I learned a lot of languages in my teens and 20s. I say “learned,” but don’t expect fluency. You shouldn’t try to have a very complicated conversation with me in any of them today. But there have been points in my life when I had dear friends with whom I only spoke Japanese or Norwegian. I can buy a watch in French and have occasionally exchanged very basic information in Spanish. Once I made a phone call in Italian—and the taxi showed up the next morning. At the right time!

But I’m not one of those people who can show up in a country, hang around in bars and youth hostels, and somehow magically “pick up” the language. All of these were pounded into my brain through large amounts of time spent in classrooms, going through flashcards, writing out sentences, memorizing dialogues, and so on.

All of that classroom-based learning meant that I often knew a lot, without really understanding how people really use these languages in the real world, and particularly how they avoid offending each other.

I was reminded of this the other day, when I listened to an episode of the delightful podcast The Allusionist about the differences in how English and American people use “please.” The main guest on the Allusionist was Lynne Murphy, an American linguist who lives in Britain and has studied the British and American usage of “please.” Yes, British people say it way more. No, it’s not because British people are more polite. We just use these words differently. You can read about some of her work in her blog posts about “please” and “please” in restaurants.

I used to live with a British man whose polite requests came off sounding like condescending demands–because of the “please.” (Eventually I realized this was a cultural difference and got over it.) By the simple act of moving to the U.S. and using English as he always had, was at risk of sounding condescending to the people close to him. And, I now realize, I sounded totally rude and obnoxious when I asked people for things in Britain using the normal American forms.

Oops. Sorry, everybody. It’s just how I talk.

So that’s me, offending people in my native language. How much worse must it be in all those other languages I’ve used over the years?

I think I did okay in Norway. Scandinavian languages, as was noted in the podcast, don’t really have a word for “please.” In Norwegian, you do have the option of asking someone to “be nice and” do something you want them to, but it’s not used very much.

Of course, it’s not just “please.” Another way to offend: using the wrong form of “you.” In English, we’ve only got the one now (since we dropped thee and thou), but many European languages have a formal “you” and an informal “you.” Norwegians aren’t big on formality, though. Norwegian has a formal “you,” but nobody uses it.

In German, though, I have made multiple people uncomfortable by using the formal “you” when I should have been informal. It was a combination of not really understanding where the borders between a formal relationship and an informal relationship are–plus a habit of lapsing back into the formal form, which feels safer. The last time I remember doing it, the person flinched, then corrected me. I felt terrible for being the blundering, awkward foreigner who doesn’t understand social context.

In Japan, there is no shortage of ways to say “please.” I can think of two main ones, each with several variations depending on who you’re talking to. Japanese has more forms of “you” than I’m going to try to count right now. Same for “I.” Verb endings change based on your relationship with the person you’re talking to. Even the verbs themselves can change. If I’m being particularly respectful of my interlocutor, I ditch “imasu,” the regular verb for saying “I am” and “you are,” and use “itashimasu” for myself and “gozaimasu” for the other person.

I found that having a set of strict rules on how to talk to people actually made it easier to be polite. Also, no one really expected me, a brown-haired, tall-nosed foreigner, to be able to use the more formal structures at all; I was granted a kind of pass to speak at a medium formality level that wouldn’t impress anyone, but also wouldn’t get me in trouble. The only time I can remember offending someone in Japan, we were speaking English. She wasn’t a native speaker and misunderstood a joke. I still feel bad about it. Oh, also, I once said something pretty dirty by mistake, and my friend just said “no! no! no! no!” a lot of times in a row. (Actually a Japanese word that means something like “don’t do that,” because you almost never say “no” in Japanese–it’s quite rude.)

Several of the comments on Murphy’s blog posts about “please” were complaints about how people should say please, and it’s more polite to do so. But politeness is in the ear of the beholder. The actual usage of language is so much more complicated than anyone’s imagined rules.

I love how learning foreign languages has given me windows into other cultures–while also giving me whole new realms in which to be confused, awkward, and rude. Sorry, world. I mean well.

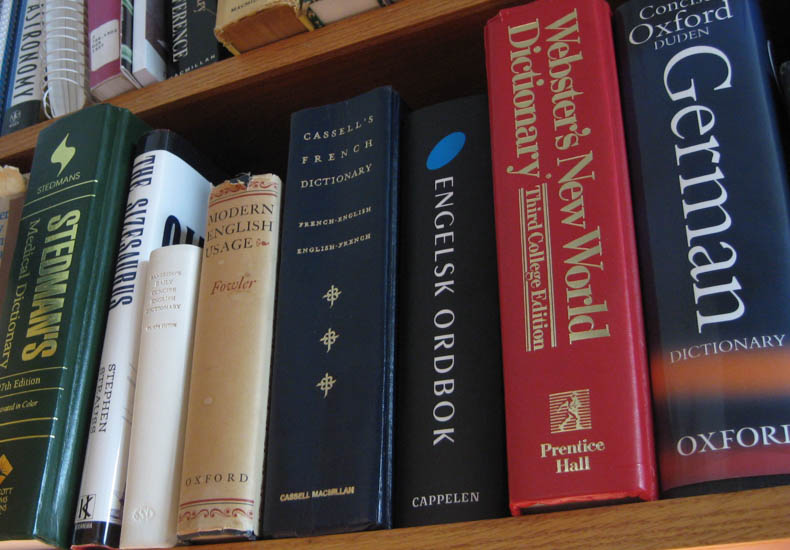

Photo: Helen Fields

I have the same problem with formal and informal “you’s” in Italian, and like thee, I opt for the formal: I’d rather be too polite than too presumptuous. So what exactly was the problem with being too polite, please?

I think, by using the formal “you,” I was creating distance in what was actually a closer relationship? That’s my best guess.

In Germany, I was invited to take part in a formal ceremony of ACQUIRED sisterhood which took place as a planned event at a restaurant. In a ritual manner, the two adults (I was one, the other was the grandmother of my infant Goddaughter) granted each other permission to refer one another as “Du”. We first each toasted each other saying our OWN first name. Then we linked arms with our filled wine glass in hand, took a drink, and nodded to one another. We NOW had formal permission to address one another informally, in a manner used only by very close friends – it’s like calling someone by their first name. I was amazed that the ceremony was so businesslike and structured. The wine was good. The company was, too.

Oh, my goodness, Leanne! What year was that? At the newspaper where I did a fellowship, they just told me something like “we use ‘du’ here” on the first day.

(Region may also matter. This was in Berlin.)

This “Du-tzen” ceremony was in 1973 with an elderly woman whose husband was a prominent medical professional. She was prim and proper, and very intelligent. I’m sure things have changed a lot since then. Anyone want to chime in here as to whether or not the Du/Sie chasm still exists to that degree?

To add another layer of complication to communication, social cues vary so widely. As an example that I have lived, for men in Japan it is more polite, and far less odd, to appear laconic in a formal situation where there is an inequality of status (or age) or the parties ‘haven’t been introduced’. Unfortunately, the average North American responds to silence with nervous volubility, appearing to the Japanese not a little unhinged.

The first time I met my father-in-law was long enough after living several years in Japan that I assessed the situation correctly: I wasn’t who he’d expected his daughter to be engaged to, and was going to be keeping her abroad, I had passable but far from fluent Japanese, I was in his home; I should shut up, keep his whisky glass full, and have as much or little conversation with him as he liked. We got on fine, or I should say he never led me to believe otherwise.