My alma mater is, for better or worse, the undergraduate equivalent of a cult film: Most people have never heard of Reed College, and the few who have really like to argue about it.

So it’s disconcerting when arguments usually confined to the Reed campus attract national attention. In recent days, a Washington Post column and a much-read Atlantic article have described, in disturbing detail, ongoing student protests against the perceived Eurocentrism of Humanities 110, a rigorous, year-long examination of the ancient Greeks and their neighbors required of all first-year Reed students. Since the protests began, in September 2016, protesters have repeatedly disrupted classes, intimidated lecturers, and bullied other students both online and off. (To be clear, the mission of Reedies Against Racism, the campus group that started the protests, is broader than Hum 110 reform, and its stated demands are less extreme than some members’ rhetoric and behavior suggest; that context is little comfort, however, to the students and professors who have been insulted and harassed.)

Many Reed alumni—most of us no strangers to political protest—are appalled by these tactics, and plenty of current students are, too: this fall, a large segment of the incoming class, led primarily by students of color, has called for the restoration of order to the Hum 110 lecture hall.

Obscured by the campus cacophony, though, is a worthwhile—and necessary—discussion about whether anyone should read the ancient Greeks in the first place, and if so why and how. That discussion has been underway at Reed for decades, and with any luck it will continue for decades to come. As someone who took Hum 110 more than twenty years ago, the news from campus has made me reflect on what I learned in the course. The answers, both equally true, are that I didn’t learn very much. And that I learned everything.

I didn’t learn very much in Hum 110 because I was seventeen, half-asleep—lectures were and still are held first thing in the morning, three times a week—terribly shy, and recently heartbroken, with only the foggiest sense of how fortunate I was to attend a small, selective, and expensive liberal-arts school. (In other words, I wasn’t unusual among Reed students, then or now.) I slogged through the Hum 110 readings and wrote the required papers, but I can’t say that the words of Herodotus, Sappho, or Homer really sank in.

And yet they did. What I learned in Hum 110 is that so-called Western civilization is a narrative much like any other—except that it happens to affect just about everyone on earth. No matter where we were born or what we look like or what we believe, the narrative of Western civilization is part of the cultural water we swim in. By taking me back to the origins of that narrative, Hum 110 did me the great favor of hauling it into view—and impressing me with the universal right and duty to question it.

Members of Reedies Against Racism argue, in their calmer moments, that Hum 110 simply perpetuates the most familiar version of the Western civilization narrative—that positioning Plato and Aristotle at the very center of the college curriculum helps ensure their continued influence, along with the continued silencing of other voices from the past. This is worth considering: the study of classical literature is, historically and indisputably, extremely white and male, and those perspectives have unduly shaped the narrative that’s shaped all of us. As the field of classics has diversified, its members have started to recognize and reform its longstanding blind spots, but it’s a slow process. At the same time, members of far-right groups are enthusiastically adopting outdated views of the ancient world to further their own noxious ends. (Dudes: just because the statues are white doesn’t mean the people were.)

To many of the campus protesters, then, the Hum 110 syllabus looks like a monument overdue for toppling; online discussions have even compared it to the Confederate flag. But after taking the course myself, and digesting its lessons over half a lifetime, I don’t think this analogy holds up. The syllabus was revised many times before I walked into the Hum 110 lecture hall, and it’s been revised many times since. New critical perspectives have been added, the geography of the course has expanded, and original texts have come and gone. (Another revision, accelerated in response to the recent protests, is forthcoming this fall.) The readings are more diverse than they were when I was at Reed, as are the professors who teach them and the students who read them. This is not to say that the syllabus is perfect—far from it. It’s to say that it isn’t carved in stone—and unlike a monument or a flag, it’s not meant to teach reverence. In fact, Hum 110 is intended to teach precisely the opposite.

In my experience, the Hum 110 syllabus wasn’t a tool of exclusion but a route to inclusion. Hum 110 gave me the gumption to alter the modern-day holy text of Tolkien so that my daughter can see herself in it; it taught me to adore seeing Medea relocated to contemporary Los Angeles, or Julius Caesar performed in fatigues, or Hotspur and Lady Hotspur played by two women. These are small things, but they’re part of a general attitude I acquired during my first year at Reed. I respect the beauty and boldness and skill displayed in all these texts, and I respect the expertise of those who devote their lives to studying them. But I learned in Hum 110 that to respect a text is to keep experimenting with it, and keep testing its relevance. Some of these works have already survived thousands of years of scrutiny; let’s see if they can take a few millennia more.

