This fall, I brought members of the Oregon Peace Institute to my town to lead an introductory bystander intervention training. The fatal stabbing of two men on a Portland commuter train a few months earlier had hit the community hard—many people had connections to the places and people involved—and I wanted to do something more than mourn. I chose to organize the training because friends (including Person of LWON Helen Fields) told me that it was a good crash course in how to better help others, both in extreme situations like that surrounding the train stabbing and more everyday instances of harassment.

This fall, I brought members of the Oregon Peace Institute to my town to lead an introductory bystander intervention training. The fatal stabbing of two men on a Portland commuter train a few months earlier had hit the community hard—many people had connections to the places and people involved—and I wanted to do something more than mourn. I chose to organize the training because friends (including Person of LWON Helen Fields) told me that it was a good crash course in how to better help others, both in extreme situations like that surrounding the train stabbing and more everyday instances of harassment.

They were right: The bystander intervention model is both a very practical set of tactics and a small but profound shift in attitude, and its approach is tremendously helpful to the everyday business of being a decent person, no matter who you are or what your situation might be. For scientists and science students (and science writers, for that matter), bystander intervention can be a powerful weapon against the chronic problem of sexual harassment in the lab and in the field. With that in mind, here are the basics, and some resources for learning more.

What is a bystander? Many anti-bullying organizations define a bystander as someone who sees or knows about an instance of bullying or other form of harassment. Bystanders can either be part of the problem (hurtful bystanders) or part of the solution (helpful bystanders). So if your lab manager tells a joke that insults a fellow student, you’re a bystander; if a coworker tells you the PI is harassing her but you haven’t seen it happen firsthand, you’re a bystander. As a bystander, you can choose to be hurtful or helpful.

Why don’t bystanders intervene? Lots of reasons, some obvious and others not. They may simply not notice what’s happening; they may think it’s none of their business; they may be afraid of getting hurt themselves; they may be afraid of making things worse; they may be afraid of being criticized or ridiculed; or they may simply not know what to do. In science, where the power differential between graduate students and their supervisors is often extreme, students may fear that helping another student will put their own funding—and their own career—at risk.

Start learning to intervene. The first step is simply to listen and watch for the many different kinds of harassment. (If you don’t usually stand out in a crowd, try putting yourself in a situation where you do stand out, and notice the ways in which you feel vulnerable.) Then, when you see someone who’s being targeted, or who you think is being targeted, check in with her or him: Was that a weird joke? Does he or she need help, or even just company, in this situation? As our Oregon Peace Institute trainers gently but firmly reminded us this fall, bystander intervention isn’t about you. Your safety is important—more about that in a minute—but your focus should be on the person being targeted and what she or he says she needs, not which actions are going to save you embarrassment or make you look like a hero.

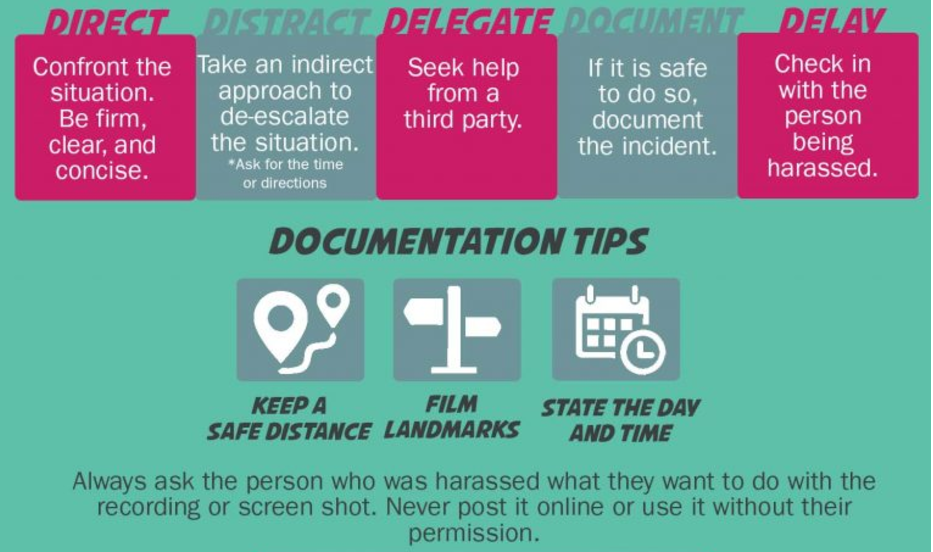

Remember that you have a choice of tactics. Bystander intervention might involve a direct confrontation with a perpetrator, but that’s just one of several ways to intervene, and your response should depend on the situation and the people involved. Often, the safest and most effective approach to an active situation is to distract the perpetrator, using indirect tactics like the one in this viral cartoon. (Effective distractions can be as simple as spilling coffee, standing in the way with a snack, or interrupting a conversation with an unrelated question.) You can also delegate intervention to those with more power to resolve it, especially in non-emergency situations: if the person being targeted is a graduate student and you are too, the best intervention might be to support your colleague as he or she approaches university authorities. Whenever possible, document the harassment with a video or audio recording, or notes taken immediately after the incident.

Practice. Our trainers had us practice intervening in a number of all-too-familiar scenarios, including on a bus when a fellow passenger is being harassed (one especially creative workshop participant started loudly threatening to throw up nearby, which distracted the perpetrator), and in a grocery store when a customer seems to be on the verge of hitting his or her child (another participant simply walked between the father and child, then distracted the father by asking how his day had been). You and your colleagues can practice responding to situations you’ve experienced or might experience in the lab and field, not only spreading knowledge but also building trust within your research team.

Bystander intervention isn’t the whole solution to harassment in science, of course, but it’s something anyone can do to make research safer for everyone. For more information about bystander intervention tactics and trainings, see Hollaback, the National Sexual Violence Resource Center, or this list of resources from CampusClarity.

Top photo from Flickr user Antarctic Bound. Graphic courtesy of Hollaback.

One thought on “Sticking up for Your Colleagues, in the Lab and in the Field”

Comments are closed.