In early February this year, a few days after a magnetic resonance image confirmed that an aneurysm at the root of my aorta had reached a worrisome size, I received a phone call from the office of my primary care physician. The MRI had picked up an “incidental” finding, unrelated to the aneurysm; could I come into the office to discuss it?

In early February this year, a few days after a magnetic resonance image confirmed that an aneurysm at the root of my aorta had reached a worrisome size, I received a phone call from the office of my primary care physician. The MRI had picked up an “incidental” finding, unrelated to the aneurysm; could I come into the office to discuss it?

The incidental finding turned out to be a type of pancreatic cyst called, ominously, an intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN). It’s probably nothing to worry about, my doctor assured me, but it would be prudent to have a high-resolution MRI of the abdomen and the pancreas to get a better look at what we’re dealing with. The MRI confirmed that the cyst was an IPMN, about 2 centimeters (almost an inch) long. The recommendation: repeat the MRI in 3 months to make sure nothing has changed.

At that point, I was in full reporter mode, having just learned that my aortic aneurysm, which I had basically dismissed for 12 years, could no longer be ignored. I set out to learn all I could about IPMNs. It’s an interesting story that raises hopes of early detection of more cases of pancreatic cancer—one of the deadliest cancers—and some tricky questions about the benefits and costs of screening for these and similar lesions. It would be an even better story for me if I were not in the middle of it.

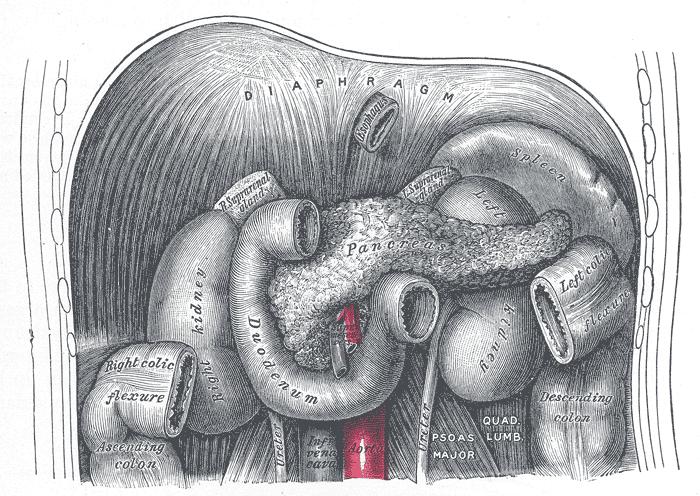

IPMNs are mucous-filled cysts that grow in ducts that thread through the pancreas and carry gastric juices to the intestines. When they are small they generally cause no symptoms. But they are increasingly showing up as incidental findings on MRI or CT scans, as imaging has become more widely used and the resolution has improved. A study at Johns Hopkins found that IPMNs were detected in 2.6% of patients who had no known pancreatic problems but underwent CT scans for other reasons. And the incidence increases with age—IPMNs showed up in CT scans of 8.7% of those in their 80s, the Hopkins team reported.

IPMNs are mucous-filled cysts that grow in ducts that thread through the pancreas and carry gastric juices to the intestines. When they are small they generally cause no symptoms. But they are increasingly showing up as incidental findings on MRI or CT scans, as imaging has become more widely used and the resolution has improved. A study at Johns Hopkins found that IPMNs were detected in 2.6% of patients who had no known pancreatic problems but underwent CT scans for other reasons. And the incidence increases with age—IPMNs showed up in CT scans of 8.7% of those in their 80s, the Hopkins team reported.

IPMNs have a significant potential to become cancerous, but there are no good tests to determine precisely which ones will progress. One thing is clear, however: location matters. IPMNs in the main duct, which runs the length of the pancreas, have a 50% – 70% chance of becoming malignant, while those in the numerous branch ducts that feed into the main duct have a much smaller chance of doing so—generally less than 20%, and in some cases the likelihood may be considerably less (yes, the numbers are squishy). I got lucky: mine is in a branch duct.

In lieu of a test to predict which IPMNs will become malignant, physicians use an array of clinical features to identify the most worrisome ones. In addition to location (main duct or branch duct), they include the size of the cyst, whether it contains any solid material, the thickness and appearance of the wall of the cyst, changes in its size or appearance over time, and whether the patient has any symptoms. These were laid out in international consensus guidelines published in 2012.

