There is a blue velour–covered box in my house marked with the face of a pirate and the word “Plunder.” Like any piratical treasure trove, there are golden coins inside. There are also marbles, leftover buttons, and crow feathers. Sometimes, I’m not quite sure what makes some of the things inside the box so valuable. But there are a few small bits of colored glass in there that give me the itchy fingers a pirate might have had when discovering a map with a large X on it and a promise of doubloons.

There is a blue velour–covered box in my house marked with the face of a pirate and the word “Plunder.” Like any piratical treasure trove, there are golden coins inside. There are also marbles, leftover buttons, and crow feathers. Sometimes, I’m not quite sure what makes some of the things inside the box so valuable. But there are a few small bits of colored glass in there that give me the itchy fingers a pirate might have had when discovering a map with a large X on it and a promise of doubloons.

Sea glass comes from shards of glass—from bottles, from jars, from shipwrecks—that have been tumbled by waves, sanded by stone, and corroded by saltwater. Seeing a piece of glass on the shore feels like a kind of luck. Here’s something that the sea has worked so long to create (it may take 30 years or more). And it’s a journey completed: the glass in my hand was made with silica, the main ingredient of the sand to which it returned, in a different form.

Years ago, I found a book about sea glass that proved as irresistible to me as the treasures found on the beach. Pure Sea Glass: Discovering Nature’s Vanishing Gems by sea glass expert Richard LaMotte, covers everything from the different colors of sea glass to where to find it. Color is a way to date and source the glass that’s found. There’s soft blue from turn-of-the-century soda bottles and fruit jars; the extremely rare orange glass, from early 1900s orange tableware; black glass from before the mid-1800s; the Kelly-green, brown, and white that are tumbled shards from more vessels.

Those who want to find sea glass do research on areas that glass might have found its way to the sea, like historic waterfronts and shipping routes of years past. They might scour shorelines that the prevailing winds favor, and seek out the low tide following a storm with strong onshore winds.

Serious sea glass seekers, it seems, combine knowledge of the chemistry that creates the rainbow of glass hues with an understanding of the human and ocean conditions that create the treasures they seek. Sea glass itself has been used for at least one interesting study: estimating the maximum run-up of waves during extreme conditions.

But those who pace the beaches are finding there’s less glass than there used to be. The enthusiasm for sea glass is part of its decline, but the replacement of glass containers with plastic and aluminum ones, along with coastal cleanups and greater awareness of beach litter have whittled down the sources of sea glass. Restoration projects can also bring in sand without sea glass And glass seekers, too, are concerned that there will be even fewer treasures to find, and fewer beaches to find them on, as sea levels rise.

There’s enough plunder already in my house so that, for the most part, I leave the glass I see on the beach. I’m not sure why, but it always loses some of its seaside dazzle once I bring it home. (I’m sure a rare orange piece could change my mind.)

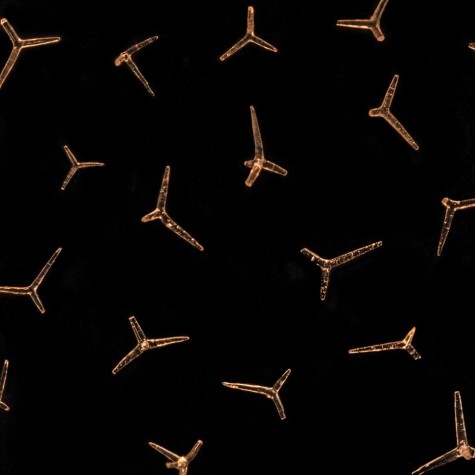

Besides, I’ve recently learned that there’s much more beauty on the shore. “Most people think of sand as boring, brown dusty stuff, maybe with glass in it. A bit of a nuisance that gets in your sandwiches on holiday,” explains UK-based Jenny Natusch in a delightful TEDx talk. She takes photographs of grains of sand sent to her from around the world, which appear intricate and delicate as snowflakes suspended under her microscope.

She calls herself a sandgazer. “So many people are stargazing…not realizing that there’s this wonderful, enormous, spectacular spectrum of life right under their noses. And if brown, dusty old sand is actually amazing, what else might we be missing?”

—

Top image by Akuppa John Wigham via Flickr/Creative Commons

This was a delight to read. Thank you! (Love the idea of your treasure trove….) 🙂