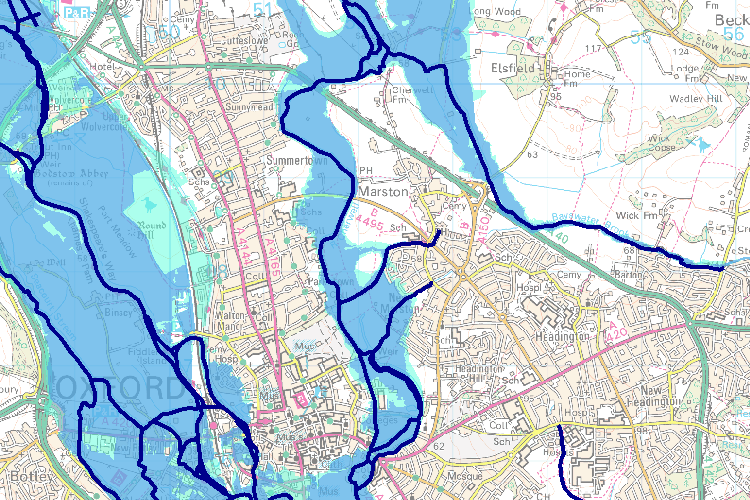

Water level rises, a river is fuller and fuller, until it’s something else, and the world is transformed. It’s a threshold effect: when quantitative sliding becomes qualitative step change. I’m lucky that on this map, my house falls in the light-blue rim of the darker floodplain, protected by a high-walled canal.

I’ll only get washed away in a 1 in 1000-year flood which, granted, could happen two years in a row. The main blue floodplain has a 1% chance of flooding in any given year, and insurance rates reflect this, but it’s only recently – on the timescale of a Medieval city – that planning and development decisions have reflected the danger. My son’s nursery is in a field that doubles as a flood storage area, where water is intentionally redirected to spare crucial infrastructure.

Living in a basin means being a receptacle for everything that flows downward, and Oxford is prone to collecting water run-off, as well as smog (doctors tell me there’s a condition known as Oxford Chest, which apparently is not another term for the Freshman Fifteen).

It’s hard to get great photos of flooding, because it’s usually dreary and raining, but I’ve done my best this week.

This river is usually so placid that the adjacent boarding school allows its students unsupervised rein of the water, provided the student can swim a pool-length fully clothed.

This river is usually so placid that the adjacent boarding school allows its students unsupervised rein of the water, provided the student can swim a pool-length fully clothed.

Unable to lean on large freshwater reserves like the Great Lakes, densely-populated islands have less leeway when it comes to water regulation. It’s not just the encroachment of rising sea levels around us, or unabsorbed rainfall streaming off of concrete and inundating rivers, the water is approaching from below as well.

Unable to lean on large freshwater reserves like the Great Lakes, densely-populated islands have less leeway when it comes to water regulation. It’s not just the encroachment of rising sea levels around us, or unabsorbed rainfall streaming off of concrete and inundating rivers, the water is approaching from below as well.

The London Basin is formed of 200+ meters of chalk formed in the Cretaceous period, on top of which is a much thinner layer of clay from the Paleogene era. The Chalk Aquifer is the main source of groundwater for the area, but unlike the Ogallala Aquifer in the American mid-west, the Chalk is in no danger of drying up. Since the 1960s, the urban water supply came from other places, and it took until the 1990s for the realization to hit. All that boring for water had been keeping Chalk Aquifer levels in check, and the ground under the city was starting to saturate.

Waters rising through porous chalk hits the impermeable barrier of clay above, and artesian pressure builds. Bursting through faults and fissures, the groundwater could destabilize buildings and tunnels, many of whose foundations predate modern engineering principles. To protect the infrastructure, the Environment Agency has started issuing abstraction licenses, encouraging boring for artesian water, like the Princess Diana memorial fountain, which doubles as the prettiest gutter ever built.