These are down times for environmental journalism – or so you’d think, judging by recent news and the attendant hand wringing. The New York Times not only disbanded its environmental desk in January, but shut down its popular Green Blog early in March, also. Meanwhile the Washington Post’s Juliet Eilperin, longtime environmental correspondent a reportorial force of nature in her own right, decamped for the White House beat. Quite probably a lot of other bad-seeming things happened, too.

These are down times for environmental journalism – or so you’d think, judging by recent news and the attendant hand wringing. The New York Times not only disbanded its environmental desk in January, but shut down its popular Green Blog early in March, also. Meanwhile the Washington Post’s Juliet Eilperin, longtime environmental correspondent a reportorial force of nature in her own right, decamped for the White House beat. Quite probably a lot of other bad-seeming things happened, too.

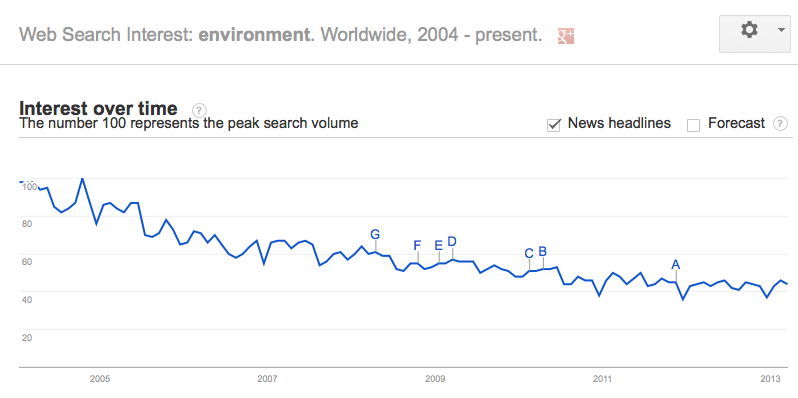

But the reality is that significant swings in attention paid to environmental issues are the norm, and not necessarily a sign of Some New Bad Thing. Sure, to young reporters who hopped on the recent Long Boom of interest in environmental journalism, a Google Trends graph such as the following, showing the relative volume of web searches for the term “environment,” could be alarming:

The environment hasn’t gone anywhere, of course, and we haven’t exactly wrapped up the problems associated with it. So why does the pattern above — a drop off by half in apparent interest over the last seven years — repeat for all sorts of terms related to key environmental issues?

It seems quite possible that the reading public simply has a finite attention span for bad news about green things. (To say nothing of a saturation point for gushing about new light bulb designs.) It’s a given on the green beat that environmental stories are hard to tell in compelling ways, since the issues at hand tend to be abstracted from readers’ daily lives, play out over very long periods of time and generally don’t so much resolve as they do fade into the background as still-worse environmental news breaks. Worse, they’re also confounded by bad actors and dishonest partisans on all sides.

“Sure,” you say. “But all those things are true of Israeli-Palestinian relations too, and we don’t see major papers shutting down their Jerusalem bureaus.” You’re right, of course. But here’s the thing: a lot of environmental journalism is boring. (There, I said it. Honestly, I thought it would feel more cathartic than it did.) Somehow, just slapping the rubric “environment” on a story is enough to conjure images of an earth-tone clad Al Gore droning away about sea turtles and Keeling curves. Even I feel exhausted by the sheer earnestness of it all, and environmental journalism is the animating passion of my life.

But still, I think there’s more to the apparent drop off in environmental interest than green tedium — and another attention span more relevant than the public’s. That’s right, I think I know what’s going on. But journalism can be a faddish profession (hyperlocal news, anyone?) and the current craze is for data journalism. So rather than call a source or simply trust my own experience, I decided to go data mining.

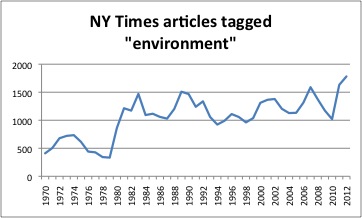

Admittedly, my bore hole isn’t setting any records. But a little time messing around with the LexisNexis database of digitized media articles can pay off nicely enough. Take a look at what happens, for example, when you search for articles tagged “environment” from the New York Times (since they started this latest round of hand wringing) between 1970 and 2012:

Three things are immediately obvious. First, the supply of environmental journalism in the Times is clearly unsteady over time. Second, while the sawtooth pattern of peaks and valleys is present throughout the time period, there was a major, persistent step up in the baseline number of environmental articles at the beginning of the 1980s. We might call this the Reagan Effect or, more correctly, the James G. Watt Memorial Plateau. (It follows just after the Disco Trough of the late 1970s.) And finally, there is a semi-regular periodicity of about 7-10 years between peaks. Extrapolating beyond the Times, this can mean only one thing: the demand for environmental journalism exhibits a classic boom-and-bust dynamic.

