My friend, I’ll call her Anna, is dying today. She was dying yesterday, too, and tomorrow she’ll be even closer to death than today. That’s true of all of us, I suppose, but she’s on the fast track: Her gut is so clogged up with cancer that there’s nothing left to do for her but pump her full of powerful pain meds and wait. She is thirty-something and has a gentle husband and a daughter not yet four.

A couple of weeks ago Anna’s gut seized up like an engine drained of oil. Normally, smooth-muscle contractions known as peristalsis propel food in waves through the digestive tract. In Anna’s ravaged body that process, finally, shut down. She’d already endured the excruciating pain of intestinal blockage; her life had more or less become a series of agonizing bodily failures. To “cure” her this time meant abdominal surgery, her fourth since her original cancer diagnosis. The surgeon had to divert the stopped-up bowel by installing a tube to the outside with a pouch that would sit against her abdomen to catch waste. When I hugged her, she held back: “I’m disgusting,” she said, and averted her red-rimmed eyes. “This is such a nightmare.”

My poor friend had already been through enough misery, including round after round of chemotherapy. Chemo seems so barbaric, doesn’t it? A toxic mixture dripped into the veins to beat the crap out of cells—but it doesn’t know sick cells from healthy ones and so pummels indiscriminately. You get horrible side effects and no promise of a true cure. Researchers are starting to use more targeted therapies formulated exactly for an individual patient, but such drugs haven’t been terribly effective on colorectal-cancer patients. Still, Anna tried a combination of therapies for a short time, just in case. But no matter which treatment, one side effect was to exhaust her such that she could barely lift her daughter into her arms.

Her oncologist had been aggressive with the chemo, and early on, when the cancer was contained, surgery plus chemo had given Anna a stretch of cancer-free months. But the disease soon roared back to life, bigger and nastier than before. The doc still insisted the tumors were shrinking, or at least holding steady. Anna, rail-thin except for her lower legs—so heavy with fluid that I had to lift each one onto the sofa for her—told me that the doc wanted to restart chemo as soon as the new surgical wounds healed.

Her surgeon seemed exasperated by this plan. “I’ve been in there; I’ve seen the cancer,” she told Anna after surgery #4. “It’s all over the place. I’m not sure why he’s so hopeful.”

Maybe those weren’t the surgeon’s exact words, but her honesty landed a powerful blow. Anna hadn’t yet lost all hope…but I suspect she did then.

And that’s when her body, like her surgeon, told her the truth. It stopped healing. The surgical wounds continued to seep, refusing to scab over. Her pain worsened. She ended up back in the ER with complications. Her immune system, like the medical establishment, had run out of tools to try. She would die soon, but what soon meant was distressingly unknowable.

At about the same time that Anna’s body gave up, an older neighbor of my aunt’s out in California decided she’d had enough. She’d been ill for a very long time and was weary of fighting. She picked a date, arranged for light snacks, and invited her friends to come by for her farewell party. On the designated afternoon, a nurse helped her put on her favorite dress, scarf, and jewelry and apply makeup. She opened the door to her guests looking rather elegant. They spent a few of hours milling around her bed, laughing and telling stories, holding her hands and saying goodbye. When the time was right, the woman nodded to her doctor, who deactivated the pacemaker that was pumping blood to her heart. The woman died quietly with friends close, exactly the way she’d intended.

Currently, in the U.S. just six states have given their residents the right to die with assistance from a physician, and only if a patient has fewer than six months to live. One of those states requires a court order. Thirty-seven states have specific laws prohibiting euthanasia entirely.

Of course, a young mother has good reason to fight for her life, to do whatever it takes to gain time with her family. And that’s what Anna has been doing no matter how miserable the method. She managed to tack some time onto a life being cut tragically short. But in these final weeks she requires so much pain medication that sometimes she’s barely conscious. Still, she must know the people who love her—including both parents—are helplessly waiting for peace to come. She must be, too. Shouldn’t she have had the option to free herself, and them, from the pain before it came to this?

I don’t know that Anna would have chosen to hasten her end; as someone with a strong faith she might feel it isn’t, and shouldn’t be, up to her when the time is right. And perhaps as a mom, her desire to have one more day on earth with her young daughter, especially back when she was still able to interact with her fully, is more powerful than any other need.

Regardless, having that choice seems the right thing. Instead, the hand of the law weighs us down in our deathbeds, dictating this most personal of moments. Does all that fighting toward the end, often because a doctor hands you slim hope, prevent a good death? In many cases I think yes. Many of us might wish to say goodbye weeks or months before our dignity is gone and our pain is so severe it can’t be managed at home. Even at this late date I know I’d relish being able to say, at this time by these means. I’d find some small satisfaction in not letting the cancer have the final word.

We’ve long been taught that the ability to use our rational minds and make choices is a key to our humanity. And yet we continue to stand in our own way, debating the morality of employing that ability at the most sensitive of times. To me what’s immoral is not allowing choice, especially under such personal circumstances. My friend may be dying just as she should be, according to her beliefs. Maybe if I were in her place I would end up waiting it out, too. But her suffering through these last weeks has strengthened my resolve—to remain human, to keep choosing, until my final breath.

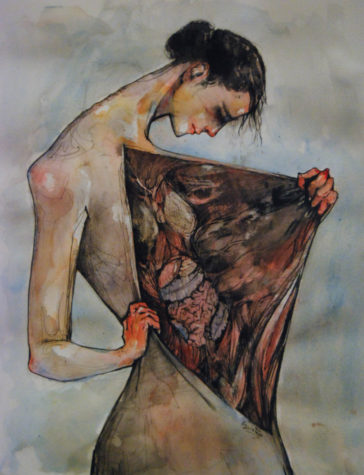

Image used with kind permission from the artist, Emily Quintero, for one-time use. See her work here.

A very moving piece and statement with which I am in total agreement.

Thank you!

This is an amazing story and statement! I agree with everything you say in every way.