For the most worrisome cysts, the recommendation is surgical removal. Why not remove any that show up? The main reason is that it’s not simply a question of cutting out a small tumor. In most cases the surgery, which is called the Whipple procedure, involves excising a large chunk of the pancreas along with the duodenum, and reconnecting the bile duct and the small intestine. It’s not an operation to be undertaken lightly. But in cases where cancerous cells in an IPMN have not invaded surrounding tissue, surgery is highly successful in removing the cancer threat.

Given all the complexities and unknowns, I figured I needed some expert advice. Again, Johns Hopkins seemed a good bet. It has a multidisciplinary clinic devoted entirely to pancreatic cysts, with a team of physicians, surgeons, radiologists, and researchers, including one of the world’s leading cancer researchers, Bert Vogelstein. I made an appointment for mid-May.

The team reviewed the MRI I had in February and recommended that during my visit to Hopkins I should have a high-resolution CT scan of the abdomen and an endoscopic ultrasound—a procedure that involves passing an ultrasound device at the end of a thin tube through the esophagus and stomach into the small intestine, where it sits right next to the pancreas. The device takes clear pictures of the pancreas and can also be used to steer a needle into a cyst to remove cells.

The tests were reassuring. The clinic’s director, Dr. Anne Marie Lennon, a lively Irish scientist-physician who performed the ultrasound procedure, explained that the cyst had no particularly worrisome features. In fact, she decided it wasn’t worth running the small risk of extracting cells from the cyst. One surprise, to me, was that the images indicated two more small cysts in other parts of the pancreas. But it wasn’t a surprise to Dr. Lennon: 25% to 40% (again, the numbers are squishy) of patients with branch duct cysts have two or more of them.

The team’s recommendation was to do an MRI in 3 months to check for any changes. That occurred in August: no changes. So I’m now on a 6-month monitoring schedule. Because so little is known about the natural history of branch duct IPMNs, I’m likely to be monitored for the rest of my life. I’ve also signed up to be part of a research study; it seemed the least I could do to help in the understanding of IPMNs.

I consider myself fortunate that I learned of two completely asymptomatic but potentially killer lesions before it was too late. Wouldn’t it be prudent to broaden screening for these lesions so more people would catch them in time? That gets into some controversial territory.

For the past few years, debate has been raging over whether women under 50 should have routine mammograms and whether smokers should be screened for early signs of lung cancer using an X-ray procedure called a spiral CT scan. In each case, there’s a strong argument that the costs of such screening—including the large number of false positives that are likely to turn up and the personal anguish and cost of following them up—outweigh the benefits. But an outcry from patient groups and radiologists has tipped the public debate toward screening.

For relatively low-incidence conditions such as pancreatic cysts and aortic aneurysms, the costs of general screening would almost certainly outweigh the benefits. In terms of public health, reducing smoking—a risk factor for both conditions—would have a much greater impact.

But as medical imaging becomes even more widespread, incidental findings will become increasingly common. That will also be a mixed blessing. Many incidental findings will require additional tests and expensive follow-up, yet will turn out to have little medical significance. Others, in lucky patients like me, will offer a chance of intervention before it’s too late. Of course, luck is relative. I’d be even luckier if that incidental cyst were not there.

This is the sixth in a series. The final part comes in a week, on Monday, 11/17: $64,000 Questions

§

__________

Colin Norman has been a science journalist for more than 40 years. He is the former news editor for Science magazine and currently lives in Lewes, Delaware.

________

Photos: pancreas in context – via Wikimedia Commons; Henry Seymour Kaplan (1918-1984) with Maureen Lyles D’Ambrogio – Stanford Medical History Center

Dear Colin,

Thanks for sharing your experience. Reading it, I thought you should probably know about a new technology called Confocal Laser Endomicroscopy (CLE) that is now proven to be a useful addition to the armamentarium of the gastroenterologist, especially for pancreatic cyst characterization. The needle-based version of CLE is used for imaging the inside wall of a pancreatic cyst during an EUSFNA procedure, with the purpose to provide microscopic images of the cyst, which in turn can help the attending physician characterize the cyst. Several publications in the best peer-reviewed journals have shown that physicians using nCLE can now characterize IPMNs and – even more importantly – Serous Cystadenomas (fully benign cysts) with 100% specificity. While Dr Lennon does not have the technology, I believe she knows about it. I would be happy to point to key recent publications that might be of strong interest.

Very best wishes.