A while ago I was on a panel for the local science writing association, and each panel member was assigned to talk about writing about science in a way that’s both literary and beautiful. I gave my talk and a few days later, it was posted on the association’s website. Much social media ensued, all of it kind and generous. But I’ve been uneasy about that talk: it digressed, its logic slid around. So I’d like to rewrite it here; that is, I’d like to write the talk I should have given. Also I couldn’t think of what else to post today. And besides, I’ve kept the nice bits.

A while ago I was on a panel for the local science writing association, and each panel member was assigned to talk about writing about science in a way that’s both literary and beautiful. I gave my talk and a few days later, it was posted on the association’s website. Much social media ensued, all of it kind and generous. But I’ve been uneasy about that talk: it digressed, its logic slid around. So I’d like to rewrite it here; that is, I’d like to write the talk I should have given. Also I couldn’t think of what else to post today. And besides, I’ve kept the nice bits.

So, the assignment: science writing that’s literary and beautiful. “Beautiful writing” is a phrase I use a lot – “what a beautiful writer,” I say. I dislike the phrase, “literary beauty,” because it’s pompous and probably undefinable but I’ll use it anyway.

Literary beauty usually refers to fiction; it means writing the way fiction writers write. I love reading fiction; I read much more of it than nonfiction and often because it’s better written. I think the reason for this is that nonfiction writers – and Lord knows, science writers – have enough to do just understanding the subject and its context and writing it clearly and accurately and accessibly, without worrying about writing it beautifully.

Literary beauty usually refers to fiction; it means writing the way fiction writers write. I love reading fiction; I read much more of it than nonfiction and often because it’s better written. I think the reason for this is that nonfiction writers – and Lord knows, science writers – have enough to do just understanding the subject and its context and writing it clearly and accurately and accessibly, without worrying about writing it beautifully.

Nevertheless, ambitious and painstaking nonfiction writers do use the techniques of fiction. They call this literary nonfiction and for a while I thought it was interesting. I was an English major and before I’d even heard of the Big Bang, I was learning about the devices of fiction: about narrative arc and rising action and climax; about establishing character through foils; about using landscape to set mood; about finding the right detail to establish setting; and creating dialog that convinces the reader and reveals the character; and creating the voice of the narrator; and controlling the rhythms of sentences and the sounds of words; and so on and on, including never once ever using even one cliché – which only tells the reader that the writer doesn’t care enough about whatever it is to say it right.

In retrospect, I don’t think learning all that has been particularly useful, especially when the story is about science. Granted, the narrative arc stuff is useful for all science stories; so is the rhythms and sounds stuff. And granted, the rest of it is useful for writing about the scientists themselves because somehow the scientists have to be evoked. The reader has to see the scientists, as though the scientist is right there in the same room. The writer has to treat the scientists as characters: choose the right details to describe the characters, let the characters talk an awful lot, watch what they do, place them in their settings.

But that’s as far as I’ll go with literary nonfiction because fundamentally I don’t trust the premise. Isn’t the point of nonfiction, and science writing in particular, that the readers enlarge their understanding of the world? And that to do that, they have to trust the writer, and that means the writer has to tell the truth. The writer can’t go haring off, creating mood by pretending that the Space Telescope Science Institute is dark and brooding, or creating foils by rigging scientists’ characters so that one is cheery and the other one anxious.

Fiction is art, a collection of made-up facts and impressions in a made-up world that uncannily evokes in a reader the same world. Fiction can feel true and entirely believable – you can read a novel and after it believe that no marriage is ideal, we should just quietly adjust to each other, until you read the next novel which makes it clear that marriage is a bad bargain and you just throw the bastard out. Readers expect fiction’s truths to be like this, believable but idiosyncratic and partial and temporary; and readers don’t mind because they’re in it for the evocation, the experience of someone else’s world.

Nonfiction arranges facts into a story, it finds the story in the facts. Readers are not in for evocation of someone else’s world. They’re in it for the truth about the world we all must share, for understanding those facts. Without facts, nonfiction is unreliable and readers’ understanding of the world is correspondingly untrustworthy. Untrustworthy authors/narrators in fiction are charming; in nonfiction, they’re a waste of time, they’re worse than useless, they’re a betrayal.

Here’s a story. Years ago, I was running a workshop class for young science writers. One of them, a medical writer, sent around a story to be discussed by her classmates, who liked the story. The first paragraph was an anecdote about some parents whose son had some terrible disease, talking out their grief and fear. The class liked the anecdote, they cared about the parents. “No, but the anecdote was made up,” said the young writer. She had an appointment to talk to the parents but she hadn’t done it yet so she made up the anecdote as a placemarker. The class was really pissed. They were so pissed I was surprised. I thought she had a good reason for making up the anecdote, and she wasn’t really lying to them. Then I thought, her reasons and intentions are irrelevant. What’s relevant is that her classmates believed her and what she said wasn’t the truth. They believed a thing that was untrue and that she knew to be untrue. She looked them in the eyes and lied. They wanted her taken out back and shot.