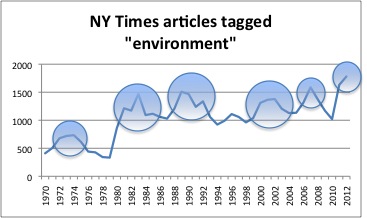

Looking closely, it becomes apparent that there were six primary peaks or booms in environmental articles in the Times between 1970 and the present. To wit:

From left to right, these peaks correspond tightly with the following eras of eco- consciousness: “hippies and whales,” “rainforests, tropical,” “rainforests, temperate,” “climate change, science,” “climate change, movie,” and the current one, “oh shit, it’s really happening.” (I suspect that the dip centered on 2010 is actually an artifact of enviro reporter Andy Revkin leaving the printed pages for his Dot Earth blog; more research is needed to confirm the pattern doesn’t repeat at comparable publications.)

The funny thing about these numbers, to me anyway, is how well they track my own working intuition about the waxing and waning of societal interest in environmental issues. Several days before I’d even thought to tabulate articles, I wrote the following: “By my experience, there have been peaks in environmental awareness from about 1982-85; 1990-91; 1999-2001; and this most recent one from about 2007-now-ish.”

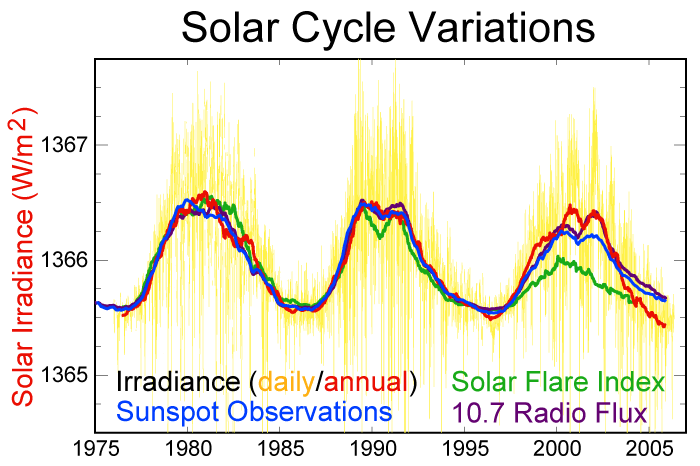

I didn’t start reading the Times regularly until the very late 1990s, either, so the correlation isn’t simply tautological. But is there something real going on behind the oscillations? Of course I, like you, first thought the driver must be solar activity and the 11-year sunspot cycle. And sure enough, there were major peaks in solar activity roughly corresponding to the onset of the Reagan Effect, peak rainforest interest, and the pre-Inconvenient Truth climate maximum:

Which proves nothing, other than that you can overlay a chart of solar activity over just about any periodic event and get a lot of hits.

So if it’s not sun spots, and it’s not just an inherent societal attention span, what else could be driving the ups and downs of environmental reporting, at mainstream outlets at least? I think it comes back to the faddishness of journalism. The news business is by definition about the pursuit of novelty. Sure, conflict, personal impact, horrifying disasters and political battles are nice too. But at the end of the day the great majority of reporters, editors, producers and managers in the media are fiends for the new.

Not five years ago, I remember, an enviro journalism colleague was grousing about carpetbagging political and business reporters hopping onto environmental stories, and big-footing more experienced, less wrong specialists out of assignments in the process. That’s not a complaint you’d hear now — “environment” may have been the fresh flavor recently, but today, well, it’s no data journalism.

If you’re distressed about a coming dip in environmental coverage, take heart. First, the record suggests that the beat will be back stronger than ever just as soon as something newly horrifying happens. Second — and this is new — you’ll still be able to get all the environmental reporting you want in the meantime, no matter what the mainstream journalism outlets do. From Mongabay.com to Grist.org, from Climate Central to The Daily Climate, from Ensia and to Yale Environment 360, and from scores of grass roots projects including my own collaborators at Generation Anthropocene and colleagues at the Bill Lane Center for the American West, the information niche is being filled, even as the attention niche dissipates.

I know the follow-on argument, that most people don’t read the specialist outlets, and that even the best environmental coverage in a niche publication never has the same society-mobilizing, politician-forcing impact that a big play in a major newspaper or magazine can. But here’s the thing: I’m not convinced those big media plays ever quite had that impact either. Finding out for sure would mean more data mining though, and I’m not sure if the trend will hold long enough for me to do the job.