Not long ago, a friend of mine told me about some classical theater she’d seen. “I enjoyed it,” she said, “but I don’t feel like it’s really mine.” She wasn’t talking about representation, about whether someone who looked or acted like her had appeared on stage. She just felt that despite her smarts, and her multiple graduate degrees, she wasn’t familiar enough with the work to engage with it. I barely remember enough from Hum 110 to fill in the classical clues in a crossword puzzle, and I’ve never studied literary criticism in any serious way. But by exposing the roots of the narrative known as Western civilization, Hum 110 opened a door to me that’s never closed.

While I’ve doubted myself in many ways during the two decades since I took Hum 110, I’ve never doubted my and others’ right to question anything and anyone, from the epic of Gilgamesh to the tall tales of our present-day kings. What I really learned in Hum 110 is that the ancient Greeks—and the rest of our collective cultural ancestries, for that matter—are mine. They’re mine and yours and theirs and ours, to honor with our sharpest spears.

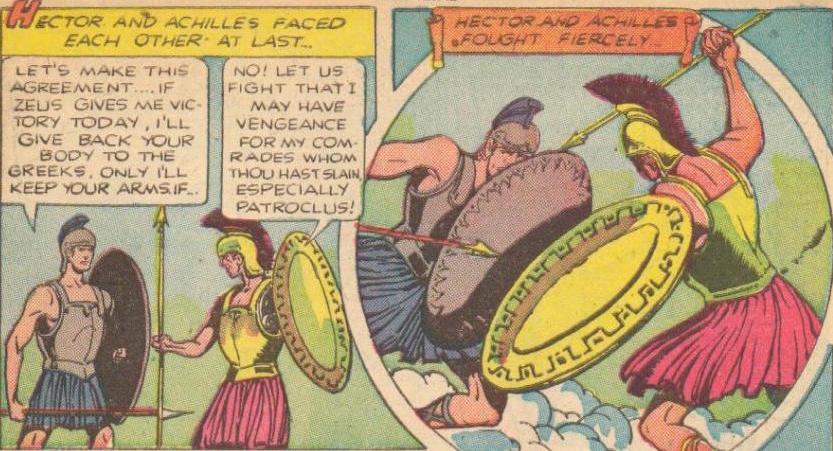

Top: Panels from the Illustrated Classics adaptation of the Iliad, published in 1950.

Thanks, Michelle!

Thanks, Michelle. This is terrific!

I love it: Reed as cult film! But which one??

Nice stuff! Feel free to still drop a piece for HCN once in a while.

I’m very curious about what is currently in the HUM 110 syllabus? Are there diverse voices or isn’t only dead white guys? There is absolutely value in reading Plato and Aristotle, but it’s value is greatly enhanced if it’s read alongside critiques from people of color. Cedric Robinson, H.L.T Quan, I could these and more be a great addition to the HUM curriculum if they are not already.

The demands linked above speak to restoring justice for students of color on campus. They are specifically talking about structual issues that exclude and silence people of color. It’s a shame that so much of the writing on this topic has not addressed those specific demands but has instead focused on the protestors tactics and an emphasis on what they should be doing. What about the schools policy for hiring black tenured faculty? The cost of their meal plan program? What is currently on the damn syllabus? Why is there not more writing that gets at these issues specific?

The link to current and past Hum 110 syllabi is in the post above, and here: http://www.reed.edu/humanities/hum110/index.html

Thank you! I don’t know how I missed that haha. Just browsing it, at a glance I agree with the students, it’s not nearly diverse enough. Black Athena would be another great addition to this syllabus. There is no reason why the class can’t read some of the foundational texts like Plato and Aristotle, Greece was not the only contributor to the development of the western world though and an honest and thoughtful course would reflect the struggles that women and POC have faced and their stories of their survivial. The course would be greatly enriched if it was built around this complexity. And hiring more tenured faculty of color would help it get there.

These are important issues, the demands of the students are totally reasonable, it would be great to see more folks writing about those demands.