Next week is Shark Week, which means that we at the Last Word will be spending the week specifically not talking about sharks. Instead, we will scour the globe for far more dangerous and adorable critters in a yearly tradition called Snark Week.

And while I might argue that Snark Week is a far bigger deal than Shark Week, I’ll allow that a few people will also be watching shark documentaries starting on Sunday.

Like any passionate shark lover, I once adored shark flicks. The brave scientist pressing into the unknown, the cool gadgets, the thrashing of a hippo-sized toothy fish from the deep that quickly returns from whence it came – this is the stuff of obsession for any nerdy 11-year-old kid.

But today, most of these movies make me want to wretch. It’s not just the puffy-chest posing and the gravely-voiced narrators, it’s the whole vibe. Sharks on Shark Week aren’t really animals anymore, they’re props. And increasingly the stars aren’t scientists, they’re stuntmen like Dickie Chivell, who gets on surfboard-like things to see if he can tempt a white shark to bite him or Micheal Phelps, who … I honestly don’t know what the hell that guy has to do with sharks.

This isn’t David Attenborough, this is Jackass. Danger porn.

Proponents of Shark Week claim that the program helps bring awareness to sharks and promotes conservation. But let’s get real, no one walks away from Shark Week saying, “Wow, I really want to donate to conservation efforts.”

Proponents of Shark Week claim that the program helps bring awareness to sharks and promotes conservation. But let’s get real, no one walks away from Shark Week saying, “Wow, I really want to donate to conservation efforts.”

Twenty-nine million people tune in to Shark Week with an average of 2 million per episode and yet no conservation NGO I know of sees a bump in donations. If anything, shark populations have plummeted during the 27 years Shark Week has been on the air.

But the most annoying part of Shark Week is all the faux science. I don’t mean megalodons and mermaids, I mean the illusion that we know anything about these animals.

Take my – and everybody’s – favorite shark, the great white.* Let’s make a list of what we know: Weight, length, gathering areas, eating preferences, and favorite angles of attack. We know a fair bit about their physiology and a bit about their role in the ecosystem.

What we don’t know: Whether it migrates (with the possible exception of California), how long it lives, how old it is when it reaches maturity or even how many there are. No one has seen them mate or give birth, and we only have the faintest idea where this might happen.

What we don’t know: Whether it migrates (with the possible exception of California), how long it lives, how old it is when it reaches maturity or even how many there are. No one has seen them mate or give birth, and we only have the faintest idea where this might happen.

Which is shameful considering how much money the entertainment industry makes on great white sharks. At the beginning of every shark documentary there should be a disclaimer: “No one featured in this film has the money to do even the basic science on these potentially endangered animals but enjoy the footage of one chewing on a cage.”

If I sound like I’m railing against shark scientists, I’m not. While researching a story for National Geographic last year, I posed these criticism to several experts, some of whom spend a fair amount of time on TV and got quite offended. But a few good-natured ones went along with me. The conversation would go something like this:

“Why have none of you people ever seen great whites mate?”

“Well, it’s really hard.”

“You are an expert! Figure something out.”

“Any ideas?”

“Send a submersible into the great white shark cafe.”

“And do what? It’s like twice the size of California. What, are we just supposed to sit there and hope some amorous sharks swim by?”

“Then put a video camera on them.”

“Batteries don’t last that long. Plus, they stay deep and there isn’t much light. These aren’t dolphins, you know.”

Eventually, I come up with an elaborate scheme involving helicopters launched from aircraft carriers and armed with ROVs, at which point the scientist hangs up and goes back to his/her windowless cubicle in the basement of a university biology department.

Eventually, I come up with an elaborate scheme involving helicopters launched from aircraft carriers and armed with ROVs, at which point the scientist hangs up and goes back to his/her windowless cubicle in the basement of a university biology department.

And it’s not just white sharks. I heard a story from a whale shark researcher about a team that managed to tag a whale shark and track it for nine days. At the time, this was a record and they collected incredible data showing the animal was actually following the tides up and down the coast.

Until one clever scientist realized that the animal had ditched the tracking device the first day and it was just floating somewhere at the surface.

The point is that shark research is very hard because they 1) travel long distances, 2) don’t need to surface to breathe and 3) aren’t really that numerous. Also, some of them like to rub themselves on the sea floor to remove trackers. Still, I would argue that we know a lot more about the far-ranging carnivorous tuna because there is a massive industry willing to pony up for research on them.

So when is the Discovery Channel going to start paying back the world’s shark communities for the fortune they’ve made over the years? I don’t mean painting murals in the inner city, creating communications strategies that involve making more films or creating a “movement” to someday help the oceans. And I certainly don’t mean loaning boats to scientists as long as they agree to have cameras shoved in their faces.

I mean something they can’t attach their name to and use as a promotional tool. I mean cold, hard cash to answer the most important scientific questions surrounding their favorite mascots. So that next time a scientist has to put up with an obnoxious journalist like me, they can have a little more to tell them.

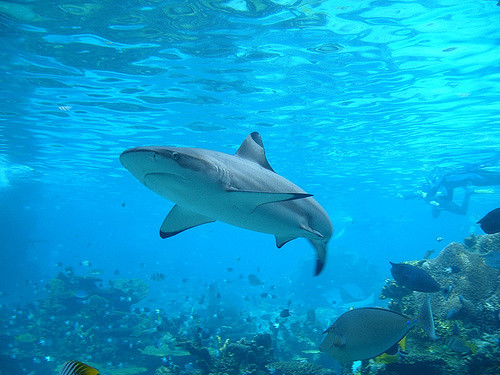

Photo Credit: Erik Vance, Jeff Kubina, Malkusch Markus, Ryan Espanto

* I know a lot of people like to drop the “great.” But to me the great white shark will always be great. After all, without “great,” it’s just a blue heron, a crested newt and an egret. Animals should be great.

Absolutely spot on.

I re-posted this on my FB. Thank you for writing it so I didn’t have to.