Last Sunday I saw a mountain lion, a full body profile, spotted from a dirt road. Healthy size and age, tail like a rope. By the time we backed up the truck, it was gone, disappeared into a brambly ponderosa forest. I don’t know why, to find tracks, or a scent, I jumped out and hurried to the spot where the cat had been. From there, I could see it sauntering into the woods, tail swaying, not noticing I’d pranced up 50 feet behind it.

That would have been the moment to stop. The Monday morning quarterback in me says move to your haunches and watch. Stay still. You may never see a mountain lion walking with such candidness, shoulder blades rising and falling with every soft step. Too understand the life of an animal, it’s best to see it without it seeing you.

Instead of staying put, I signaled to the driver that I was following the cat.

I’ve done this before, not with the cat, but with greed. I’ve wanted more than I should, pushed the bubble that much farther. I didn’t have a gun, or really a plan. I wasn’t a hunter. But I didn’t want the mountain lion to be gone so quickly.

A few decades ago I was on top of a rock dome in Utah when a bighorn ram wandered beneath me. He had no idea I was above him on my belly watching muscles shift along his spine. I could have dropped a pebble on his back. When he began to exit, I couldn’t help myself, and clucked my tongue. This casual, unposed creature came to full, electified attention.

Was it my wanting the moment to last longer, the engagement to deepen? To be part of the conversation? Humans are so damn lonely, hardly room for anything but ourselves at the top, we’d do anything to catch the eye of another species, no matter what it might do to them.

The ram bolted, then turned to face me, where we had sort of a standoff that ended in the ram snorting and walking away, as if saying I weren’t worth the effort. When it walked off, it seemed annoyed. I felt exhilarated with a pounding heart, but I also felt invasive, untempered. I’d broken a spell. Until I clucked my tongue, the animal had been fluid, like it had a breeze drifting through its body. I’d heard the steps of its padded hooves on stone, as if I’d been let in through a secret door.

With the mountain lion, I should have stopped, but I felt like a cat myself, batting uncontrollably at a bob of yarn. I moved my weight lower in my body, half-crouched, stepping lightly around fallen branches, trying not to make a sound.

A cottontail flushed from a bush. The rabbit must have been terrified, first crossed by a mountain lion, then by me. It couldn’t handle the stress and it bolted. I froze. The cat didn’t look back. It was in the snow globe of its own head, moving through another day in the life of a large cat. It can’t look back at every scamper and squawk in the woods.

I’ve been alone in the company of mountain lions before. I have seen their movement, their musculature, looking them in the eye through woods or a desert canyon when all the brochures say not to. You can’t help it. You are two animals; you look at each other. I held a dead one one winter where it had frozen in the snow at the base of a spruce tree, the place it picked to die. There I took a close look at its ivory canines, the heft of its paw. In wildland settings like this, mountain lions specialize in eating native herbivores, deer and elk. Around Urban interfaces you see a greater use of exotic and invasive species, and incidentally far more human attacks. This according to Moss et al. In one world it does what it always did, and stays clear of humans. In another it is behaviorally evolving, becoming a different sort of animal. I lean toward the older, wilder kind. The dead lion was in the middle of nowhere, western Colorado, its life spent mostly without us.

Maybe it wasn’t greed that sent me after the mountain lion. I was counting coup. Seeing more than I should, getting in close to an animal rarely seen.

Let’s call it curiosity. I stepped on the tip of a dead branch. The lion flashed a quick glance at me and like water, was gone.

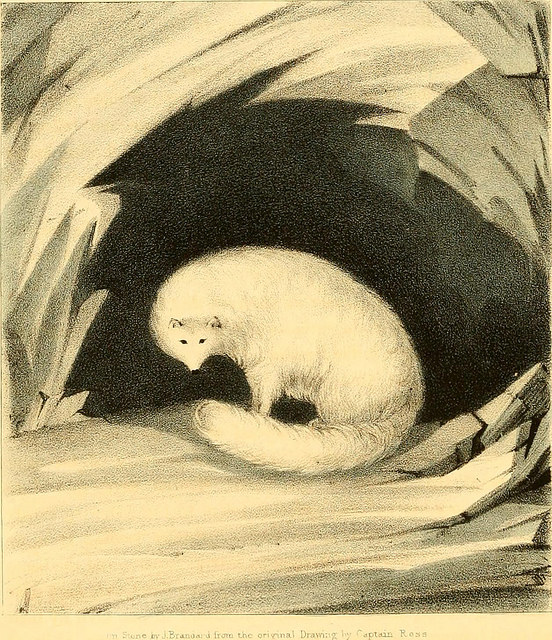

Image: “Narrative of a second voyage in search of a north-west passage, and of a residence in the Arctic regions during the years 1829, 1830, 1831, 1832, 1833” from Internet Archive Book Images.

Such a beautiful and heart stilling moment in time.

Your words always fill me with the experience.

Thank you!

We are on the hunt for our severed wild legacy

Curiousity. And the insatiably need to touch the wild.

Largest cat in the New World?

Brian, caught that, thanks, jaguar, forgot about those other new worlders.

Yes, counting coup. We begin life with innate acquisitiveness, and that doesn’t usually disappear in adult life. Thus we engage in hunting, birding, collecting, possessing, and other symptoms of our desire to possess. Sometimes the possession is an experience, perhaps not even with a photo to mark it. But possession all the same. Some of this innate acquisitiveness, which was likely so important to our ancestors, now can lead to extreme possessiveness in a commercial society. We may see it as cultural weakness, destructive to our world as our population spirals out of control, but there is an evolutionary tendency behind it, and we need to learn to temper that and be satisfied with less (which can be more). However, don’t you be content with spreading less prose! That is something I must collect.

Really catches the moment and feeling when we are lucky enough to witness such things.