My studies and work in science were limited to the physical until last year, staying far away from those messy life sciences. When I started studying science illustration, a field which has traditionally accompanied biology, it became clear that nausea was something I had better put aside fast. In fact one could consider my year in the science illustration program as, amongst other things, a rather successful study in disgust management. When your school no longer has a specimen freezer due to an extremely unpleasant malfunction, you know you’re in for an interesting year. The changes in how I experienced disgust made me curious about this strange emotion and I wondered: if I can alter my reactions, are they really involuntary?

My studies and work in science were limited to the physical until last year, staying far away from those messy life sciences. When I started studying science illustration, a field which has traditionally accompanied biology, it became clear that nausea was something I had better put aside fast. In fact one could consider my year in the science illustration program as, amongst other things, a rather successful study in disgust management. When your school no longer has a specimen freezer due to an extremely unpleasant malfunction, you know you’re in for an interesting year. The changes in how I experienced disgust made me curious about this strange emotion and I wondered: if I can alter my reactions, are they really involuntary?

Disgust exists across cultures, it is distinctly human, and we experience it as a visceral, physical aversion. It seems instinctual–but it isn’t, at least not really. Children learn disgust–parents know they aren’t born with it. Studies have found only a kernel of disgust is an inherent behavior. Newborns (both humans and rats) display something called the “distaste face” when presented with a flavor that is bitter or sour. All other aspects of this emotion, however ingrained, are learned behaviors that stem from this same source. The area of the brain most activated in studies of disgust, including those that do not pertain to food related triggers, is the same area responsible for processing taste.

The first person to write about his observations of disgust was Charles Darwin. He noted the distinct facial expression that accompanies it, as well as the variety that exists in disgust triggers. He also noticed that triggers can vary widely between cultures. Darwin realized that disgust has an aspect of socialization. So what do I do when I’ve entered a society of biology freaks who get excited about dissections? I drink the Kool-Aid, of course… it just took me a bit of time and effort.

At the beginning of the year my class paid a first visit to UC Santa Cruz’s natural history collections. We were permitted to loan out specimens to use for our illustration projects. I too was excited about this prospect, until we arrived. Jars of lizards, drawers of animal skins and mounted specimens were everywhere and far closer than at a museum. The smell hit me quite hard, as did the glass eyes. When we stopped at an exhibit of local birds that had my classmates raving about the high quality of the taxidermy I felt perplexed and slightly nauseous. I have always been especially squeamish about medical things, but my relationship with non-human triggers is less straightforward. Taxidermy, though, never sat well with me.

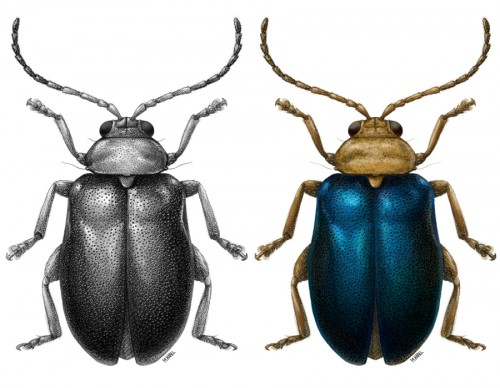

In an effort to avoid dealing with the stuffed animals, I borrowed a couple of insect specimens to draw. I wasn’t exactly comfortable with them, but I felt that the smaller the dead thing, the less of it there was to overcome.

The initial weirdness of looking at a giant bug started to raise questions. Forcing myself to study and stare at it intently caused my curiosity to somewhat dispel the shock of the thing. The miniature world we habitually overlook had started to draw me in. I don’t mean to suggest that I am now immune to insect related revulsion– I still hate roaches and millipedes with passion. (though technically millipedes are not insects, they ARE creepy-crawlies.) Parasites especially gross me out– shudder. But nowadays, I try to take a step back because even parasitism, which I find totally disgusting, can also be utterly fascinating.

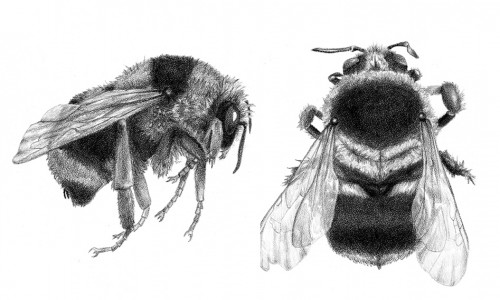

By now I’ve spent many hours creating painstakingly detailed entomological illustrations of bees and beetles under the microscope, and I can’t say I’m too pleased at some of my friends’ reactions to the finished work. Even bees can provoke an unpleasant response, and bees are the superheroes of insects! It’s interesting that these same people have no problem with butterflies– how easily those gorgeous wings distract us from a distinctly insect-y body.

