You may have read last week that you should start wearing sunscreen at night. This was bad news for me: I’m already a hopeless victim of sunscreen marketing, slathering the stuff in rain or shine, in London fog, at dusk. I just can’t stop, despite mounting evidence that regular sunscreen may be less protective than advertised, and may even help cultivate a Vitamin D deficiency. And then, last week, Yale researchers found that UV rays keep wrecking skin cells up to three hours after the last photon has hit the skin. This implies that in addition to the SPF 45 I use during the day, I should stock my night table with an “ex post facto” overnight sunblock. With ingredients like vitamin E and antioxidants, this hypothetical cream would act like the Plan B of sun protection, undoing damage after it had ostensibly already been done.

While “night-time sunscreen” was an arresting image, though, that product (which is probably more like an aftersun) wouldn’t solve the fundamental problem: how do I get enough sun to be healthy without getting enough sun to give me cancer? What I really want is something that amps up my skin’s natural sun defenses 24-7 from the inside out. Many different ideas are knocking around various labs, and some might be on the market soon. The best ones manipulate melanin, so in addition to letting me ditch the goopy creams, they’d give me the Mediterranean glow I’ve always been so careful to avoid.

Melanin is the pigment in your skin that determines whether your natural coloring is transparent, inky, or anything in between. The more of it you have, the darker you are, and the better your skin is protected from sun damage (in the US a white person has a 1 in 50 chance of developing melanoma; for a black person the risk drops to 1 in 1000). Why? Melanin snatches up the energy from UV radiation, preventing it from wreaking havoc elsewhere in the skin.

Unfortunately the story doesn’t end there. Doug Brash and his colleagues at Yale found that even several hours after the melanin-producing cells, called melanocytes, absorb the photons’ energy, they continue to produce molecules that damage the skin’s DNA. Call it melanin’s dark side.

By itself, an aftersun treatment that could mitigate this effect wouldn’t be enough. “UV irradiation is dangerous by multiple mechanisms,” says David Fisher, chair of dermatology at Massachussetts General Hospital. The mechanism Brash found, he says, is a new and significant addition to a long list, including the direct effects of UV light on DNA. Intriguingly, though, UV isn’t the only problem. Some kinds of melanin don’t need any help from the sun to be dangerous.

People with very fair skin are at higher risk for melanoma not simply because of the amount of melanin in their skin but because of the type. There are two kinds of melanin — pale-skinned redheads have pheomelanin; people with dark skin or hair have a dark brown or black variant known as eumelanin.

In the early 2000s Fisher was studying fair-skinned, “red-haired” mice to better understand the tanning process. He discovered that these mice’s melanin variant, pheomelanin, didn’t just inadequately protect against UV rays — something about the pigment itself encouraged their skin to develop melanoma.

This is down to something Fisher discovered about the general mechanism of the tanning process. UV rays don’t directly trigger the production of melanin. Instead, it’s a chain of events that starts with the photon hitting the skin and ends with a change in the melanocytes. In redheads that chain is faulty, which explains their greater cancer risk. Might it be possible to tweak this pathway? Instead of triggering the tanning process with a photon, could you use a topical drug to convince the skin to kick-start its own melanin production? Then there would be no stray energy for the melanocytes to pass on to other parts of the skin. You’d have a healthy tan that mimicked naturally high melanin levels and thereby lowered the risk of skin cancer.

Fisher devised a lotion that did exactly that — it tanned the pale mice and drastically cut their skin cancer risk. This was no Jersey Shore paint job; his drug worked at the cellular level, from the inside out to make the skin natively more resistant to sun damage.

Of course, the course of true love and science never did run smooth — they’re still working out how to apply their successes on mouse skin to much thicker human skin. “We have finally found several compounds which do [topical skin darkening] in normal human skin,” Fisher told me. He and his colleagues have been testing the drug on discarded human skin.

Fisher isn’t the only one working on sunless tanning: Scenesse, an Australian drug under review by the US Food and Drug Administration, works on the same general principle to boost melanin production for a protective tan. King’s College London researchers are studying natural sunscreen compounds used by coral-dwelling algae to protect themselves against the harsh all-day sun that shines through clear water. There’s even a pill packed with anti-oxidants to undo some of the sun’s energetic damage (though it won’t confer that glowy tan).

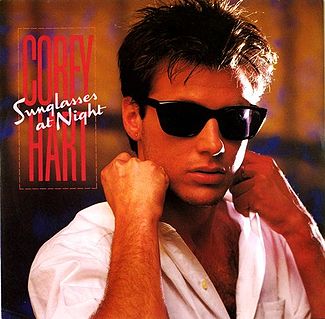

Until these hit the market, if you’re like me and worry endlessly about balancing your Vitamin D with your UV exposure, you can check the UV forecast. Or you could get one of these nifty little wristbands. I’ll probably keep applying sunscreen with irrational zeal. And don’t get me started on eye protection.

Photo credits:

Sunset: shutterstock

Sun- and moon-screen: shutterstock

Corey Hart’s album cover: fair use

what about methoxsalen? I recall the early 60’s book Black like me where methoxsalen was used to darken the authors skin?