This post ran in 2017 and the last time I looked, the Four Corners is still a Roadrunner cartoon landscape. Here, I explain, at least in part, why.

Flying through Monument Valley on the Arizona/Utah border recently, I was crammed into an old and slow Cessna 147 taildragger. Light filtered through the smoke of distant wildfires. It felt like looking through antique glass at a country of stone giants. We’d arrived at the last blink of this particular landscape, buttes shipwrecked alone in the desert, thin memories of mesas and canyons blown out by erosion.

When I posted the above photo on social media, one of the LWON writers commented that the landmarks look like volcanic necks, which are the hardened insides of volcanoes left when the rest of the land has eroded away. When I said no, this is straight sandstone erosion and not a cluster of exposed volcanic guts, she said prove it.

The simplest proof is stratigraphic. The rocks making up Monument Valley are all sandstone, siltstone, and other Paleozoic sedimentary layers stacked on each other; no volcanics. Volcanic necks are in the region, like Agathla Peak standing like a ragged castle just outside of Monument Valley, or Shiprock across the way in New Mexico. Besides these occasional volcanic necks, the landscape for hundreds of miles is made of sedimentary rock. Shinarump, Moenkopi, De Chelly, and Organ Rock formations give Monument Valley its iconic cliff-step outline. Differential erosion looks like pages in a book, one page 700 feet thick forming a dauntless wall, another page tattered with boulders forming a slope.

Though hard when it falls on you, this rock is relatively soft as rocks go. Some of the towers have eroded back to popsicle sticks of their former selves. They survive not because they’re harder than the rest, but because something has to be last to go. They stand in aprons of their own fallen debris.

As a handy reference, a mesa is wider than it is tall and a butte taller than it is wide. A butte is what a mesa becomes as erosion whittles it down. Monument Valley has mostly buttes. Many look as if they’re standing on their toes, like the Totem Pole, 450 feet tall depending on where you start, and 30 feet wide; or flat-footed and stout Merrick Butte, nearly a thousand feet tall with a footprint of about 15 acres.

We’d been flying over a museum of erosion for days on the Colorado Plateau, a 140,000-square-mile blister rising out of the Four Corners states. The picture below from the flight is the snakelike course of the Escalante River where it has been drown by Lake Powell. The actual floor of the canyon is hundreds of feet below the water’s surface. Note how the natural meander of a small river has set itself into solid rock. The land responds eagerly and with only mild resistance to forces of erosion. That causes this sort of formation, weather and stone perfectly matched.

Monument Valley has been gently rising over millions of years, part of what is called the Monument Upwarp, a platform of elevated earth that rises from here to about 40 miles into Utah. Layered by sheets of thick sedimentary rock, the ground in this upwarp is made of fairly rigid planes. When the planes are pushed up by tectonic forces, they crack. They are too heavy and expansive to stay together; they have to break. Cracks spread as rains run down through them. Gullies form, and then canyons. Rain washes half of everything out, sending it eventually into the San Juan River along Oljeto Wash about 20 miles northwest of Monument Valley, acting as a waste removal service keeping the monuments from drowning in their own debris.

The San Juan enters the nearby Colorado River which, before the age of giant dams, used to carry about 90 million tons of sediment per year. That sediment load is the land washing away.

What doesn’t go with water goes with wind. Fine sand, the glue of this landscape, flies with every storm. What’s left behind is a land falling apart along fracture line defined by breaking sheets of rock.

Flying over Monument Valley, I could hardly say anything intelligent over the headset, any more than, look at that and oh my god. Smoke added a ghostly veil, making the erosion seem all the more sublime. The enormous shapes of the earth became footprints of some ancient walking god, which is how this landscape was made.

Photos by Craig Childs

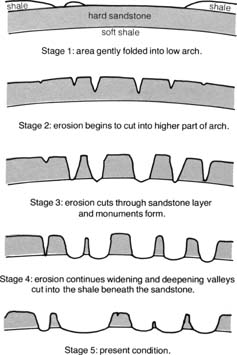

Illustration: Schematic Representation of the Evolution of Typical Landforms in the Navajo Section of the Colorado Plateau (W. L. Stokes, 1973)

I consider the argument for sedimentary, i.e., non-igneous, structures to be thoroughly and credibly backed by evidence, I withdraw my challenge in re: volcanic necks, and I’ll never question Craig again.

