On Friday, January 27th, Donald Trump signed an executive order banning people from seven countries from entering the United States. And in the wake of that executive order, there have been a continuos stream of reports that people trying to enter the United States (whether from those countries or not) have been subjected to a variety of questions and searches.

One Canadian student with family ties to Morocco says he was asked about whether he went to mosques, and which ones specifically, and was asked to turn over his phone and passwords. A NASA scientist was detained at the border and says he was told he would not be released unless he gave the border guards access to his phone. Another Canadian woman was turned away from the border after the police reportedly questioned her about her Muslim faith and looked through her phone for about an hour.

Over the past few weeks I’ve seen story after story about how to secure your digital information online, and others wondering if it was even possible. I’ve also had a lot of friends asking me, both rhetorically and literally if they plan to try and travel outside the United States, what the rules are about this kind of thing. Can the US Customs and Border Patrol demand your phone’s contents? Your social media information? Your passwords?

All this got me thinking about something that a legal scholar told me a while back, about how the law treats phones. I preface all of this saying that I am very, very, very much not a lawyer and this should not be construed as legal advice of any kind. I just thought it was interesting.

The first thing to get out of the way is that the rules at the border are slightly different than the rules anywhere else. The border is considered a “zone of reduced privacy expectation.” In 2014, the Supreme Court decided that police needed a warrant to search the contents of your cell phone. But that doesn’t necessarily apply to the border, which remains in a “legal limbo” where individual officers can kind of operate however they see fit. Until there’s some kind of legal precedent specific to the border, there’s no real clear rule.

But what about your protection from self-incrimination? Generally, courts draw a line between what they call “contents of the mind” and “tangible” bodily evidence like fingerprints or blood or DNA. That tangible evidence isn’t protected by the 5th amendment — so with a warrant you can get that stuff. But the “contents of the mind” stuff, that’s protected. So when it comes to your cell phone, your fingerprint to unlock it isn’t protected in court, but the password that lives in your mind is. (This is one reason to nix the fingerprint unlock and stick with the memorized passcode.)

But then once they get inside the phone, it’s the Wild West legally. When I was doing some reporting for a story about a lab that was trying to 3D print replicas of a dead man’s fingers so the police could access his phone, I wound up talking to a guy named Bryan Choi, a researcher who focuses on security, law and technology.

Choi has argued that phones should be considered extensions of our minds and should be protected under the Fifth Amendment (protection against self-incrimination) and not just the Fourth Amendment (protection against illegal search and seizure). He argues that cell phones are unlike almost anything else we own.

“We offload so many of our personal thoughts, moments, tics, and habits to our cellphones,” he said in his email. “Having those contents aired in court feels like having your innermost thoughts extracted and spilled unwillingly in public.”

So Choi argues that our phones are objects unlike almost anything else we’ve ever had. He says that they’re more like prosthetic limbs than they are like wallets or even notebooks. “Our data is deeply imbued with our personhood, and leaving it unguarded leaves our persons unprotected by the Constitution,” he wrote in his paper on the intersection between the fourth and fifth amendments.

Choi argues that evidence the police pull from your phone isn’t like having a friend testify against you. And it’s not like having a bloody shirt or glove presented as evidence. It’s another thing entirely. It would be like someone was able to scan your brain and read your thoughts, and then use those thoughts against you. If we had machines that could actually read minds, and that could extract memories to play for the court, that would be more akin to our cell phones contents than anything else. And Choi thinks that should be protected, in the same way that the memories contained within our fleshy brains are protected.

And this brings us to some questions too about the future search of cell phones. Here’s an analogy: when the police get a warrant to search a house, they often have to specify which parts of the home they want to search, and justify why they want access to those rooms. And if they find evidence in parts of the home they weren’t supposed to be in, that evidence can’t be used in court. So if the police do get a warrant to search a cell phone, should that warrant be limited to certain apps or sections of the phone? Will future warrants be specifically for the photo albums, but exclude the contents of apps like Tinder or WhatsApp?

Or, to bring it back to the border situation, will border guards be given permission to look at your Twitter and Facebook profiles, but not, say, read your emails or text messages? Which rooms of your digital house are they allowed to go into without a warrant? Nobody knows, this is uncharted territory. But I suspect, with all the high profile searches happening right now, we might see a few of these cases in court soon.

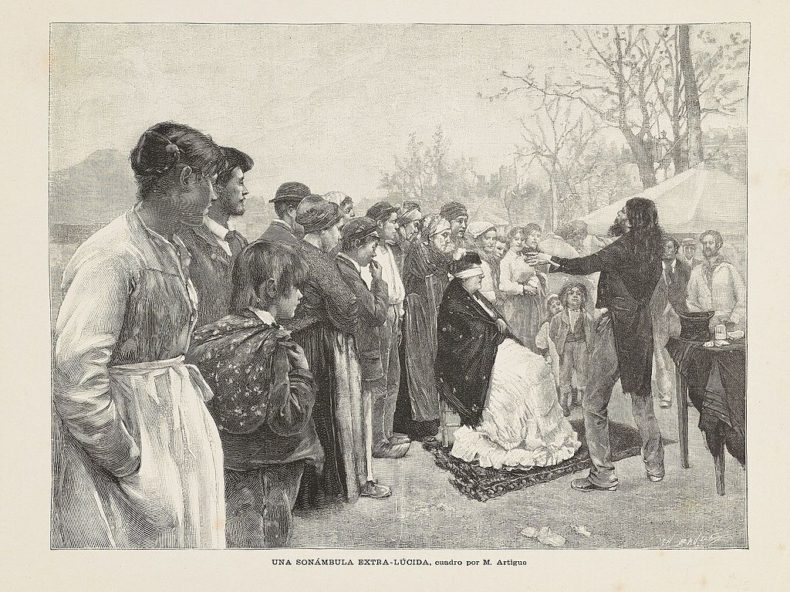

Top image: A pair of mind-readers performing among a group of villagers. Wood engraving after Artigue. Wellcome Images.

Huh–interesting! What about a journal or private diary? That seems very cell-phone like in this case.