Early Monday morning, a fireball lit up the night sky over Wisconsin. For a just a second, dark became light. And then there was an explosion followed by a terrifying sonic boom.

Loretta Brockmeier, a resident of Random Lake, Wisconsin, a town about 40 minutes north of Milwaukee, got up to use the bathroom and happened to catch a glimpse of the blaze, “a bright green flash that lit up the outside like the sun,” she wrote on Facebook. Brockmeier went to the window to see if she could puzzle out the cause, but nothing seemed amiss. A minute later, she heard a thunderous blast followed by rumbling. It sounded “like a boulder hitting the roof and rolling down the side,” she wrote.

Meanwhile, I was fast asleep. But I heard the news the next morning on Wisconsin Public Radio. And it was the term “fireball” that gave me pause. Fireball sounds like the kind of thing that might precede the apocalypse. But the reporter offered no explanation. No definition. As if fireballs are commonplace.

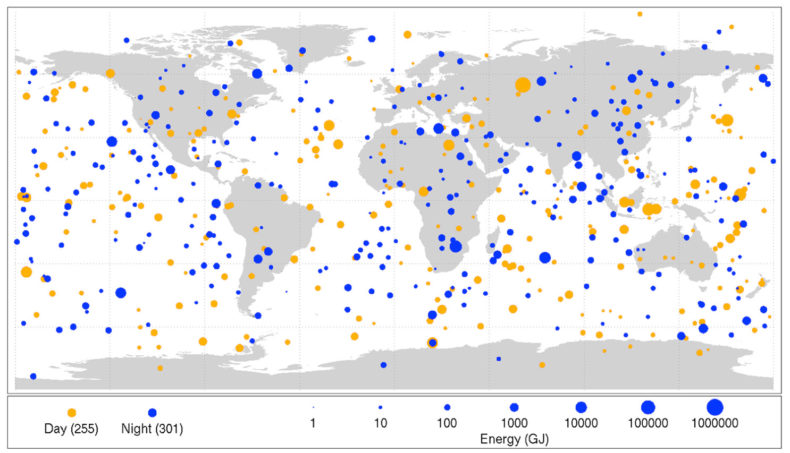

That’s because they are. According to NASA’s Center for Near Earth Object Studies, since 1988 there have been 699 fireballs over the US alone. That’s roughly 30 blazing balls streaking through our atmosphere each year.

What exactly is a fireball? Let me walk you through some terminology. Asteroids are large rocks orbiting the sun. Much smaller rocks or rock fragments are called meteoroids. When an asteroid or meteoroid enters Earth’s atmosphere and creates a visible path as it heats up, it becomes a meteor (aka a shooting star). A fireball or bolide is an exceptionally bright meteor, often one that explodes.

Pretty! But also terrifying, because these burning hunks of rock don’t always vaporize. The meteoroid that blazed across the sky at 1:30am on Monday likely landed in Lake Michigan. (A chunk of asteroid or meteoroid that survives the journey through Earth’s atmosphere and hits the planet’s surface becomes a meteorite.) The meteoroid was about the size of a minivan when it entered the atmosphere. The meteorite that splashed down was about the size of a lunch box.

Almost exactly four years ago, a much larger fireball, an 11,000-ton chunk of rock 59 feet wide, exploded about 15 miles above the Ural Mountains in Russia. According to NASA, the blast released more than 30 times the energy from the Hiroshima bomb. The explosion destroyed buildings and shattered windows, injuring more than 1,000 people.

There’s footage of this event. Lots of footage. And what I find striking is the total lack of panic, at least initially. Many of the videos were shot in moving cars. The fireball blazes in, explodes, and blazes out of the shot. The cars keep moving. Nobody freaks out until the sound arrives.

https://youtu.be/TdWZwC_7s08

For example, look at this video of a judo class. Kids are fighting and falling down. And then the window gets bright. Really bright. And the kids keep falling and fighting. No one even glances at the window. They don’t seem to register that something momentous has occurred until the blast shatters glass. And even then two of them (teachers?) just walk slowly to the other side of the room.

Perhaps this wasn’t their first fireball. According to NASA, more than 100 tons of meteors pummel Earth’s atmosphere each day. Rocks smaller than about 80 feet in diameter don’t pose much risk. They typically burn up before hitting the planet’s surface. The bigger ones, however, are more worrisome. Some, like the Russian fireball, might only cause local damage. But NASA scientists estimate that any asteroid with a diameter larger than half a mile could have global effects. That’s why the agency established the Planetary Defense Coordination Office.

Planetary defense sounds bad ass. But don’t get too excited. Asteroids travel at 12 miles per second. We don’t have a weapon powerful enough to destroy them before impact. But with decades of warning, we might be able prevent a collision. One option is to place a spacecraft in the asteroid’s path. The asteroid would ram the spacecraft, slow down, and (fingers crossed) deviate from its original course. This is called a kinetic impactor. A spacecraft could also be used as a gravity tractor. If the craft flew next to the asteroid for years or decades its weak gravitational pull might tug the asteroid off course. Explosives might also be able to change an asteroid’s trajectory. None of these strategies are ready to be deployed.

And it’s unclear whether any of these strategies would actually work for the largest asteroids. The one that contributed to the demise of the dinosaurs was six miles wide. The impact ripped an enormous hole in the planet’s crust, triggering violent earthquakes and 300-foot-high tsunami waves.

Imagine what a fireball that would have been! Or don’t. Because maybe you want to sleep tonight.

***

Top image is a screenshot from the UW Space Science and Engineering building video

The map is from NASA’s Near Earth Object Observations Program

Fascinating! And alarming. Thanks for the breakdown of terminology, very informative.