In the bespangled Pioneer Saloon in Paisley, Oregon, hangs a picture on a wall of a fit, gray mustached archaeologist out in the field. Written in pen, the name at the bottom of the photo is Dr. Poop.

In the bespangled Pioneer Saloon in Paisley, Oregon, hangs a picture on a wall of a fit, gray mustached archaeologist out in the field. Written in pen, the name at the bottom of the photo is Dr. Poop.

Dennis Jenkins is his actual name, a senior archaeologist at the University of Oregon. Jenkins leads paleo digs in the high sage desert around Paisley. They know him well at the bar.

Jenkins’ crews work a chain of caves standing over a sea of sage beneath the parapets of the Eastern Cascades. They have been finding layers of stone tools, megafauna bones, and, in particular, dried human feces dating back as far as 14,300 years ago. This is from deep in the Ice Age, remnants of the first people. It is the oldest human fecal artifact recorded in the Americas.

Thus, Dr. Poop.

Paisley Caves’ coprolites — there are many — are kept in tape-sealed containers in a lab adjoining Jenkin’s office on campus at the university. The plastic containers are clear and you can see the dusty clods inside, a bit of hair and digested plant, some darkness of meat. The sloughing of a Paleolithic person’s digestive tract left these little chubs packed with human proteins, a true sign of our species in North America.

“We’ve got horse hooves and sinew,” Jenkins told me as we went through the collection. “Camel bones with flesh still attached. Twelve-thousand six hundred years old, you can feel the flesh, you feel the fat on the bones.”

He squeezed the air just a touch.

“You’re sitting there looking at the bone saying this could be an animal hit on the freeway.”

I came to Jenkins because I wanted a sense of clarity for an era in which we no longer live. For me, it was a matter of remembering time beyond our brief generations. It is so easy to think that now is all that is happening. History can seem fabricated, as if it refers to legend rather than something that actually exists. The Wisconsin Ice Age and the first arrival of humans on this side of the planet is so far back in cultural memory it may not seem to be real.

In this case, it was poop that allowed me to see through in time.

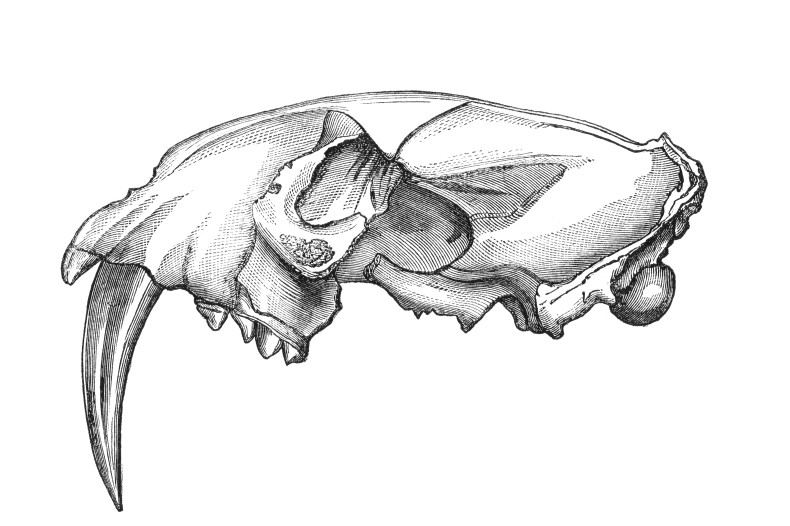

Most of the feces found in these dry caves came from wolves, coyotes, bears, and big Pleistocene cats.

“We got some American lion coprolites, which just stoked everyone,” said Jenkins. “They are in Pleistocene deposits, same age as humans.”

I asked how he knew for sure he had human coprolites and not the physical deposits of dire wolves or big cats that had eaten humans and shat them out.

Jenkins smiled. He’d wondered the same, if cats were eating people and depositing their digested remains into the cave.

