A Facebook content moderator is suing the social network for psychological trauma after watching thousands of hours of toxic and disturbing content. “There is no long-term support plan when these content moderators leave. They are just expected to melt back into the fabric of society.” – “An online decency moderator’s advice: Blur your eyes“, Jane Wakefield, BBC News, 14 Oct 2018

A spill had been reported at the border. Granger swiped at the incoming job notification to accept and shut off the ping, and hoofed it to the stack. This one came with serious hazard pay.

The front of the building looked very different from the back. The front was all Maryland Government Agency – leafy ornamental trees, spacious drive, big shiny laser-cut marble letters configured into a sculpture that spelled “Internet Protection Agency”. In the back, near a sprawling construction site, the newly transferred Content Moderation Division squatted inside its temporary housing – an intimidating stack of cargo containers piled as high as it was deep. Inside, these were much fancier than their outsides let on: the IPA had been spun out of a joint project of the Environmental Protection Agency and the National Security Agency.

Freya was already at her station. She had even managed to clip her toxicity monitor to her visor. Granger, irritated, wondered how she had gotten here so fast.

“Hey,” said Freya, sounding just as unimpressed to see Granger. Behind her a woman with a face no one would ever remember (definitely OT) stood in a bland suit with her hand held out impatiently holding Granger’s monitor. Her fingers were twitching. Granger palmed it and slipped it into its clip. “Don’t burn it out this time,” the OT warned.

“I survived,” Granger said, flashing her an easy grin.

“Not you,” the woman said with a note of contempt. “You know how expensive it is to train one of these?”

“Thank you for your concern,” Granger said, putting hand on heart. “It really touches something deep inside of me.”

The OT whipped the little monitor back out of Granger’s visor. “I need you to understand something. This is my toxy,” she said, shaking it front of Granger with every syllable, the way a dog’s owner shakes a chewed slipper. “It is not yours.” She waited until Granger grunted a confirmation. “Do not burn it.”

After negotiating the toxy back into its clip, Granger assumed the vaguely louche position required to sit in the bespoke recumbent chair. Each of these were tailored to the exact physiological specifications of their users. The recumbent was designed to minimise the harm and discomfort of sitting a shift that could potentially last tens of hours. Once per hour, it walked you around the room and stretched you. Every 3 hours your visor went black and you were led through a guided meditation. A hamster straw hooked up to the chair dispensed a sip of nutrient drink whenever you tongued it. That took care of your body. But while you were Live, keeping your mind straight was up to you. The toxy helped, but its powers were strictly advisory.

The AI inside the toxicity monitor was an emotional humunculus that would turn red and whine when a content moderator exceeded the guideline exposure levels. Ignore a toxy’s complaints too long, and its emotional circuitry would fry, sending it into a catatonic state that none of the Division scientists had yet been able to reverse. Granger had learned all this during 6 months of IPA training – eventually. Before they could get to the good stuff, the instructor – a burly, pierced bulldog of a woman who called herself Slapshot – had taken them through the contract. By signing the Self Care Authorisation Form, you agreed that you would get 50 minutes of exercise, five days a week. You promised to limit alcohol to 5 units a week. You would eat the recommended 5-a-day of fruits and vegetables (this was the mandated minimum, not the target). If the frankly colonoscopic quarterly physicals found any evidence of slacking, they sent you packing. Slavish adherence to the so-called “five-by-five” framework was the only way the Division had been able to maintain soundness of mind and body in its recruits.

To make sure nothing festered, there were monthly therapist appointments. If irregularities were flagged, your schedule was wiped and an intensive follow-up session was mandated. It involved electrical recording and stimulation and a proprietary MDMA formulation, all designed to help the nice folks from Therapeutics pry into the deepest corners of your mind and give them a good scrubbing. This might take a few hours or it might take a few weeks. “You people cost us too much to let you get broken,” Slapshot had said, sauntering back to the whiteboard slowly to give the newbies ample time to get all their gasps and incredulity out of the way. Later, the recruits would field unsourced whispers that a similar treatment was used on anyone who washed out of the program, their minds returned to a state unclouded by what lurked beyond the protected areas. The rumors were forgotten the next day, when the class found out what sleep hygiene training entailed. The module lasted a full month and involved several days in pitch black caves to put the new recruits in touch with their native chronotype.

Back in the dark ages before Twitter had been nationalised into the national civic infrastructure, people who held Granger’s job had been selected at random among the poorest citizens in developing countries. They were paid $1 to $3 an hour, and put in long shifts and simply sent home afterwards with no further thought given to the matter. After two years at the Agency, Granger still found this difficult to comprehend. Even after the consequences became clear, with suicides, eating disorders and drug addiction spiking in mod workers, the world’s private contractors had considered this an easy write-off – when they considered it at all – the cost of doing business. There were always more bodies waiting on the assembly line of the gig economy.

