as rushed over the open ground to clear the clouds, the way it spurred me to walk faster to stay warm. Oh, I could go on and on. It would take something like a love letter, if not a book.

Photos by Eric Wagner

Welcome, Eric! In my mind, your “Portrait of a Marriage” will sit alongside Ursula Le Guin’s essay “A Very Warm Mountain.” Le Guin writes of looking out her study window to see the formerly “serene outline” erupt again and again. She says, “We cannot predict what she may or might or will do, now, or next, or for the rest of our lives, or ever. A threat: a terror: a fulfillment.” But she adds: “This is what serenity is built on.” And maybe the science writer’s life & work might also be full of the unforeseeable … for better or worse. I’m looking forward to reading more about where your curiousity and due diligence takes you.

Thanks for the kind words of welcome! I love the Le Guin essay, too.