Last night I ran through quotes in my new book manuscript, making sure they were all amply annotated, meaning I spelled the names right. There were a lot of women in this run. For a book on the Ice Age and paleo sciences, mostly archaeology and paleontology, I’d had no trouble finding female researchers to write about and interview.

Last night I ran through quotes in my new book manuscript, making sure they were all amply annotated, meaning I spelled the names right. There were a lot of women in this run. For a book on the Ice Age and paleo sciences, mostly archaeology and paleontology, I’d had no trouble finding female researchers to write about and interview.

My previous book, dealing with climate and earth sciences, was sometimes a struggle to get female quotes. Often the woman was the second, third, or fourth name on a paper. I’d call and she’d ask why I was talking to her instead of the first name, the principal investigator. If I said it was because I was trying to keep a balance of male and female researchers, there was usually an awkward silence as we both tried to figure out what that really meant.

My research between different books is not a reliable statistic. Maybe I was reading the wrong papers. More women in paleo sciences, especially paleontology, fewer in earth sciences and climates, is above my pay grade to fact check. But it was something I noticed anecdotally.

In paleontology, especially Pleistocene, women were at the top of more than half the papers I read. There was a group that over the years I came to call the Bone Women, osteologist Phd’s working with Pleistocene fauna. We’d get together and cover lab tables with skulls, unhinging sabertooth cat jaws, sticking our heads in the rib cages of giant sloths. It felt like we were right down in the heart of a creation story.

For climate change, astronomy, geosciences, on the other hand, I somehow found myself in many offices of men.

Is this divide among disciplines real? The answer may be somewhere in this 330-page document, “Meta-Analysis of Gender and Science Research” by the European Commission, but I’ve got to pick up kids from school and I can’t read the report right now.

Here’s another anecdotal bit of gender research I’ve done. I used to work in the Grand Canyon, either on assignment on a river trip or swamping, running baggage in rafts, taking on big rapids poorly, which is why I had the gear and not the passengers. Something I noticed in those years was that women on the oars through a Class V rapid, the biggest water in North America, were invariably quieter than their male counterparts. I don’t mean quieter by voice. Both men and women tended to only make a small, barely audible gasp, oars in hand as they plunged down the 17-foot-drop of Lava Falls, but damn if the oar locks didn’t clack and screech in certain hands.

