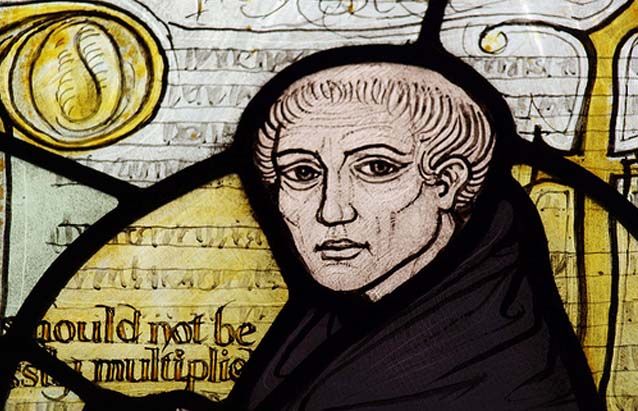

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about an old friend of mine named William of Occam. You know the guy I’m talking about, right? Skinny little kid in the monk’s robe who doesn’t say much. Sure you do. Some guys call him “Sharp Willy” or “Billy the Knife.” I’m not sure why, I assume it has something to do with the fact that he’s so skinny.

If you don’t know him, man, you’ve missed out. He’s quiet guy, keeps to himself unless he’s drunk. But once he gets going he’s hilarious. “Why say something if silence will accomplish the same thing?” he used to say to me. He was full of those kinds of quotes, which were awesome once you got him to stop saying them in Latin.

Anyway, in college Will and I would go drinking together and shoot pool every Thursday. I remember he was careful and fastidious – a real Type A, you know? He hated wasting anything. Time, words, pool cue chalk, all of it had to be just so. No more, no less.

Some guys thought he was either too haughty or too nerdy or just too quiet. But I liked him. He had a confidence that made you want him to think you were smart. Kinda like he was part of a club that wasn’t exclusive and didn’t lock its doors but that you were nevertheless intimidated to enter.

I remember this one time, we were playing pool and he was perfecting the amount of chalk on his cue – tapping, blowing on it, getting it just right – and I laughed and said, “Everything should be kept as simple as possible, but no simpler, right?” Then I leaned on my cue and casually said, “Einstein said that, you know?”

Will looked at the table and in one smooth motion leaned over it, lined up behind the cue ball and without breaking his focus on the three ball next to the side pocket, said, “No he didn’t.” Then, sliding the cue twice between his fingers he said, “The goal is for basic elements to be as simple as possible without surrendering a single datum of experience.” Blam! Three ball goes in. Then, still fixated on the table, “That’s what he said.”

Will looked at the table and in one smooth motion leaned over it, lined up behind the cue ball and without breaking his focus on the three ball next to the side pocket, said, “No he didn’t.” Then, sliding the cue twice between his fingers he said, “The goal is for basic elements to be as simple as possible without surrendering a single datum of experience.” Blam! Three ball goes in. Then, still fixated on the table, “That’s what he said.”

In anyone else, this might seem dickish, but Will pulled it off. He was just telling you stuff, not making you feel bad. And in point of fact, Einstein’s Constraint is actually longer and more complicated than this but Will had a habit of shortening everything to make it easier to understand. I liked that about him.

I hadn’t thought about that pool game in years until I went to China a few weeks ago to report one of the chapters of a book I’m working on. I was talking to traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) doctors, trying to understand how their form of medicine works and what it has to offer Western science-based medicine.

I was having a tough time because, while they certainly care deeply for their patients just like Western doctors do, TCM doctors have a bafflingly different sort of logic. In Chinese medicine, there is no formal experimentation, no standardized rules, no way of measuring one treatment against another. Everything works and anything can work, just so long as it actually works. Even when it doesn’t work that doesn’t mean it doesn’t work.

One practitioner told me that if one person goes to four doctors and all of them give him a different diagnosis and a different prescription, it’s totally possible that they can all be right. “Different paths to the same destination,” she said, wisely.

She also said that mercury, in some select cases, can be used as medicine and that rhinoceros horn is good for getting fevers down. It’s not my job to argue with the people who have taken time out of their day to talk to me but I couldn’t help it. If all things work and all diagnoses are equal, then there’s an infinite number of treatments for a disease. Nothing’s true or certain, it’s all just a big mess.

