Ten years ago on the Greenland Ice Sheet I sat at a circular table in the cook tent of a seven-person research station. Wind banged and thrummed outside. A storm had been on us for days. After going out to pee, you’d stomp back inside sequined with the frozen glitter of your own urine. Around the table talking climate change were a couple NASA scientists and a small team led by Konrad Steffen, one of the lead cryosphere authors for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

There was also a climate change chaos researcher named José Rial from University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He’d been planting microphones on the ice, listening for bubbles and quakes, trying to determine patterns in what other scientists dismiss as noise. While the others talked at the table, Rial remained buried in his laptop.

The wind hit the tent like a crashing sea, sometimes overwhelming the conversation, which was about our steadily warming climate. A young French snow researcher got worked up, cursing at how we’re pushing this planet into the hot zone. Rial, in his 60s, the camp elder, said nothing.

Rial’s studies were in turbulence and complex systems, searching for a key not just to the planet, but to all chaotic equations. A regal man, like I imagine Neruda, with some swaggering trickster to him, he would slip into orations out of nowhere and was ready with a crude joke, grinning almost imperceptibly as you figured out the punchline.

This chaos scientist and I had been first to arrive, opening the camp for the season, and on the flight out — crossing onto six and a half thousand square miles of ice and snow — he looked through his oval window and declared, “As Darwin said, so much beauty for so little purpose.”

The plane dropped us at Swiss Camp, a huddle of two red Quonset tents that had been weathering the winter without anyone home. Rial and I unloaded about a thousand pounds of gear and the plane took off in a swirl of snow, leaving us with crates, propane bottles, and a frighteningly sweet sense of desolation and aloneness. That’s when Rial noticed camp had been badly damaged. Parts of snowmobiles stuck up at odd angles, weather stations destroyed. Storms that winter had been some of the worst on record. Both tents were busted open, their insides crested with snow six feet deep. Rial dug a hole through the door of the cook tent and slithered in, boots last to go. When I poked in my head behind him, I saw a ghostly chamber of snowbanks and feathery stalactites hanging from the ceiling. I told Rial it looked like the structure was unsound, that outside supports were broken where they held the wood frame floor up off the ice. In response, he jumped up and down on the floor as hard as he could. The tent didn’t collapse. He seemed ok with that.