By now I’ve spent many hours creating painstakingly detailed entomological illustrations of bees and beetles under the microscope, and I can’t say I’m too pleased at some of my friends’ reactions to the finished work. Even bees can provoke an unpleasant response, and bees are the superheroes of insects! It’s interesting that these same people have no problem with butterflies– how easily those gorgeous wings distract us from a distinctly insect-y body.

So what exactly is gross about insects? It’s tempting to say that our hatred of them is a defensive reaction to things that hold the potential for harm, but this isn’t a satisfactory answer. Only a precious few of the things we are repulsed by on a daily basis, actually threaten our person. Insects are just animals, and while some of them pose a contamination threat, most of them do not.

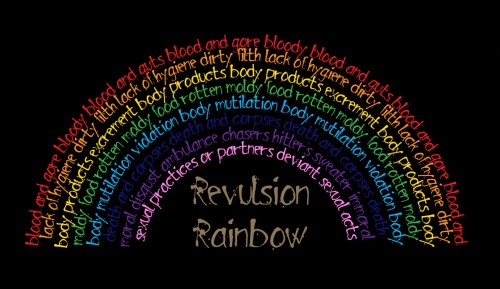

Rozin, Haidt, and McCauly study disgust and have divided triggers into distinct categories such as: foods, fear of contamination, animals, body products, death and proximity to corpses, poor hygiene, some sexual practices, and violation of the body. In addition they call attention to socio-moral disgust. Interestingly just about all languages on earth use the same word to describe core/physical disgust and the revulsion that is triggered by immoral acts. When I first read about socio-moral disgust I immediately thought of it as a distinctly different emotion, one somewhat detached from nausea. That was until I encountered the following example: the idea of wearing Hitler’s sweater. Don’t tell me this doesn’t bring back your playground fear of cooties.

A disgust trigger can fall into more than one category, so I tried to pinpoint what bothered me most about the things that repulsed me. This was a surprisingly complicated question to answer. While I have no desire to be near corpses, I found a fish dissection almost easier to deal with than stuffed specimens. It was clear that something else was bothering me: I don’t like the idea of flaunting the killing of an animal as a trophy, and this was at the core of my immediate reaction to taxidermy. When I learned that most of the animals in the UCSC collection were killed by accident or found by passersby and turned in for academic use, this concern lessened considerably. The core disgust of being near a dead animal, and the violation of the body involved in the process of preservation remained.

A disgust trigger can fall into more than one category, so I tried to pinpoint what bothered me most about the things that repulsed me. This was a surprisingly complicated question to answer. While I have no desire to be near corpses, I found a fish dissection almost easier to deal with than stuffed specimens. It was clear that something else was bothering me: I don’t like the idea of flaunting the killing of an animal as a trophy, and this was at the core of my immediate reaction to taxidermy. When I learned that most of the animals in the UCSC collection were killed by accident or found by passersby and turned in for academic use, this concern lessened considerably. The core disgust of being near a dead animal, and the violation of the body involved in the process of preservation remained.

While in school a friend of mine gave a talk about Carl Akeley, the famous taxidermist who made the dioramas at the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Akeley revolutionized taxidermy, effectively taking it from a hunter’s hobby to a form of scientific art. Akeley indeed flaunted the dead animal as a trophy, but he also revered and studied his subjects in incredible detail. And dear readers, I do not wish to make any of you uncomfortable by sharing specifics, but I must tell you that for me hearing in detail about Akeley’s innovations in taxidermy and his technique step by step, was far more interesting than it was disgusting. No one found this more surprising than me. After hearing the talk, my perception of many things that once repulsed me began to gradually change. By the end of the year I was able to sit through a taxidermy demonstration!

There are still plenty of things that disgust me on a visceral level, but there has been a definite shift in my reactions– almost like a delay to let my mind catch up with my gut. Rozin speaks the truth when he says that “disgust involves rejection based not on sensory properties, but on knowledge of the nature of something.” Learning about the things that we find gross is a surprisingly effective means of understanding both ourselves and the natural world.

_____________

Maayan is a graduate of the Science Illustration graduate program at California State University Monterey Bay and has created pieces for National Geographic Magazine, Wired.com and the Smithsonian. She spends her time illustrating science and nature and researching lightning at Tel Aviv University. She hopes to contribute to science communication through writing as well as art.

All the pictures above are hers, including the photo in the UCSC collection.

Very interesting!!

Terrific post, Maayan!

What a great post! I’ve loved insects and creepy crawlies since childhood, and yet cockroaches have made me dance and back away numerous times. When I finally saw them under the microscope in college, though, I understood how beautiful they were. The deep golden brown, their strong wings that let them fly at you when they _shouldn’t_, the perfect way their legs are situated to let them run at you maddeningly – I gained a new appreciation.

Your bee illustration is lovely. The wings are especially nice.

Thanks so much for the wonderful comments!

Victoria, I admit I have little desire to look at a roach under a microscope, though I view them as a formidable enemy…

Noa, thanks for the title inspiration, not sure if it was you or if you were quoting Tamar when you asked me!

good article