“Isn’t it simpler to just assume that the healing is happening in the patient’s head and not because of the treatment?” I asked.

“Interesting question,” was the response. “No, it’s not.”

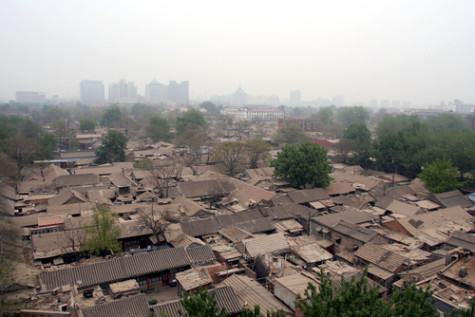

I was confused and frustrated later that night, sitting alone in a tiny Beijing hotel room with a view of brand new skyscrapers in one direction and dilapidated slums in the other. I was lonely and bored and all of a sudden I thought of my old buddy Will. I pulled up my contacts and searched for his number. There it was. It seemed he had a job now as a sub-editor at the journal Nature. He must love that – cutting and trimming other people’s work, taking out every unneeded word. I wondered which of my stories he might have cut to ribbons, smirking as he went.

I was confused and frustrated later that night, sitting alone in a tiny Beijing hotel room with a view of brand new skyscrapers in one direction and dilapidated slums in the other. I was lonely and bored and all of a sudden I thought of my old buddy Will. I pulled up my contacts and searched for his number. There it was. It seemed he had a job now as a sub-editor at the journal Nature. He must love that – cutting and trimming other people’s work, taking out every unneeded word. I wondered which of my stories he might have cut to ribbons, smirking as he went.

“Hi, Erik,” he said after one ring, as if we had only spoken last week and not 16 years ago. “What’s up?”

“Hey man, good to hear your voice,” I said and proceeded to tell him all about my troubles, about the infinite, circular logic of traditional medicine and how there had to be a simple answer to it all.

“Listen man,” he said and I could tell by his tone he didn’t have a lot of time to talk, “you are thinking about this too much like a Westerner. Who’s to say that the shortest path has to be the best one?”

“But Will,” I said, “You are the one who always said, and I quote, ‘All things being equal, the simplest explanation tends to be the right one.’”

“No I didn’t,” he said, shortly.

“Yes,” I said, “you did. I remember it distinctly.”

“No,” he said, “Jodi Foster did. In Contact. You loved that movie.”

“Oh right. God, I could’ve sworn that was you.”

“You’re not the first person to say that. But no, I’m the one who said, ‘Only faith gives us access to theological truths. The ways of God are not open to reason.’”

I hung up the phone, more confused than when I picked it up. I had forgotten that before everything else, Will was a religious guy. That was one of the many reasons we never met a lot of girls when we hung out. That, and he was a little abrasive.

It occurred to me that for many people, faith in science is the same as faith in God or faith in traditional healing. It’s only the few people who perform the experiments who don’t need faith because they have evidence. For the rest of us, we have to have faith in the process. Faith that the person holding the test tube is telling the truth. At the very least, faith that our doctor knows her job.

And I realized that sitting in a doctor’s office, frightened for your life, the decision between the simplest answer and the one that best puts your mind at ease is easy. Whatever works – whether it works or not.

It was getting late and I was jetlagged. So I put the phone back on the stand, took a melatonin pill to help me sleep and put out the lights.

Photo Credit: Shutterstock

I love this, Erik. But I thought Occam’s Razor also laid out the principle of parsimony and Wikipedia, which says other people (Einstein, Newton, etc.) did too, quotes him: “It is futile to do with more things that which can be done with fewer.” So he said both, right? parsimony and faith/reason? It’s entirely possible I’m not thinking clearly. I often think not-clearly.

Oddly enough, Will doesn’t really like talking about parsimony all that much. He claims it was all taken out of context. He says he was searching for spiritual truth and not really the worldly kind. He I think he’s just being overly humble – he does that. He also says John Punch is “a douchebag,” which I think is a little harsh.

The idea of William of Occam as a sub at nature is so inspired I can’t handle it.