Sometimes I lose track of time when I’m in the water. There are days when it seems like I’ve been paddling through whitewater for hours, the wind makes my ears feel like icicles, and my arms are burning. When I get back to the car, only fifteen minutes have passed since I started surfing. Then there are days when the sky is blue, the waves are just right and there’s a friend to chat with between sets. On those days it seems like I’ve hardly been in the water at all. And on those days I have sometimes been late to pick up my kids.

Sometimes I lose track of time when I’m in the water. There are days when it seems like I’ve been paddling through whitewater for hours, the wind makes my ears feel like icicles, and my arms are burning. When I get back to the car, only fifteen minutes have passed since I started surfing. Then there are days when the sky is blue, the waves are just right and there’s a friend to chat with between sets. On those days it seems like I’ve hardly been in the water at all. And on those days I have sometimes been late to pick up my kids.

A few weeks ago, I remembered I had an old-school solution: a watch. I’d gotten one a few years ago to address this same issue, but I’d hurt my back last spring. Unused, the watch had migrated to the back of a drawer. Last week, I dug it out and my husband kindly put in a new battery. The little black numbers reappeared. I fiddled with the buttons until the watch caught up with the time it was now.

I’d picked this watch out because it was water resistant and had a built-in tide chart, which I thought would be handy for figuring out when to surf. My favorite part was a shark fin that swam across the face when the minute changed, something that one of my son’s friends loved, too. (It was nice to be able to quiet a group of preschoolers by having them sit in a circle and watch for the shark.)

This time, when I strapped it on, I found myself wondering about how far it could go. If all goes well when I’m surfing, I don’t usually spend much time submerged. But my watch boasted that it could go up to 100 meters underwater. If I ended up that deep, I wouldn’t be needing to know what time it was anymore.

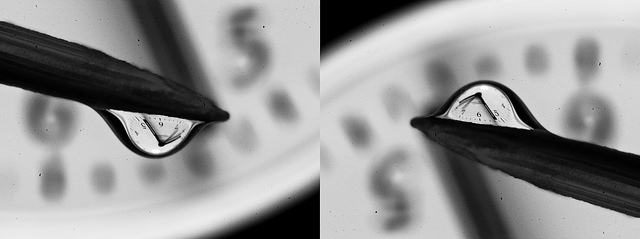

But that’s how watches explain their water-worthiness. In the 1960s, the Federal Trade Commission banned the use of “waterproof” to describe watches. Water can always find a way in if conditions are right. Watchmakers now use the term water-resistant, and provide the amount of pressure a watch can take before water takes over. Those that are water resistant to less than 100 meters aren’t suited for much more water than handwashing or an unexpected rainstorm. Dive-specific watches have a series of tests they must undergo to meet an international standard, including a 50-hour submersion test and two hours of pressure at 125 percent of the pressure the watch will be rated.

But that’s how watches explain their water-worthiness. In the 1960s, the Federal Trade Commission banned the use of “waterproof” to describe watches. Water can always find a way in if conditions are right. Watchmakers now use the term water-resistant, and provide the amount of pressure a watch can take before water takes over. Those that are water resistant to less than 100 meters aren’t suited for much more water than handwashing or an unexpected rainstorm. Dive-specific watches have a series of tests they must undergo to meet an international standard, including a 50-hour submersion test and two hours of pressure at 125 percent of the pressure the watch will be rated.

Even without so much pressure, all sorts of things can happen to a watch. Seals get old, seawater corrodes the case. A watch can get dropped or baked in the trunk of your car. Even diving into the water with a water-resistant watch can create enough force to damage it over time.

Last Friday, I paddled out with my re-energized watch. I felt re-energized, too; the back injury had been a perfect storm of different weaknesses, and after more than a year, I’d strengthened everything to the point where I wasn’t afraid to get in the water anymore. I found the perfect place to sit in the lineup. I caught wave after wave, and everything felt easy. I had to make it back to town by noon, but it couldn’t be noon quite yet. Finally, I looked at my watch.

A woman was sitting on her board a few yards away. I paddled over to her. “Do you know what time it is?” I asked her, and I showed her my watch. The face was blank again: no numbers, no tide, and no relentlessly punctual shark. What combination of pressure, water and time had finally caught up to the inner workings?

The woman looked at my blank watch, and apologized for not knowing what time it was. “That’s okay,” I said. “Maybe it means time doesn’t exist when we’re out here.”

She laughed. “That’s true,” she said. “Unless there’s somewhere else you have to be.” I caught two more waves and paddled in. The watchband broke apart and fell off my wrist as I walked back along the beach. When I got back to the car, I found I still had plenty of time.

*

Images by Shena Tschofen and tata_aka_T via Flickr/Creative Commons license