So as science writers, we should go ahead and treat our scientists as characters and their discoveries as plots; and find pretty analogies; and control rhythms; and look for the central conflicts; and write with our own peculiar voices. But our readers have a different covenant with us. They trust us, they think we’ll tell them the truth. They think they can put that truth into their worlds and rely on it. And if they believe us and we betray them, they’ll be pissed.

And if we still want literary beauty in science writing? We have no option but to find the beauty in the facts, in reality, in our mutual world. And write about that.

__________

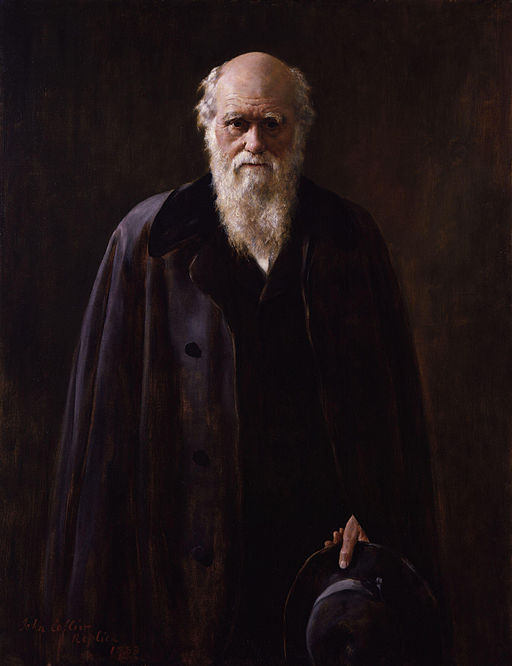

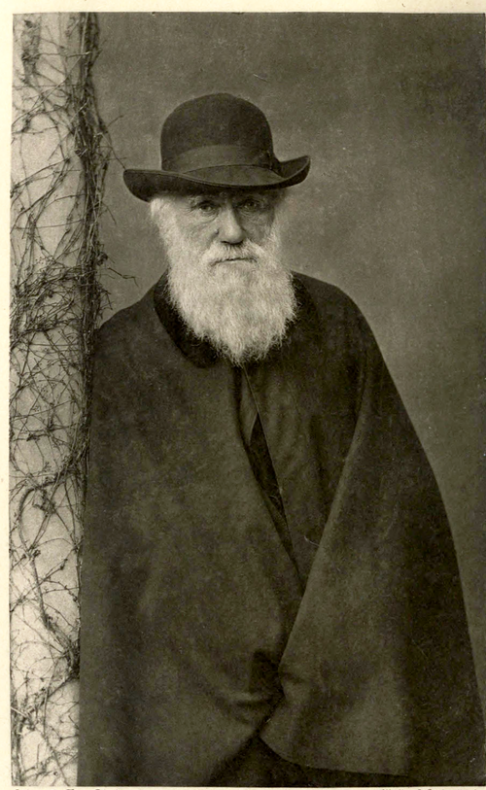

Painting of Charles Darwin, originally done in 1881, by John Collier, via Wikimedia Commons. Photo of Charles Darwin taken in 1881 by Messers. Elliot and Fry, via Wikimedia Commons. Which one do I like better, beauty or truth? Yes.

All I have to say is Loren Eiseley!

I read the transcript of your address yesterday and forwarded it to a friend. I suppose I’ll have to forward this along as well. It certainly made me think.

I personally like the idea of literary nonfiction, but I also agree with the idea that nonfiction writers mustn’t lie to their readers. I’ve kept my copy of that book by Jonah Lehrer on my bookcase so that I can remember how angry and betrayed I felt when I discovered he’d fabricated quotes, and how I felt I’d never be able to read the rest of the book because I’d never be able to trust him again. I felt the same way about “Never Cry Wolf” by Farley Mowat; a science writing professor had us read it and then, afterwards, assigned us to look up articles about it. When I discovered that it wasn’t truly nonfiction, I was overcome with righteous indignation.

I still think there’s room for beautiful writing in nonfiction science writing. But it’s a line that must be tread carefully, mindfully, thoughtfully.

Ann, I also dislike the term “literary nonfiction,” but I am puzzled by your point. All great writing, fiction or nonfiction, can be called literary. I know you’re not suggesting that John Hershey made up things in “Hiroshima” or John McPhee in his books.

Well, George, if I were a great writer you wouldn’t be puzzled by my point because I would have made it more clearly. I loved Hershey and still love McPhee and I wouldn’t suggest they made things up. I’m all for beauty in nonfiction. But I think defining beauty in terms of fiction can be a slippery slope for nonfiction writers. So I suggest they find the beauty in the trustable facts. At least I think that’s what I’m saying.

As a scientist by training, I found this very thoughtful. But there really is no such thing as a fact. And maybe the tools I’ll end up borrowing from literature will be tools to help my reader accept this. To help them love, or at least have a decent relationship with, “non-answers”. I think literature does this quite well.

Can you send a link to the transcript of your other talk? I loved this! It was fascinating and I will share on twitter etc.

Wendee, it was linked to in the post but here it is again and thank you for loving it and saying so: http://www.dcswa.org/literary-beauty-by-ann-finkbeiner