Before I left for England, a surprising number of people pulled me aside for a frank talk about The Accent. You know the one. It’s that slightly off, trans-Atlantic dialect acquired by expats; the one whose distracting inauthenticity annoys you during otherwise decent period dramas. Fortunately for me, I was never in any real danger: I didn’t even speak English until I was eight, when I traded my native German for a Long Island-flavored New York accent, atop which I later shellacked a coat of Baltimore. The resulting mashup can withstand anything the Brits can throw at it.

Before I left for England, a surprising number of people pulled me aside for a frank talk about The Accent. You know the one. It’s that slightly off, trans-Atlantic dialect acquired by expats; the one whose distracting inauthenticity annoys you during otherwise decent period dramas. Fortunately for me, I was never in any real danger: I didn’t even speak English until I was eight, when I traded my native German for a Long Island-flavored New York accent, atop which I later shellacked a coat of Baltimore. The resulting mashup can withstand anything the Brits can throw at it.

But no one warned me about the phrases. Oh, their tempting little expressions! Chuffed! (Excited.) Gutted! (Very sad.) Naff! (Gross. [sigh, wrong. See correction]) And then there’s my personal downfall: “can’t be arsed.” God, I love that phrase. “Can’t be bothered” purports to mean the same thing, but it’s nowhere near as evocative. But when I attempted to slip it unnoticed into conversation last time I was back in the States, I got a very stern talking-to by our own Cassandra Willyard. “Sally, no,” she told me in plainspoken Midwestern. “No.”

I never said it again, but I couldn’t let it go. Why couldn’t I say “can’t be arsed”? When a Brit delivers the phrase, those three little words are transformed into gleaming pearls of wit. But in my mouth, that “r” is like hitting a ten-foot pothole in a clown car. I tried Americanising it by converting “arsed” to “assed,” but then you wonder what I can’t be “asked” to do, and what geographical circumstance led me to leave out the “k.” There’s no solution. I simply can’t say “can’t be arsed.”

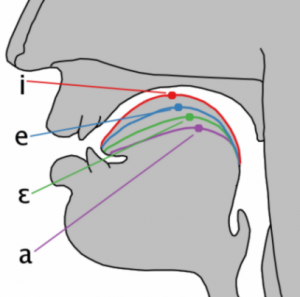

Having mastered three accents before age 20, I refused to believe that my trouble was as simple as a regional accent. Then I remembered hearing about phonemes. These are the smallest linguistic units that constitute a language: the “kuh” in can’t, the “buh” in be, the “ahhrrr” in arsed, the “sh” in Shh!

English has about 40 phonemes, but other languages vary widely. Rotokas, which is spoken in Papua New Guinea, has only 11 phonemes. At the other end of the spectrum is Khmer, spoken in Cambodia, which has hundreds. There’s a difference between learning a language and speaking it properly though. Speaking it accent free depends on the ability to properly move your lips, tongue and jaw to articulate them. The phonemes you physically can and can’t say supposedly “set” after the age of 11. I slipped in right under the deadline to avoid a German accent, allowing me to articulate the “th” phoneme that so notoriously trips up ze Germans.

So was the culprit that weird “ahhr” in “arsed”? Was that a phoneme or a dialect? I consulted Gennaro Chierchia, a linguist at Harvard. Nope, it wasn’t phonemes: “Phonetic differences are not used to distinguish words in English,” he said. Back to square one.

What was causing the difference? I dug deeper. That “aahr” wasn’t just in “arsed.” Observe what happens to the common phrase “blah blah” when you apply a coat of British.

Like all apparently off-the-cuff Britishisms, execution of this phrase is incredibly complex. I’ve managed to work out the recipe, but you must follow the directions to a tee or—not unlike “can’t be arsed”—this thing will blow up in your face like a meth lab.

1) Infuse everything with 8 gallons of your most Brrrritish accent.

2) Say the two words according to the following quantites: 3 parts aloof, 1 part bemused, 1 part impassive. Your tone should indicate that you’re so bored that your life is in danger.

3) Don’t forget a soupcon of self-deprecating amusement. You must end the second “blah” with a faint whisper of a smile that looks almost like it could transition into a snort, a way of acknowledging the in-joke between you and the listener. Was there an in-joke? There was now.

4) Add a head-shake so subtle that might be a vestigial shrug. Be careful to mete this out in homeopathic quantities.

If you like, you can leave off the second blah. A true Jedi master of Britishness can leave off the first one as well.