—

Images

Turbulent sun: SOHO-EIT Consortium, ESA, NASA

Google trends search: March 21, 3013: http://www.google.com/trends/explore#q=environment&cmpt=q

LexisNexis search: March 24, 2013. Advanced search within The New York Times for articles tagged “environment”

Solar cycles: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Solar-cycle-data.png#file (You get that I’m joking about the solar cycles, right?)

“James G. Watt Memorial Plateau” — lol. So there’s a yin and yang to environmental journalism? In order to have the resurgence, you have to experience the decline?

Can you normalize your NYT chart by dividing by all the articles that appeared in the paper toal so you get a percentage, the ratio of environmental to its total coverage? That might tell you something too…

Ah, Dan. Now that’s starting to sound like actual research. AKA a lot of work. But yes, I think for the numbers to do much more than make me feel comfortable with my own hunches, you’d have to produce just such an index of enviro articles’ proportion of the total (by word count, or number of articles?). A section/page factor would probably have to come into it as well – 12 inches deep in a section is a lot different from 20 inches on the Biz section cover or the front page. And of course you’d have to expand beyond just the Times. And probably test a couple of other beats/sub-beats as well, to see if the pattern holds for other fields. But you know, work.

Liz, you ask a good question about the necessity of the dips and swings. I don’t think my wee search does much to inform that, but my hunch is that the dips in attention are important for recruiting fresh, energized new reporters to the beat and/or refilling the passion tanks of veterans. There’s nothing like being shut down for a few years to rekindle the fires…

Tom, is it possible that the peaks in EJ output are largely attributable to singular events (oil spills, hurricanes, etc.), rather than to general trends in environmental interest (rainforests, climate, etc.)? Not trying to create more work for you…just interested in your hunch about this. It might help explain the sawtooth pattern.

Thanks for the comment Dawn. I agree, it would be interesting to look at that – I imagine one could address it by developing a list of major environmental news events and subtracting them from the total record to see if the curve reverts to the baseline. I bet you’re right in that the curve would flatten noticeably, but my hunch is that there would still be identifiable pattern. For example, the Exxon Valdez oil spill (’89) does fall near the peak of the “rainforests, temperate” period, but Bhopal and Chernobyl (’84, ’86) fall in the trough between “rainforests, tropical” and “rainforests, temperate.” There are probably some confounding dynamics, though. On the one hand, Exxon Valdez was a domestic disaster, presumably leading to more coverage. And if environmental interest is already in a high period, presumably there would be more coverage for any given event than if interest is in a low period. (That last probably being a bigger factor below the threshold at which general interest publications and journos from other beats start to take notice, I would guess.)

Sun spots! I *knew* it was sun spots. When the vast global conspiracy to hide this knowledge is at last revealed, I will be vindicated.

Nice post Tom. My two cents: Reporters make a difference too. In the late 1980s to very early 1990s, Phil Shabecoff was the Times lead environment reporter, and he fought hard to get stories in the paper. Later, Keith Schneider came on board, and was similarly aggressive (and green groups hated some of his reporting). After each jumped or was pushed, I recall a lull as the Times seemed to reconsider its options.

I don’t share your optimism about third-party funded environmental reporting operations; I think they are as exposed to the boom/bust cycle as anyone, if not more so. If publishers have short attention spans, program officers at funders can have even shorter ones…

Cheers,

David Malakoff

Thanks for the thoughtful comment, David. You’re absolutely right about the impact of individual journalists (reporters or editors) at individual publications. You could track the space devoted science and environment coverage at many general audience publications by simply tracking which editor had responsibility for a particular section. (We’ve all worked under the conditions of personal quirks – no monkeys, at one publication; no sea turtles at another; no Guyana at a third.) I’d probably argue that most (most? much) environmental coverage has come down to the pushing of committed individuals over the years. The broader societal appetite for said coverage, in my experience, helps inform how successful that pushing is at one time or another. Of course, successful pushing at a big outlet such as the Times tends to have a knock-on effect too, as editors elsewhere pursue their tiresome passion for follow-the-leader assignments.

And just for the record, I’m not suggesting that third-party/foundation/university funded enviro and science news orgs are a massive solution or a bridge back to some hypothetical golden age. Just observing that they – along with for-free stuff such as LWON, educational stuff such as SAGE and Generation Anthropocene, advocate/activist outlets, and other models – are providing something into the niche, when mainstream pubs dip. And that’s different than it was in the olden tymes.