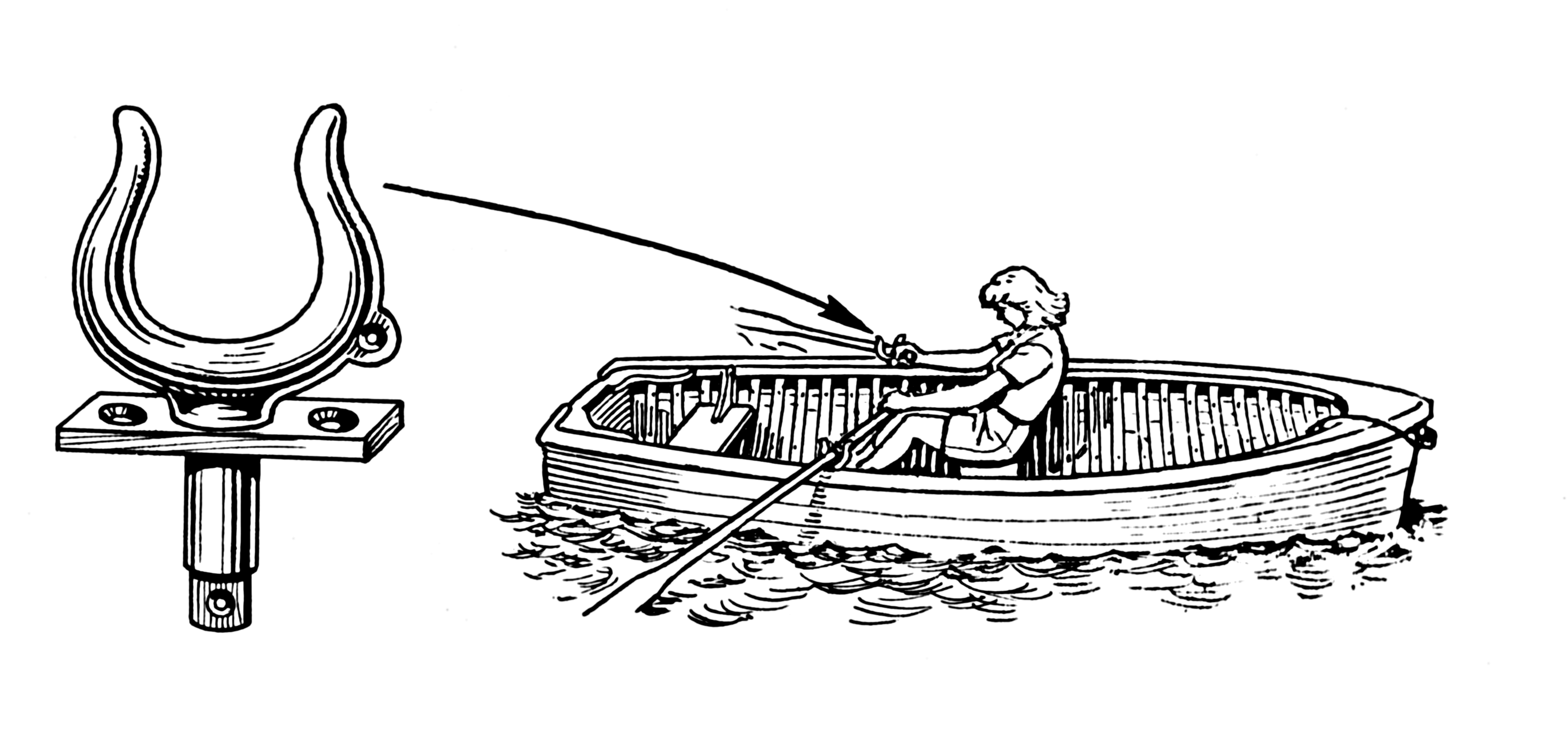

Oar locks are brass fittings, partly-closed Us that hold the oar, giving it a fulcrum for plunging blades into the water. Men banged the hell out of the things. In the fury of a rapid, 15-foot standing waves breaking overhead, you could hear the wild crack of the oar locks, forward and back strokes, full-body presses, a couple hundred pounds of force against solid water.

Women often lifted their oars from the water, reading, watching, touching lightly before driving all their weight. It was a different understanding of water, not to overcome it, but to run with it.

I’m writing stereotypically, of course. Sexist for all I know. But I witnessed a difference in the Grand Canyon, just like I do from one book to the next as I interview and read the work of scientists.

The oar locks of women were almost invariably finessed, while men humped those things like barbarians, which may get a name closer to the top of the paper in traditionally male dominated fields, which river guiding is (currently Grand Canyon National Park has suspended its river ranger program for Title IX issues). In the end, the work was the same. It was good. Some flipped, some didn’t. In the end, the guides, the scientists, were people who knew the terrain and handled it well.

The difference may be that among guides, the sound of oar locks was a personal demonstration. It had nothing to do with hierarchy or undermined expectations. It was raw expression of body and mind. Having your name a few notches down from the top on a paper is not necessarily choice. It is not an expression of body and mind, but of how a system functions, or dysfunctions.

I don’t have a conclusion from this. Both of these gender incidents caught my eye, and I thought, before I pick up the kids, I should say something.

Image: Wikipedia

Thank you for writing this, Craig. It is a struggle, both with oarlocks and academia, for women. My take is that women, given less strength, try to figure out a way to work with something rather than to wrestle it into submission.

An excellent work!

I’m gonna take this oar lock metaphor into my day with me.Thanks, friend. You are always the exception when I roll my eyes, shake my head and mutter, “dudes!?!”

Thank you for paying attention, to being thoughtful and noticing the subtleties. Love the rhythm of this, “but damn if the oar locks didn’t clack and screech in certain hands.” Reminds me of Maybelle in “Forced Branches.”

I know the percentage of women in astronomy — or at least, I know where to find it but I have to pick up the kids, no I don’t, I have to get back to work — but my own anecdotal observation that some subfields of astronomy have more women than others — especially stars, women tend to study stars. With notable exceptions.

I have been a river guide for thirty years, and the best boat drivers I knew were women. The very best, on the Grand, was a woman of slight build from Big Water, who just made it look easy, because she didn’t have the muscle to power through rapids — she had to out-think them.

You perceived a rare and profound difference. ” It was a different understanding of water, not to overcome it, but to run with it.” Yes exactly!

I have degrees in astrophysics and geophysics. My own observations are that there are far more women in senior scientist positions in the latter than the former. But that’s just my limited view, of course.

Interestingly when I was studying (15 yrs ago), I went to a symposium on gender in science. There is research out there on the peer review process and how papers fare when the authors are obviously male, obviously female, and obscured. If I recall correctly, for this research the same papers were submitted under different naming schemes. Papers with male and indeterminate names fared better in the peer review process than those with female names. Most interesting to me was that the researchers also examined whether the sex of the reviewer mattered. What they found was that when women review papers by other women, they are more harsh than when the review papers by men or indeterminate. The explanation offered by the authors was that women who “had arrived” in the sciences were holding the bar high (consciously or sub-consciously) in order to combat the *perception* that women did sub-standard work. And this was a reflection of the harsh environment created around them by the men they worked with.

I learned from some of the best but the most important points were as follows:

Always be looking downriver and watch your drift

You don’t need to miss “it” (rock, hole, eddy line…) by a mile, only an inch (refer to first point)

Let the river do the work

This reminded me of the essay Two Women, Three Men on a Raft, by Robert Schrank. FROM THE MAY–JUNE 1994 ISSUE of Harvard Business Review. Orig 1977.

My observations from a nonacademic perspective is historical. Over the past 200+ years, correlated to the Industrial Revolution, through natural selection, and self-domestication each generation has redefined gender roles. This is certainly true with academia, which was once a male bastion, is now majority female. We (male/female) keep redefining ourselves with each generation. If we address these changes as changes with the objectivity of critique, and not the subjectivity of criticism we will better achieve gender equality (which seems to be the gradient direction) through conscious selection of preferred phenotype qualities. As mothers were the paradigm of parenting, and fathers relegated these roles are also changing reversing the parental hierarchy. Navigating whitewater is reading the water’s laminar flow, and the turbulence from obstacle interference. It requires both going with the flow (the finesse of quiet oarlocks) to shoot the rapids, and resisting it (the battle of forces with noisy oarlocks) to not get sucked into a hole each is to avoid disaster. Knowing when, and where to apply either comes with experience. And each has its place. As do we, and we will change in response to social paradigm changes. Hold on; it’s going to be a bumpy ride.

I have learned more about handling a boat in big water through watching small women row than I ever have from watching the big boys. Women naturally employ an economy of motion that doesn’t waste a thing. The water moves and you must learn to dance with it.