When one of the founders of conservation biology passed this week at 84, I heard it was peaceful, that he was ready. I imagine Michael Soulé’s heart and breath stopping and an incredible release of feathers and bones, colors of a million beetles, a rush of eyes of countless shapes.

You might say he ushered us into the sixth mass extinction, old guard, one of the first scientists to coin the term ‘biodiversity’. He has seen us across the threshold, a former Earth becoming a new one.

Soulé once thought the natural world could be saved, then resigned himself to the fact that it wouldn’t be, that we would do the opposite. He gave up on the human race long ago, at least our ability to turn the tide, especially for the sake of charismatic beasts, the megafauna, big-boned, standing on the horizon like memories on their way out. He believed, and he’s probably right, that we are at the end of the age of the great animals. Polar bears, elephants, whales, and most other creatures exceeding a hundred pounds are fading. He sees them no longer having opportunities to speciate, no room to mix their genes. We’ve fragmented their ecosystems and undercut most of their habitats, greasing their path to extinction.

“It’s not death I mind,” he once said. “It’s the end of life that bothers me.”

Years ago Soulé said to me, “My optimism, a macabre form of optimism, is that the shit hits the fan a lot sooner than we think and forces us to wake up.” I asked if that would stop the Anthropocene from coming. He said, “You can’t stop it. It’s here. The Holocene is gone, the megafauna are gone. A majority of the large, wild creatures will survive only in zoos by 2050. Lions are disappearing from Africa, wolves and grizzlies from North America.”

I told him that I believed the Holocene wasn’t over yet, the geologic epoch not yet turned. He said I was entitled to my opinion.

I think he saw me as young and stupidly hopeful. I saw him as a regal and scientific god, and a friend. His was the generation that carried us into the flames of over population and massive habitat fragmentation, and I believe he was trying to atone for our empirical sins. He was a Zen buddhist by practice, as he’s said, to cope with his own competitive, anxious nature. I’ve wondered if it was a way of dealing with heartbreak.

Soulé was a cofounder of the Society for Conservation Biology and The Wildlands Project, an organization pressing for half of the U.S. to exist as wild. He never gave up hope. He found his greatest joy in all that is not human.

In an interview in The Sun, he said: “I was looking at the shells of land snails and wondering about their components. Where had that calcium traveled, and what shapes had it taken over the course of its geological history? It possibly had been in the bones of dinosaurs, in the teeth of mastodons, and now it was in these perfect, delicate shells cupped in my hand. That was another opening to a feeling that we’re all connected — in the paleontological as well as the spiritual sense. Are the two different? The feeling of connectedness was far more powerful than I can convey.”

He and I bantered for years over the future of the Earth and its species. I told him I could not let my heart break. I kept up hope. He looked at me with such gentleness, forgiveness, and relaxed, attentive wisdom. I don’t remember the exact words, but he said that my heart would have to break. There was no other way.

Born in 1936, Soulé went from a generation where the world would always be as it was, a cornucopia of species, to the hot, smoky outlook of today. He grew up around San Diego, exploring tide pools, desert, and mountains, a kid when the first atomic bomb went off in southern New Mexico. He witnessed a change few after him can grasp.

Soulé envisioned corridors of animal migrations reopened after we’d shut them down with the monumental rise of our species. The Rocky Mountains stretching from Canada to Mexico are where he saw the likeliest big conservation corridor, and he put his back into campaigns to make this happen, writing, “A step in this direction is to reconnect severed landscape arteries in order to restore vigor to wildlife…”

Here at the dawn of the sixth mass extinction, we understand there are no simple answers. Solutions seem beyond our immediate grasp, problems stacked so high they boggle the mind. You wonder if there’s room for loving nature anymore, or if a scientist like Soulé is anachronistic.

When the guard changes, you do not throw away what came before. The waste is too flagrant. Hold onto what works, what sees the world through. His is the science of connectivity. Everything relies on everything else. Life cannot be isolated. In order to survive and thrive, there must be space, interaction, association.

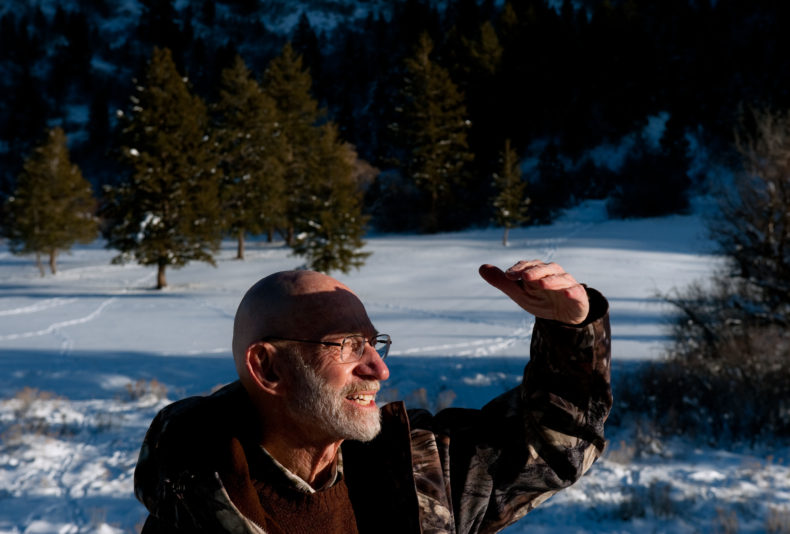

I once put a willing climate change denier on stage for a theater performance, and, as part of the show, had a spotlight land on Soulé in the audience. He stood and said he objected. In a circle of light, he pleaded for this planet, for all that is not human. I watched from behind the curtain, seeing the audience blacked out, the nearest faces dimly lit looking up at his bald, noble visage. He had the key. It was so simple. Stop devouring it all. Leave more for other species. Open the spaces, make them wild, let them connect with each other. Love the natural world. This is what carries through for me from his life.

Image courtesy JT Thomas Photography

Further reading on Michael Soulé from Michele Nijhuis for LWON:

Amen!

“He has seen us across the threshold, a former Earth becoming a new one.” What an unbearable message to deliver.

“I imagine Michael Soulé’s heart and breath stopping and an incredible release of feathers and bones, colors of a million beetles, a rush of eyes of countless shapes. ” This may be the most beautiful sentence you have ever written.

And, in this time when so many are in desperate need for elders, thank you for bringing him to us. I wonder if one of the hard gifts of being old is that one becomes able to bear the idea of devastation – and, therefore, able to cut through our distinctly America longing for everything to last forever.