Call them phonemes or accents, those differences are what make British people sound smarter than us, no matter what they’re actually saying. Don’t believe me? Listen to this reading of Jersey Shore by persons with British accents. With an infusion of English, Jersey Shore dialogue is suddenly full of charming double entendre, though I assure you not one of those cast members is capable of even a single entendre.

I was truly gutted: To say the delicious phrases without sounding like a jerk, I would have to adopt the obnoxious accent. Which would make me sound like a jerk.

But there might be another way. Earlier this year, Washington University neuroscientist Eric Leuthardt figured out how to listen in on phonemes before a person actually articulates them, while they’re still rattling around in the preparatory language areas of the brain. (By the way, put away your tinfoil hat, because to do that, volunteers’ skulls had to be opened to allow a blanket of electrodes to be placed onto their exposed brains. Not exactly covert surveillance.)

Leuthardt is pursuing this research to help people trapped inside their own minds after a stroke or other traumatic brain injury. If you could pick up the brain’s phoneme signals, you could string those phonemes together into speech, giving someone with locked-in syndrome the chance to communicate normally (instead of the tortured eyeblinks Jean-Dominique Bauby was limited to while he wrote The Diving Bell and the Butterfly).

But for my purposes, I will highlight the much more frivolous implications: the benefits to Americans.

At some point, I hope Leuthardt’s phoneme-sipping technology will advance enough to give us all telepathic benefits without the invasive, skull-cracking drawbacks. At that point, I foresee an Android app that finally lets me convert English to American so I can impartially assess the quality of what is being said. We’ll see how blinded I am by the English wit and gravitas when I hear one telling me he can’t be “assed.”

image credit: Wikimedia Commons/ Ishwar

Turns out “naff” actually means uncool (thanks, Clare!). I was thinking of a different word that means gross: mingen. Return to post

You have nailed us to perfection. Kinell!

Very funny! But one teensy correction. Naff does not mean gross, it’s more like uncool.

Kinell! I love it. It’s practically steganography!

And Clare, it’s very British of you to provide the proper meaning. 😉

Kinell? steganography?

Kinell! It sounds like a sweet, quaintly Scottish expression, right?

Wrong! http://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=kinell

OK it’s not quite steganography–which is the art of sending hidden messages inside innocent-looking carriers– but it’s close enough. In my book, hiding your foul mouth inside an innocent-sounding phrase qualifies.

Sally, your transatlantic wit is making me laugh out loud! “Not capable of even a single entendre” is an insult worthy of Oscar Wilde.

I’m playing with “can’t be arsed” (fortunately I’m working from home) and I think it’s working for me. Now, I snuck an English accent into my collection of pre-age-11 accents (also South African and Canadian, my current choice) so that might be it, but I’m throwing in a bit of a Maritime spin. I’m fairly sure anyone from Newfoundland could say “can’t be arsed” without sounding stupid. Something to think about…

I get it now! I get it! k’in’ell. I’m using it on every occasion.

Great story!

This happens with foreign languages too. When I lived in Switzerland, I found that certain Italian or Swiss German words and phrases captured ideas in a way that English just couldn’t.

For instance, I kept hearing the Swiss German phrase “hura geil.” As in, “Dasch iisst hura geil,” and it obviously meant that “this is the most incredible thing that’s ever happened in the history of the world!” The guttural vowels of the first word followed by the staccato thump of the final syllable gave the phrase a rhythm that I loved and I started to use it. Then one day I asked someone what it actually meant.

Suddenly I understood what made the phrase so powerful and why I would never, EVER use it again. Its literal translation was: “horny prostitute.” When I told the waiter at the restaurant that the raclette he’d served me was “hura geil” I was actually saying, “it’s as awesome a horny prostitute!” That was the beginning of the end for me with Swiss German.

But Amy, can you do it without sneaking an “eh” at the end?

Also, never ask a British person where to find khaki pants, because “pants” are “underwear” and the way we pronounce “khaki” means “soiled.” Brits say khaaaaaaaaaawwwwwww-ki, but not frequently. I think it reminds them of their colonial past. And don’t talk about your stockings unless you’re wearing sexy thigh highs, and don’t compliment a male colleague on his suspenders because he will blush and stutter and eventually inform you that suspenders are the things that hold up the sexy thigh highs. In the UK the things men wear to hold up their trousers are called braces.

No word yet on what the things are called that fix your teeth. Insert obligatory dental joke here.

And actually, Amy, find a Scottish person to tell you they “can’t be arsed.” You will fall into a dead swoon. Cripes that accent is second to none.

