Recently, in the sumptuously warm waters off Maui, a woman went out snorkeling, got separated from her two friends, and was killed by a shark. Her body was found floating facedown about 200 yards offshore; the wounds on her torso told of her tragic end.

Recently, in the sumptuously warm waters off Maui, a woman went out snorkeling, got separated from her two friends, and was killed by a shark. Her body was found floating facedown about 200 yards offshore; the wounds on her torso told of her tragic end.

Considering how many of us spend time in the world’s oceans, unprovoked shark bites are pretty rare (fewer than 100 worldwide annually, according to the International Shark Attack File), and deaths by shark are even rarer. Writing about these animals some years back for National Geographic, I read that more people die under a toppled vending machine than in a shark’s mouth. (People get really mad when their Doritos get stuck.) While I’m not 100 percent confident in that statistic, it makes my point.

Still, sharks do bite people and, at least every since Jaws first aired in 1975, there is a deep, dark fear that seems to ripple through the populace of dying a violent and lonely death in the jaws of one of Earth’s most powerful predators.

Part of that fear, I think, is of the sea itself. I wonder: If you surveyed people asking the rather ridiculous question “Would you rather be attacked by a bear in a forest or a shark in the ocean,” would most would prefer the former? Think about it: A shark is basically a bear plus deep water and no air. The mauling would of course be horrific either way. But not drowning in a huge body of dark water, to some, might makes a land-based death seem somehow less terrifying, even though in truth drowning might mean a quicker end. But there’s something about a vast ocean, in this context, anyway, that suggests being bone cold and utterly alone.

Still. I love the sea. I love being in the sea. And there’s probably nothing more thrilling to me than wandering around that living art museum, especially when there are big creatures about. Getting close to marine life makes me extremely happy. I rarely think about what might sting or attack me or that drowning is a possibility. I’m far too excited that I just glimpsed an octopus, that there’s a massive green eel poking its head out of the coral, that a grouper as big as a small car (think Fiat 500) is following me around like a lonely dog. I feel honored to be among them.

And then there are sharks. I’ve met quite a few of them. Nurse sharks and lemon sharks are good for beginners—you can be nice and close and they show little interest and no aggression. Reef sharks can get a bit feisty if they’re trying to eat and you’re in the way, but for the most part, in my experience, they’re also pretty benign if you leave them be. I’ve gone eye to eye with an oceanic white tip, but only from a cage. Not one you want to mess with. Whale shark? Still on my dream list. Great whites? Haven’t met one and, unless I were behind bars, I might poop in my wetsuit if I did. Sorry, but I’m just being honest. That’s the one shark whose face makes even me—lover of all creatures great and small—shiver. (That doesn’t mean I want them dead. I just don’t want one to surprise me.)

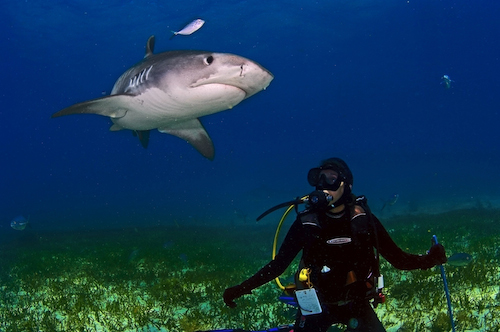

And then there are the tigers. Huge. Stunning. Reputed to be the “garbage disposals of the sea” meaning always hungry and undiscerning when it comes to food. One would expect, terrifying. But that’s not how I experienced them.

In the Bahamas there’s a spot about 60 feet down, at the edge of a straight-down drop-off into deep water, that some call Tiger Beach. Tiger sharks—big females, for the most part—tend to hang out there. It’s like some kind of spa for these girls, with its warm water, darts of sun hitting the sand, and good food.

Now, most people who go on a shark dive do so through some dive outfit with a bunch of other people, a buddy system, and a long list of rules with no exceptions. Which makes sense—these are dangerous animals and dive companies don’t want to lose their customers. It’s bad for business. (And ultimately for sharks.)

But one benefit of being a science writer is that sometimes you get to do stuff in a less formal way than is usually allowed. I was with a photographer and his assistant, plus our shark-conservationist guide—who discovered this shark-rich spot—and a shark biologist. We made a great team, and we all understood that the more interaction with the sharks, the better for the story. I’ll admit, when it comes to being near wild animals, going one step beyond absolutely safe is okay with me. The rewards, for the article, but mostly for me personally, are worth it.

And that means on that trip I spent many hours (not all at once) kneeling on the sandy bottom with nothing more than an arm-length white PVC stick to discourage any overly curious animals. Mostly, that stick was jabbed in the sand to keep me steady. Others from the team were nearby, and we’d been well briefed on safety. But it was lovely not having a big group of twitchy divers milling around and kicking up sand; I could feel it was just the animals and me.

The sharks, who became “the girls” in my mind, circled me at varying distances, swimming evenly and calmly. I pivoted with them, making sure I knew where each one was, admiring their imposing size and the subtle tiger-stripe markings along those smooth, gray bodies. I felt like I was the center weight of the sea-creature mobile I had over my bed as a kid. And it was just as calming—here, my breathing and a few undersea clicks and clacks the only sounds—yet exhilarating at the same time. Visibility was pretty good, but more distant sharks would disappear, then reappear as they moved in from the circle’s murky edges. It was surreal.

I felt no fear. Which might have been naïve. Even dumb. But my instinct with animals has always been solid. So I went with it, trusting that if I stayed calm, so would they.

And then one shark’s swim circle became a bit tighter. And tighter still. She was soon passing close enough that I could reach her with the poker, if need be.

And then one shark’s swim circle became a bit tighter. And tighter still. She was soon passing close enough that I could reach her with the poker, if need be.

But I had a better idea, one that would break one of the few rules we’d been given. It’s a moment I’m not totally proud of, one I don’t mention when I talk to kids about my work. (Mostly, I’m a good role model.)

I took off one of my dive gloves and waited. If she stuck to her pattern, the shark’s next move would take her exhilaratingly close. She turned and cut in toward me, as I expected, and I stayed still and kept my eye on hers as she closed in. Practically on me now, she swiveled slightly, just enough. She was a massive cylinder of steel, gliding past, less than a foot from my face.

Then, I reached out my hand.

———————-

Images:

Top: The Swirl, shot by “gaftels,” taken from Flickr Commons

Licensing agreement: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/legalcode

Bottom: J. Holland with tiger shark, Bahamas, shot by Brian Skerry, on assignment for National Geographic

.

Considering some of the descriptions of bear victims that I’ve read, I’d rather get attacked by a shark. It sounds like with sharks, either you die quickly, or you survive with a piece of you more or less cleanly removed. As opposed to bears that will do a Bolton on you (sorry, Game of Thrones reference for those who didn’t get it).

Got it. Yeah, probably true. But the water thing does seem to scare a lot of people. Fortunately, this isn’t a choice most of us have to make. (: