I’d been reading a book by Colm Tóibín called House of Names. The house is the House of Atreus; Tóibín explained through a character why he substituted “names,” but I didn’t understand it. He took the story pretty faithfully from the plays of Sophocles, Aeschylus, and Euripedes about one or all members of the family. The family was dreadful, every one of them, and Tóibín made each individual dreadfulness understandable, as did the original Greek playwrights. The family is soaked in its own blood, generation after generation; crime begets murder which bets revenge killing and more revenge killing and revenge killing that never stops. The translator of the Greek plays, Robert Fagles, calls it an “inherited infection.”

Somewhere in the middle, I started to wonder about the strange discrepancy between these revenge-addled murderers and the rational, educated ancient Greeks who were the foundation of Western civilization; who founded much of our sculpture, architecture, philosophy, literature, math, and science; and who told these terrible stories over and over.

You probably know the story of the House of Atreus but I’ll tell you again anyway. The story begins with meddling gods — who are, compared to the humans, unconvincing and uninteresting,Tóibín leaves them out completely and I will too – and moves on to misbehaving humans who are clearly cursed, whose blood is made of desire for love and power and revenge, and because the desire is in the blood, it’s inexorable.

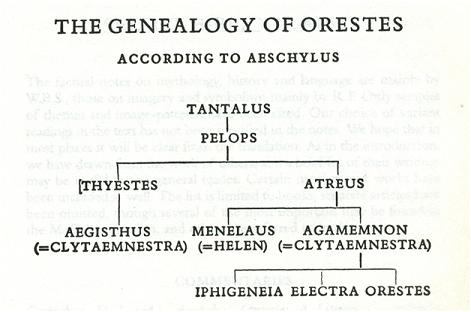

Atreus had a brother named Thyestes who was sleeping with Atreus’s wife. Atreus killed Thyestes’ children, cooked them, and served them to Thyestes. Thyestes had another son, Aegisthus, who grew up to sleep with Clytemnestra, the wife of Atreus’s son, Agamemnon. Agamemnon for one reason or another – maybe because his navy was becalmed and the gods needed a sacrifice before they’d send wind – sacrificed Iphigenia, his daughter with Clytemnestra. Clytemnestra, with Aegisthus’s help, murdered Agamemnon. Agamemenon and Clytemestra’s son, Iphigenia’s brother, Orestes, at the urging of his other sister, Electra, murdered Clytemnestra. Toíbín ends his book with Orestes agreeing to give up his claim to kingship and live out his life in quiet domesticity

Atreus had a brother named Thyestes who was sleeping with Atreus’s wife. Atreus killed Thyestes’ children, cooked them, and served them to Thyestes. Thyestes had another son, Aegisthus, who grew up to sleep with Clytemnestra, the wife of Atreus’s son, Agamemnon. Agamemnon for one reason or another – maybe because his navy was becalmed and the gods needed a sacrifice before they’d send wind – sacrificed Iphigenia, his daughter with Clytemnestra. Clytemnestra, with Aegisthus’s help, murdered Agamemnon. Agamemenon and Clytemestra’s son, Iphigenia’s brother, Orestes, at the urging of his other sister, Electra, murdered Clytemnestra. Toíbín ends his book with Orestes agreeing to give up his claim to kingship and live out his life in quiet domesticity

What to make of this? An eye for an eye, kill and be killed. It’s thoroughly human, it’s certainly not civilized, and the Greeks who wrote and watched these plays were nothing if not civilized. But a lot of their plays have the same story: someone does something wrong, someone gets revenge, the children inherit the wrong and avenge the revenge, and so do their own children. I can think of a couple of reasons for this.

One is that it’s true. We call it different things today – genetics, environmental influences, sociological tribalism — but it still plays out not only obviously in organized crime and the murder code of the inner cities, but also in every division we’ve got: religious, political, economic, cultural, educational. It’s what we do. We live in families, and that’s the source of both our loveliest virtues and our most shameful vices.

Another is that the stories are of people and acts so terrible that nothing good can come of them. That’s so obvious. Nobody’s going to live happily ever after here, not Agamemnon, not Clytemnestra, not Electra and Orestes. In Aeschylus’s play, Orestes leaves his home, hounded by the Furies, and wanders frightened and guilty until the gods and the Furies hold a trial to balance justice with revenge. Orestes is freed from the Furies, but nobody’s forgetting his mother’s death,

Fagles makes a lot of this balance between the gods and the Furies, and of Aeschylus’s real ending, which turns the Furies, the Erinyes, into the Eumenides, the Good Ones. (I find Fagles a little hard to follow, though his translations are vivid.) But maybe the ancient Greeks told these stories as a way for intelligent, perceptive, civilized people to remember the lethality of their heritage, to not forget that the alternative to law and rationality is real, alive, and always present.

________

Illustrations from Alfred Church, Stories from the Greek Tragedians, 1897, via Project Gutenberg and Wikimedia Commons

There’s a different interpretation of all this stuff that’s articulated by Roberto Calasso in _Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony_. Thyestes, guided by advice from the Oracle at Delphi, rapes his daughter, who, pregnant, goes on to marry Atreus (Aegisthus, Thyestes’ biological son, is raised as Atreus’ son). In this view the point is that there _is_ no house of Atreus — his descendants are all Thyestes’, and the whole thing collapses in on itself.