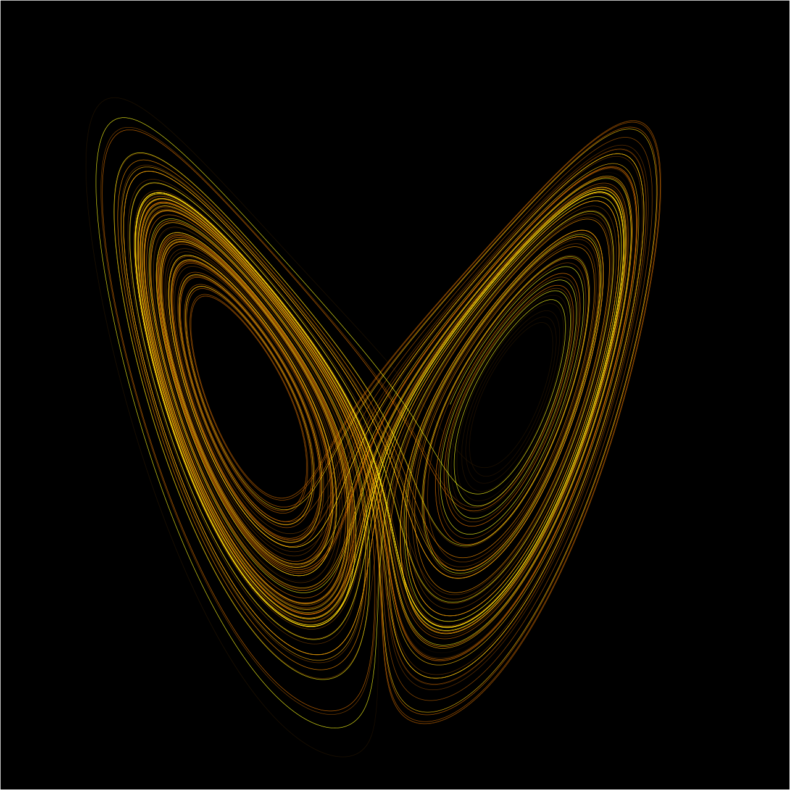

In chaos theory, when variables become too many, a system goes turbulent. It’s called the “accumulation point.” Laminar flow, if there ever was one, twists back and starts eating itself. This is the science of ouroboros, where the answer returns and changes the question, evolving into feedback and distortion. In that distortion, you look for a pattern, a blueprint forming, evidence of self organization. Decades ago, I wrote a thesis in college comparing Native American trickster mythology and chaos theory, finding they both say the same thing: shake up a dynamic system and it naturally resettles at a higher level of order, not where it used to be. In the scientific disciplines, heat is often what shakes things up. The hotter it gets, the more turbulent, the more chaotic. In Native American tales, trickster comes dancing in, throws everything into disarray, and by the time he leaves, stars have been scattered in the sky, or skunk has its stripes. A new order has been reached.

At the round table, revered and well-studied scientists agreed that an exhausted, overheated planet was in our future. There was no going back.

“Not necessarily,” Rial said as he looked up from his laptop. He said when a system as complex as global climate fluctuates as much as we’re seeing, it can jump any direction. When it lands on a new equilibrium, it might not be the one we expect.

“I think an ice age is coming,” he said, and went back to his laptop as if dropping his mic, ignoring the huff of disagreement from Steffen, the head glaciologist on the team.

Later, when I asked Rial, he said he’d been serious. At least if it’s a flip of a coin, which it might be, ice age is as likely as a greenhouse blanket. He had no doubt humans have a crucial hand in this, leading earth systems rapidly toward imbalance, but he also believed there are levels of climate interaction no models have taken into account, major variables not yet understood or even seen. In his Wave Propagation Lab at Chapel Hill, he and his team studied, “the synchronization of polar climates in search for simple rules at the heart of climate’s complexity.” He thought that climatic events on the Southern Hemisphere tell you what may happen next on the Northern Hemisphere, and vice versa. Extreme temperature variability in Greenland he found linked to the same in Antarctica, as if in direct response to each other. The two sides of our planet are communicating, influencing each other.

Rial’s comment at the table stuck with me. It was the simple fact of chaos theory: the planet is going to jump. The accumulation point seems to be loading up. One way or another, hotbox or glaciers, the system is changing.

That summer, after I left the camp, the ice melted around it. It had never melted that far onto the ice sheet. The camp had stood since the 90s, rising and falling on glacial waves as the ice flowed over a mountain range buried below. For the first time, it completely collapsed, falling into a splintered mess of gear and plasticized tent fabric. It doesn’t prove Rial right or wrong, just more grist for the mill.

Last year, Rial died. I occasionally think of our conversations on the ice. As current political, social, economic, and environmental systems around us flutter, jerk, and sometimes go up in flames, I turn to him, or his watchful ghost, and say, is this what you meant?

Rial says yes, a new system is being born. Every influence is now on the table. This is the delicate time, when effects are becoming nothing but feedback. Every nudge and bump changes the course. Do what you can, if you can, and watch the future remake itself.

Image: the Lorenz attractor/butterfly effect

Wisdom isn’t always self-evident

We can wish all we want for a magic renewal. We have killed off magic – and we are killing off each other and, worse yet, sentient life on our home planet. We meditate and pray and dream – and we go on doing the deadly behaviors that are our weapons against this earth. This warning was published i 1997: https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg15320692-500-science-aircraft-wreak-havoc-on-ozone-layer/

Hope for renewal is the luxury of the fortunate. Fury and action are the tools of the deeply aware.

Wisdom: a product of pain; perhaps of a nature we don’t recognize.

warmer/colder matters not for I thought/believed that the salmon would still be here after my time was up; now I fear I will see their demise and the planet just won’t be the same, for the salmons have survived many of the warmer/colder(s) but it appears they may not survive (us)

Mary, I hear you, but I think the deeply aware have more than two tools. At least I hope they do. Renewal is a thing that happens with or without us and our magic-killing properties. Renewal to what, I’m not so sure.

I grasp Rial’s scientific wisdom as the knowledge of the elders. He knows this planet is too complex for us to understand with our silly computer models. GIGO rules those who stomp around in emotional fits. I hope his ghost talks to us more often and for many eons to come.

Your writing is so beautiful Craig. You must be an expert!

Please always include me in your fascinating discourse