But there are some volcanic necks there. Shipwreck and the one north of Kayanta that I keep calling “Agatha”…

Shiprock, right? I knew there were volcanic necks around there, which I why I assumed Craig’s weird towers were volcanic. Instead of straight erosion on flat land. I love that, when I’m completely wrong about something.

You should question me every time, Ann, for I am wholly questionable.

Like!

This was a GREAT explanation. I agree very thorough. And the graphics were right on. I will say I always thought this landscape was the result of the movement of underlying salt that caused crack in the above rock where the erosionally expanding cracks formed a landscape seen in Arches NP. I am happy to be enlightened.

After spending a lifetime or two crawling around this area, it must have been mind-blowing to see it all from the air. Thank you for sharing it with us.

Well and cogently stated. This country is beautiful from every aspect.

Wonderful writing. The smoke makes it look like a photo from a moon of Jupiter.

Bellissimo post, molto esauriente. Grazie

Thank god you are not invoking the dreaded ‘electric geology’ hallucination to this :).

I love this quote “Differential erosion looks like pages in a book, one page 700 feet thick forming a dauntless wall, another page tattered with boulders forming a slope.” And it turns out having a geologist father spout science on every family trip has paid off – I knew it was a sedimentary basin. 🙂

Great description and explanation.

You mentioned the area experiencing uplift. I am used to the concept of isostatic readjustment causing uplift in Ireland and Britain as a result of the melting of the ice age ice sheets removing enormous weight from the land. What is the cause of the uplift in Monument Valley? I can see removal of the sandstone having an effect, but were there other influences that started the uplift?

Nice article and photos!

Peter, this uplift comes from the collision of the Pacific and North American plates and the tectonic crunch from California to the Front Range of Colorado.

Glad to see this article and your subsequent replies to questions. Thanks Craig

As a geologist/photographer, I am delighted by this article. The multitude of physical processes occurring simultaneously and in harmony has created one of my favorite landscapes on Earth. It’s a geologic marvel.

thank you for a great explanation regarding one of my most favorite places. and for a good reminder that there are always way too many unanswered questions and way too many unquestioned answers. the last time i was there, way too long ago, a howling wind storm carrying tons of sand absolutely amazed me. i thought perhaps the entire valley was heading for ‘kansas’, hoping to ‘meet up with dorothy’. i wondered where did all the sand go. a very much ‘amateur’ geologist. pete

Nice read-thanks… especially since absorbing your performance(?) at The Blue Sage the other night. Geology can be fun!

Like Devils Thumb near Delta, which I always thought was rock until geologist D’s e Noe took us up there and explained the formatiion.

I can’t remember a more visceral experience than seeing Shiprock emerge from behind a rise as we drove from Cortez to Farmington. It loomed up, huge and powerful, the perspective obscuring distance. And again, as we drove through Farmington and turned to face back toward Shiprock, it loomed up like a leviathan from the sea. Distance is warped again which makes the rock that much more magical. No wonder it is held sacred. It expands the heart and mind with its presence. Thank you for this essay, Craig. When we homeschool my grandchildren, I want to use your books to open the doors to exploration. Your perspective on landscapes and culture are beyond the literature. You have a way of distilling others’ findings and knowledge into poetic access for the lay reader.

Full disclosure. I have been waiting for a Craig post to ask an unrelated question. I hope that’s ok. I would like to know if you are familiar with the Wingmaker/Ancient Arrow site somewhere near Chaco. Is it real?

Hey Allison, fine to ask, and though I know a lot of sites around Chaco, I don’t know the Wingmaker/Ancient Arrow site. Sounds like it might be more in liminal space than archaeological.

Thank you for reply. It definitely could be liminal, but the history is weird. It came to light in late 90’s on a website that was then altered. But somebody kept track and the original art, poetry and philosophy still exist. Fair warning. This is a reality breaking thing and I understand if the rational brain says no way. But the truth is that our understanding of reality is about to get updated and we all have to come to grips with that fact. The philosophy here may help with that. Also please read the glossary and note the specific year references. You have to keep in mind this website was recovered by the way back machine so the date references are future looking no matter what you believe about the time capsule aspect of this. My sincere hope is that this makes you curious and kindles your imagination.

https://www.wingmakers.us/wingmakersorig/wingmakers/ancient_arrow_project.shtml

Thank you for your great writing and I hope you have fun with this.