Oh and Christie: Schwitzerdeutsch is a whole different animal from anything. I remember once spending a mind-altering evening in front of the TV in Zurich trying to comprehend the news. That was before I knew there was a Swiss version of German, which sounds almost like I should be able to understand it, but I’d maybe had a stroke.

Geil is a notable German expression though–though it originally meant “horny,” even by the time I was little it was just another way of saying “cool.” Adding on the modifier about the prostitute though? A new twist.

I started so I’ll finish. (Cue new post on peculiarly British catchphrases.) The teeth-fixing things are called braces here too. This may have led to confusion in the past, but not that I’ve heard. I’m just bridging the gap here with floss really, not at all getting to the root of things … oh, shut yer gob, Tim!

Very entertaining and, yes, that jibe about the Jersey Shore is worthy of Wilde.

You’d have fun with some of the New Zealand phrases. “Up the boohai” comes to mind.

http://www.chemistry.co.nz/kiwi.htm

Good stuff!

The ingrained phoneme thing does for British actors playing Americans. There’s a sound that always makes me wince because few get it right. I think it’s when they add ‘r’ sounds unnecessarily, as if all American vowels are ‘r-coloured’, or ‘rhotic’ as The Wikipedia Brain describes the effect.

The ‘RP’ English accent can cover all manner of sins, and Armstrong and Miller famously sent up youth speak via the pukka vowels of two wartime RAF officers. You may well have seen them.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m4QDz3c3Auw

Or…in Scotmode…you could say “dinnae fech yersel” which actually sounds quite rude in an english accent but isn’t. It just means “Don’t bother”. But it is very satisying to say out loud as is “Kinell”.

Don’t forget the glottal stop. Gutted with a plum in your mouth isn’t as effective as gu’ed, (or however a glottal stop is written).

naff is also used as a possible substitute for the “f” word, as in “Naff off…”.

I’m Australian, not British, but of course we share some vocabulary (not ‘naff’, though – the British have that one to themselves).

I wouldn’t say ‘chuffed’ meant ‘excited’, but I don’t know if there’s a word that will do as a substitute (some dictionaries suggest ‘pleased’, and ‘thrilled’ is also in the right ballpark). It’s like ‘proud’ only humbler, having connotations of surprise as opposed to entitlement. It’s the way you feel when a compliment really makes your day, or when your blog wins an award, or when something you do succeeds beyond your expectations.

Adrian, I have a burning question: I’d always thought “wingeing” or however you’d spell it, was an Australian word, but I saw it somewhere British lately. The Australian who told me about it used it thusly: “wingeing Poms.” Anyway, Australian? Brit? both?

@Ann – It’s both, and the online authorities say it’s originally British.

It also has its admirers in America, for example editor John McIntyre has written about it in several blog posts including:

http://weblogs.baltimoresun.com/news/mcintyre/blog/2010/05/topping_up.html

http://weblogs.baltimoresun.com/news/mcintyre/blog/2010/12/monoglot_america_just_gets_monoglotter.html

http://weblogs.baltimoresun.com/news/mcintyre/blog/2011/04/rounding_out_the_day.html

(I second his recommendation for Lynne Murphy’s blog, btw.)

Adrian, those are excellent links and thank you. Lynne Murphy scared me a little but i think Sally would love her. What I can’t get over is an Australian sending me links to my hometown newspaper. Small world. Globalization. Something that didn’t exist when I was a tad (American: small person, child; also Brit? Australian?).

Take heart, they can’t say some of our words either. It almost hurts to hear an Englishman say ‘dude’.

Ever hear a Brit try to say “fughetabouddit!” (forget about it)? Or really for that matter any of the dialog from Goodfellas? Brilliant.

Casey, Amanda, my next project is to make the British people in my life say “dude” and “fuhggedaboudit.” It’s only fair, because they make me say “wanker” and then point and laugh. (No they don’t. They do something like a homeopathic smirk.)

And Adrian– brilliant! Lynne Murphy, am so happy to have been made aware of her. Thanks!

And dinah and Michael– It’s a strange world in which the phrase “up the boohai” is completely anodyne. Same goes for “gutted with a plum in your mouth,” which to me sounds unspeakably dirty.

Thanks everyone! I have a new reading list and a compendium of more delicious phrases I don’t stand a chance of saying! Thanks for the tips.

Cheers, as my people say-

Wow. What a great read. Now I understand Captain Picard’s simple “Engage” and “Make it so” Have to be a Shakespearean actor to say it just so.