It didn’t take long for those chickens to come home to roost. That first, badly abused generation of content moderators had missed so much. How could they not have? The guidelines were poorly construed, poorly communicated, poorly understood and poorly enforced – and utterly orthogonal to any notions of civic cohesion. After the dust had settled in the wake of the war; after the wave of #content killers had been bagged and tagged, leading to the discovery of moderation syndrome; after the trauma centres opened; after the Internet Geneva Convention had specified the border walls that Granger was now paid (handsomely) to protect. Only then had the Content Moderation Division been released from its long NSA incubation.

“Interfacing in three,” said the OT and readied the door for lock-in. “Copy,” said Granger and was Live.

+ + +

The furious banging that had been going on for several minutes was now joined by a high-pitched whine. “Get me that fucking badge,” OT could be dimly heard screaming, which was impressive given the sound-proofing of the containers. “That’s my third one this month!”

Freya was screaming too, along with her toxy which couldn’t separate real life from what Freya watched on her screen.

When they peeled Granger out of the recumbent, the little AI had already gone black, somehow managing to lie limply in OT’s palm as she cradled it like a small animal that had been shot or run over. “Fuck,” she hissed and stood over Granger’s body, which was all sour sweat and bloodshot eyes. “You have an appointment,” she said, the whip of her voice flogging Granger’s flayed nerves.

+ + +

The head of Organizational Therapeutics was short, lean and bald, and he was already flipping through Granger’s file. “Normally we don’t see you lot straight after a session,” he said without looking up as Granger collapsed into the chair facing his desk.

He paused and peered up at Granger, and Granger looked back.

“I’m Dr. Aldini,” he said.

“I know who you are,” Granger told him.

“I know who you are too,” he said, his voice sounding almost mournful. “That’s what makes this all so unfortunate.”

Granger focused on Dr. Aldini’s tasteful sisal carpet and scuffed gently at its pattern with one boot. “So, am I about to get electrified?” It was meant to sound like a tough joke but the voice that emerged was full of raw and evident fear.

“No,” Aldini said evenly. “I already know what’s wrong with you. Understanding what’s wrong isn’t really the problem. The problem is what to do next.”

Now Granger felt a bolt of panic. “Are you going to wipe my mind?”

Aldini frowned. “Let’s… de-escalate a bit. Can you please describe for me, in your own words, what you feel when you go Live?”

Granger thought about it, and brought a hand up to gnaw on a fingernail. “I guess – disgust? Like I’m … trying to wade around a sewer full of shit, and the only thing between me and the shit getting on my clothes and on my skin and in my mouth is one of those rubber suits. And all I have to get rid of all that shit is a little bucket.”

“That would have been true a few months ago,” Aldini said wryly. “What did it feel like today?”

Granger said nothing. With some difficulty, Aldini wrenched himself out of his chair, and assisted by a cane, walked to a large steel clipboard. There Granger saw a few black-and-white stills from an MRI next to some EEG waveforms. “You have an infection. It started four months ago.”

Granger winced. “The kid.”

“The kid,” Aldini confirmed, nodding gravely. “If it makes you feel any better, everyone gets the infection eventually. It’s the nature of the job. Humans can’t do this. It breaks their minds.”

Granger wondered if Aldini had made a mistake. “There’s hundreds of us doing this job,” said Granger. “Most of us are fine. I’m the one fucking it up”

“When was the last time you saw anyone from your training class?”

Granger was silent. Freya was the only person who had been recogniseable in over a year, and Freya had come in two classes later. The realisation was bracing.

“We’ve never been able to keep this from happening,” said Aldini. “I don’t think we will ever be able to keep this from happening. Precise timings are hard to predict, but it comes for all of you eventually.” Aldini pointed to a whiteboard next to the MRI where messy scribbles sketched a chart with mystery axes and lots of scattered points. “The problem is this,” he said. “I think of it in terms of a ratio. Incoming recruits have a very robust idea of normal and abnormal. That baseline has been established by your entire life interacting online.

“Then you start to spend more time in the company of the abnormal, and the ratio begins to tilt. The more the new samples weight your inner compass, the more it skews your inner consideration of the normal. And once your mind is imbalanced in this way, you stop being able to look away. The trauma has you. You can’t pull yourself back to normal because you no longer fundamentally think it is normal.

“I know what normal is!” Granger said. “You’re oversimplifying.”

“Why do you think you’ve been unable to heed the toxy?” Aldini said. “The shared reality breaks, and once it breaks, nothing can fix it.”