“Either way,” he said, “it still means people were here.”

This is the question the poop answers: when were people in North America? It is at least a baseline. It should be noted, however, that many scientific claims have been lodged against these coprolites being human. Jenkins has gone to great lengths to prove otherwise. At the excavations, production has stopped at every piece of feces found, sometimes up to 20 times a day. Hazmat suits went on to prevent contamination of specimens, which were removed with tongs and tweezers for transportation. Jenkins maintains he’s found the real thing, the proteins of our species, as close as you can get to actual people.

Clearly 14,300 years ago puts a damper on the few archaeologists hanging onto the Clovis-first theory that people arrived 13,000 years ago. These human coprolites have become an archaeological lynchpin for the peopling of the continent.

Seeing human feces from the Ice Age in plastic containers is not enough, however. In order to adequately travel back in time, I had to see the place, too.

Paisley Caves are in a rough basalt outcrop bristling with greasewood and sage in the high desert of South-Central Oregon. Their grotesque entrances look like mouths of roaring trolls. These are not deep shelters, just enough overhang to get out of the wind. I camped here for a few nights, my tent set among black boulders and dry grass a quarter mile down the slope from the caves. I sat alone for hours with my dinner or a journal in hand looking toward the mountainous east end of the Cascades. I tried to imagine a lake that was once here, a glorious Ice Age sunset reflected right back at the sky by hundreds of square miles of glacial meltwater. What is left of that lake is now a vapid blue kidney called Summer Lake.

I couldn’t see Summer Lake from the foot of the caves. The Ice Age lakeshore had retreated eight miles. Had I been here 14,300 years ago, I would have been looking across marsh grasses and waterfowl.

A blustery wind whipped across the rolling sage plain, stirring dust from this dried Pleistocene lake bed. Cold rain squalls were coming in from the west. By night they would turn to snow.

I hadn’t gone into the caves yet, preferring to wait a day or two, enough time to get a sense of their surroundings, imagining the place in its Ice Age grandeur, the lake brimming, mountains laced in waterfalls and ice. But I started feeling silly sitting in the wind and rain at my camp when perfectly good shelters were ten minutes away.

I scrambled up to the church mouth of the nearest cave, a tall but narrow passage that ended a few feet inside. It had been a bubble in an ancient lava flow, one of the only decent places around here to get out of the wind.

This cave didn’t turn up human feces like some of its neighbors, but it did produce Pleistocene horse hooves and layers of camel remains mixed with muskox, wolf and coyote. The coyotes at the time were twice the size of those we know today.

As I squatted in the back out of the wind, I wondered if ghosts were still in this cave from that long ago. Or had so many winds scoured them out, leaving only this rind of stone?

I realize it’s not acceptable to believe in ghosts in fields of science, but you should know how many archaeologists actually do. They tell me, but they just don’t want it in print.

Some believe that echoes radiate from the past. Time and space are charged by what happened in a place. It could be no more than imagination, the mind filling in gaps between dry coprolites and the actual place where they were laid.

For me it is simple, scientific, observational. I need to see the poop firsthand, and then the place itself. This is a recipe for time travel. Piecing together science and landscape, I become aware of what happened long ago. I see people mingling with Pleistocene horses, mammoths, camels and enormous cats. The world becomes more than now.

Maybe this is what they call seeing ghosts.

Photo and images: Shutterstock

“The world becomes more than now.” This line is one of the most important concepts I’ve read and/or thought about in a very long time. This is a concept, which if adopted by mankind, could be just what we need to save our planet-in-peril. What a fascinating bit of ancient history.

Craig,

There was a article/paper quite a few years ago about a cast in the basalt of a pleistocene wooly rhino… I think it may be in that same general area you are writing about here. The author(Raynolds) is a geologist-extraodinaire in Denver at the Museum of Nature and Science. The cool part … you could climb into the cast/cave.