Sometime in the 1920s, somewhere in France.

A young girl from an influential middle-class French family had been found in a field, stabbed to death. There was no obvious perpetrator. The police rounded up the usual suspects – which is to say, immigrants – and found a Jewish door-to-door salesman who had been in the area at the time of the crime. Trouble was, there was no actual evidence linking him to her murder.

But the police wanted him for the crime anyway, so they hit on a bold new approach. They took advantage of a hot new technology called “cinema”. Specifically, they decided to try the world’s first filmed reconstruction of a crime. They found an actress to play the victim and somehow convinced their suspect to play the part of the murderer, complete with a knife, pretending to stab her with it in front of the camera; then they showed the flickering silent film to a jury. The hapless man was convicted. “Because the jury had seen it happen,” says Burkhardt Schafer, professor of computational legal theory at the University of Edinburgh. “It was just the power of the visual.”

At least, this how Schafer remembers the story from his legal studies decades ago. He’s been unsuccessfully searching for corroboration ever since. And for the past few months, so have I. I sent pestering requests to experts in film studies and history of cinema from UCLA to London.

No one can seem to alleviate the irritation with a nice cold draught of provenance. This frustrates both me and Dr. Schafer. “I even seem to remember the cover of the book where I checked the lecture notes I had taken,” he says. He still tells tells the story, though, because it illustrates how people get confused by new technologies.

Obviously, no jury would react this way to such a film today. Sure, they might be unwittingly prejudiced by it, but they would also understand that what’s depicted in a film didn’t necessarily happen. They would understand it as a reconstruction.

So you might be tempted to think of the people who believed this movie as gullible idiots. But before society got a handle on how to cognitively partition the idea of “cinema” (filing “here is a thing I saw” as separate from “here is a thing that definitely happened”), people didn’t share the intuitions we now take for granted about the medium’s limitations and inherent exploitability.

Those jurors were hardly alone in falling for the power of new media. Arthur Conan Doyle was fooled by photos that purported to show fairies among us. They were not fairies – they were double exposed photographs two girls had taken with paper dolls. Today we are shocked that anyone, much less someone smart and accomplished, could believe such an obvious fabrication. But it’s all about your priors. At the time, people didn’t have years of forged photos to make them skeptical. In fact, any suggestion of skepticism caused Conan Doyle to double down – instead of critically re-examining his beliefs, he spun up an entire theory about how fairies were made of ectoplasm and only became visible when a medium made contact. The creator of Sherlock Holmes staked – and to some extent, lost – his reputation on this hoax.

This sort of credulity often peaks when novel technologies are introduced, Schafer says. “The most dangerous period is often right after such a new technology is invented,” he says. That’s what’s happening right now with deepfakes, the AI-generated content many people believe are on the cusp of destroying the line between evidence and fabrication. The problem is not with the technology. It’s with what we want to believe.

Note: If anyone has any leads on the provenance of that French reconstruction story, please get in touch.

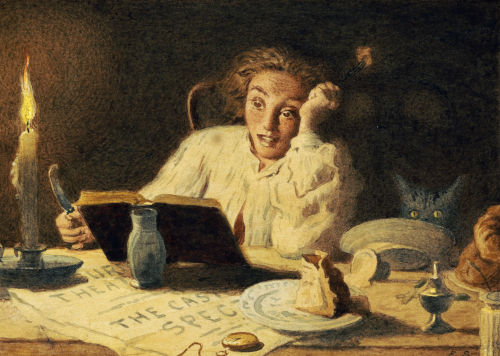

Image credit: The ghost story, watercolour, by English artist Frederick Smallfield. This work is in the public domain in England and other countries and areas where the copyright term is the author’s life plus 70 years or fewer.