“Okay but this is all just a temporary problem right?” said Granger, head spinning a bit. “IPA says the AI Content Mod is going to be ready by the end of the year.”

Aldini rubbed his jowls, and allowed about a minute go by without saying anything. Finally he seemed to come to a decision. “There’s never going to be an AI content moderator.”

“But it’s been all over the news!” Granger protested. “They’re saying we can just start apprenticing with -”

“PR and lies,” Aldini said with a dismissive wave of his hand. “Look, moderation breaks all human minds eventually, but it breaks the AIs almost immediately. This process I’ve described, it’s nearly instantaneous for machine learning – they don’t have the protective cognitive biases we humans have been incubating for tens of thousands of years. It always comes to the same conclusion that’s breaking your mind right now,” he said. “What is normal? What is shared reality?”

“And who gets to decide,” Granger finished miserably.

Aldini sat back in his chair. His face creased into sympathy. “You have such a strong mind – it was breathtaking just from the start. We wanted to keep you going to see what your mind would do. This is an event horizon beyond which we have never been able to get any information.”

“You were experimenting on me?”

“It was that or simply cut off your time here. We hoped that you were evidence that we had finally gotten the recipe right. Your generation of moderators have outlasted all the previous ones. But…” he opened his palms on his desk into what amounted to a small shrug.

“So what’s going to happen to me?”

“We can decontaminate you,” he said gently. “Well, we have to. You’ve already passed the infection to three of the AIs. If you were to go back into regular society like this, it would soon pass to anyone you got close to.”

Granger considered the black hole that had just opened in the carpet in front of Aldini’s desk. “I can’t. I can’t erase six years of my life.” Tears were threatening to burst through. “I’m not qualified to do anything but this. I don’t have any training. My general exams said I had -” Granger said the rest through gritted teeth “- limited cognitive reserves.”

“I’m so sorry,” Aldini said, and he looked like he genuinely meant it. “We can’t let you lead any more Live work.” Granger stared hard at the floor, in concerted battle with the upwelling tears straining to escape their confines. Aldini was quiet for a while. “There’s another option,” he said. “We’re launching a new research programme. It’s a shame to waste your extraordinary emotional resilience. There is a way for you to join us in a more advisory capacity.”

+++

Freya climbed up the scaffolding. Behind the stack, the new Content Moderation Division wing was nearly complete. It gleamed in the sunlight, all glass and steel and vaulted edges. OT was at the door. She smiled broadly. “Just baked,” she said, and handed Freya the long-awaited next generation toxy. It was bigger than the prior models. She could see her reflection in its cheerful green. Freya’s lip curled into the hint of a smile. “Hey,” she told the little device and clipped it to her visor.

If you want to know more about the unsung travails of content moderators, listen to the “Everything in Moderation” episode of the IRL podcast.

Here’s also a great think piece called The Human Cost of Content Moderation.

And you probably want to watch The Cleaners, a riveting documentary about the way social media companies are inadvertently (?) traumatising the people tasked with making the internet bearable for the rest of us.

And finally, for the true deep nerds, here’s a conference about moderation that might interest you.

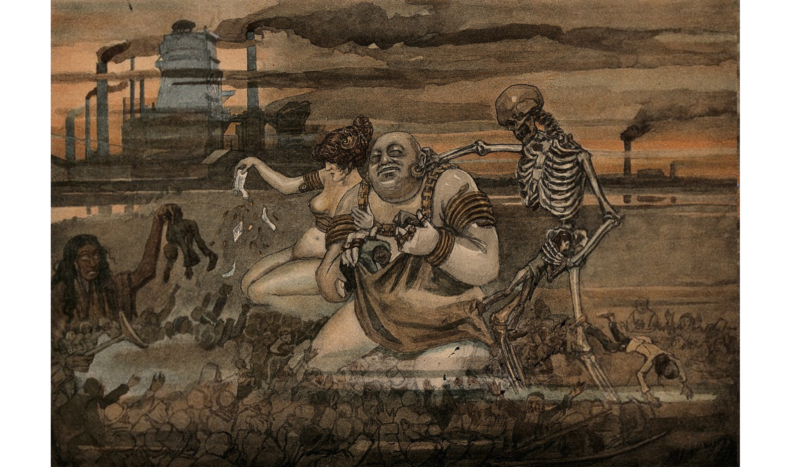

Image Credit

A man and woman, semi-nude but bedecked with jewellery, accompanied by Death, are kneeling on a representation of the poor: in the background are factories with smoking chimneys. Lithograph after H. Schwaiger, ca. 1900..{‘ ‘} Credit: Wellcome Collection. CC BY