One night in May, I idly watched a scene from a rerun of an Animal Planet show called Mermaids: The Body Found. An affable-looking biomechanics researcher named Stephen Pearsall was recounting an analysis of a mysterious marine mammal carcass. In what appeared to be a dramatic re-enactment, the camera zoomed in on torn animal tissue, then showed men in lab coats staring at a CT scan of the creature.

One night in May, I idly watched a scene from a rerun of an Animal Planet show called Mermaids: The Body Found. An affable-looking biomechanics researcher named Stephen Pearsall was recounting an analysis of a mysterious marine mammal carcass. In what appeared to be a dramatic re-enactment, the camera zoomed in on torn animal tissue, then showed men in lab coats staring at a CT scan of the creature.

“I realized that this was like no tail we had ever seen before,” said Dr. Pearsall. “It became clear that this creature once walked on two legs. And there is only one animal that walks upright on two legs.”

Cut to another scientist, Rebecca Davis, who had studied the animal’s bones. “Hands,” she said. “They were hands.”

What the hell? I thought. Has Animal Planet found some fringe scientists who think they’ve discovered mermaids?

I soon realized that the documentary was fake, the animal remains were fake, and the scientists were fake. (The researchers are actors who have appeared in, among other things, Dredd, Space Janitors, and Spud 2: The Madness Continues.) Animal Planet acknowledged that the show was fictional. But the faux-umentary and its sequel Mermaids: The New Evidence, which aired May 26, still irked scientists and science journalists, who called the shows “the Rotting Carcass of Science TV” and “a giant middle finger to the public.” Viewers were distraught too: “I thought we had found some thing that was real,” wrote one commenter plaintively on the channel’s website. “Good luck animal planet, I will never watch your shows again!!!”

A clip from Animal Planet’s pseudo-documentary Mermaids: The Body Found.

But the show made me wonder if scientists ever had, in fact, claimed to find the remains of mermaids. A bit of Googling turned up nothing. Instead, I found mermaid lizards.

On the night of November 7, 1999, Japanese scientists surveying a nature reserve in Madagascar spotted a freshly-detached lizard tail twitching amid leaves on the ground. Lizards often shed their tails to escape the jaws of predators, and sure enough, the tail-less lizard was nearby. The team also discovered a dead lizard from the same species on the road.

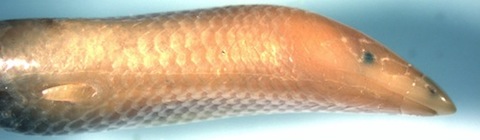

These pinkish, worm-like creatures had two tiny forelimbs, each with four claws, but no hindlimbs. Accordingly, the researchers named the species Sirenoscincus yamagishii: “siren” meaning “mermaid” and “scincus” meaning “skink,” a type of lizard.

Lizards have many strange limb configurations. Some species have lost all four legs, so they can better wriggle through dirt, sand, or leaf litter. Others have retained only their hindlimbs — an intermediate evolutionary step between four legs and no legs. But until the Japanese team’s discovery, the only known land animals with the “mermaid” body plan were worm lizards in the genus Bipes, which use their forelimbs to dig. Sirenoscincus’ forelimbs didn’t seem big enough for digging, so the researchers speculated that the lizards used them during mating.

About a decade later, a French herpetologist named Aurelién Miralles visited a zoological collection at the University of Antananarivo in Madagascar. He noticed two odd, unidentified lizards, about the size and shape of green beans, in a jar of alcohol. “I said, ah, excellent news! This is the very rare Sirenoscincus yamagishii,” he recalls. “So I was very happy.”

But when Miralles examined the specimens more closely in his lab in Germany, he realized that these lizards were not quite the same as S. yamagishii. The forelimbs on the Japanese team’s specimens had four “fingers,” while the new specimens’ limbs looked like small flippers. Since the animal was also pale, with tiny eyes, Miralles named the species Sirenoscincus mobydick, after the albino sperm whale in Herman Melville’s novel.

This species may be at a different stage of limb loss, says Miralles, who is now at the National Centre for Scientific Research in Montpellier, France. Sometimes lizards lose their “fingers” before the limb vanishes entirely. In 2011, a team in Thailand reported another new lizard species with only forelimbs — this time with two fingers — that was found beneath a stone in an evergreen forest.

These creatures have eluded discovery for centuries because they mainly live underground. For Miralles, “they are more exciting than mermaids, because mermaids don’t exist,” he says. “But these lizards, they are true. I have seen them.”

Image/video credits

First image: Everett Collection | Shutterstock

Video: Animal Planet

Second image: Falk S. Eckhardt

Third image: Philippe Geniez

Fourth image: Aurélien Miralles

So neat–and lovely that there are many magical creatures out there in world. (But my poor neighbor. He was so excited about that show he flagged me down to tell me about it. Also, it’s very possible that he was extremely high.)

Oh, poor guy. Did you have to tell him mermaids weren’t real?

Those little worms are surprisingly cute. I have heard that the mermaid myth may connect to sailors seeing manatees at a distance in the ocean — I don’t know how a manatee looks like a beautiful woman with a fish tail, but there it is.