A local restaurant reviewer has a monthly feature in which he lists openings and closings of eateries around town. The list only contains the restaurants’ names and addresses, which always seems especially stark when it comes to the places that have shut their doors.

A local restaurant reviewer has a monthly feature in which he lists openings and closings of eateries around town. The list only contains the restaurants’ names and addresses, which always seems especially stark when it comes to the places that have shut their doors.

It’s the culinary equivalent of a gravestone. There’s nothing about the buckwheat crepe with fava beans and goat cheese, or the martini with habanero-infused vodka, or the truffle-stuffed chicken—or the people you remember sharing these things with you.

After they sell off the giant pots and the Hobart mixers and the light fixtures, maybe the most important things a restaurant leaves behind are memories. But sometimes, there’s another record, too: menus. And these days, menus are being used to create not just a history of how we live and eat, but of how the world around us is faring as well.

At the New York Public Library, more than 45,000 menus display dishes of ages past as part of the library’s rare books collection. These menus started to accumulate at the library around the turn of the previous century, where an enthusiastic library volunteer, Miss Frank E. Buttolph, began collecting what would eventually be 25,000 or more menus she found during more than two decades.

These days, chefs come to the menu collection to be inspired; novelists visit it to give their characters period-appropriate meals. Food historians have studied the menus to learn more about what the 1% of the past considered fine fare (one favorite: macaroni). Volunteers are working on digitizing them so the menus’ choice morsels can be more easily perused.

A little over a decade ago, an oceanographer from Texas A&M came in to look for fish. He went through 400 boxes of menus that show the interplay of diners’ changing tastes and the effect on fish stocks, with Atlantic halibut giving way to cod, halibut, then scrod as species toppled like dominoes. East Coast oysters, on the other hand, remained a steady menu treat—and all the menu information gathered became part of a global census of marine life.

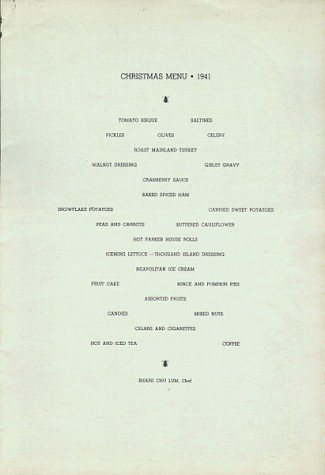

More recently, the Pacific Ocean has gotten the menu treatment, too. In the waters surrounding Hawaii, the lack of regular fishing records until 1948 has made it difficult for researchers to learn more about historic populations of fish and other marine species. Sea turtles are one of the creatures that Kyle Van Houtan, a NOAA marine ecologist in Honolulu, has been interested in learning more about. Honu were legally hunted in Hawaii until the 1970s, when both state law and the Endangered Species Act banned the practice. (This protection doesn’t extend everywhere. “Now, when we think of turtles, we think of ‘Finding Nemo’ and tattoos,” Van Houtan says. “But it’s also food today for many people around the world.”)

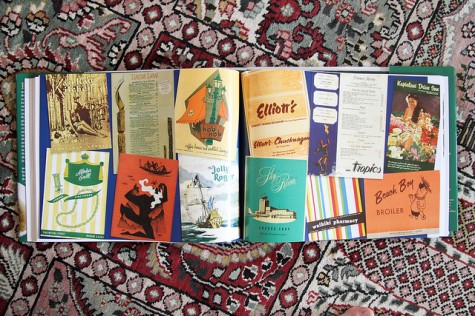

There had been speculation that fisheries—perhaps catering to visitors that started to throng the islands–drove the Hawaiian turtles’ decline. So Van Houtan approached private menu collectors, first finding a local publisher who had collected 30 menus from around the time of Hawaiian statehood. Then he found more menus at libraries and through other collectors.

These days, a trip to Hawaii may seem like tame adventure for some. But back then, people considered visiting the islands the trip of a lifetime. Travelers would hang onto menus as a souvenir of their island vacations; some employees, too, kept the menus as mementos of their days as bussers or bartenders. Of the 500 menus Van Houtan studied from between 1925 and 1975, only nine listed turtle as an offering. Their decline, he says, is linked to something other than restaurant demand.

These days, a trip to Hawaii may seem like tame adventure for some. But back then, people considered visiting the islands the trip of a lifetime. Travelers would hang onto menus as a souvenir of their island vacations; some employees, too, kept the menus as mementos of their days as bussers or bartenders. Of the 500 menus Van Houtan studied from between 1925 and 1975, only nine listed turtle as an offering. Their decline, he says, is linked to something other than restaurant demand.

And his menu research has only begun. In a study last summer in Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, he and colleagues found that menus can reveal what’s happening in the water. Now, they’re combining menu data with fishery logbooks kept since 1948, along with surveys of the Honolulu fish market from 1902 and 1903 to explore trends in both coastal and oceanic fishing grounds. Among other things, they’re seeing that the fisheries start to move offshore as time passes, Van Houtan says, and shift to a higher trophic level, favoring large, predatory species like sharks and tuna. There are trends over time close to shore, too, with early fisheries bringing in a wider array of species, particularly focused on the lower strands of the food web.

Today, few people seem to keep paper souvenirs of the sort that Van Houtan’s using. But someday, Instagram food shots and Chowhound reviews might serve a new purpose, too. Maybe years from now, researchers will pore over these food memories we’ve made, searching for clues about how the world turned into the place that it will be.

**

Images from Flickr: Wally Gobetz; Navy Medicine; Robyn Lee.