Last week, I left New York and headed for my home state of North Dakota. The plan was to fly to Minneapolis and then ride the rest of the way with my dad and stepmom, who were driving in from Wisconsin. Just before I headed to the airport, I sent my dad a text.

I’m not a hunter or a gun fanatic, but I thought it might be fun to shoot something. I envisioned us blasting beer cans off fence posts — father-daughter bonding. Instead we aimed at a cardboard box. I killed it dead. Turns out I’m kind of a crack shot despite my awkward stance. Apparently the skeet shooting I did in college as part of hunter’s safety paid off.

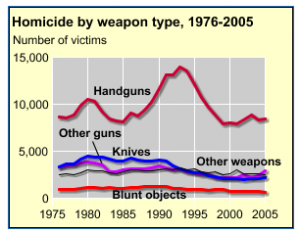

While I find guns thrilling, I also recognize that they’re designed to be deadly weapons.  Just last month, an army veteran shot and killed six people in a Sikh temple just outside Milwaukee. Two weeks before that a gunman murdered 12 people in a movie theater in Colorado. Gun violence isn’t as rampant as it once was, but it’s still a serious problem. In 2009, 31,347 people died of gun-related deaths. That’s slightly fewer than the number of people killed in car accidents. So what’s the solution? Would curbing access to guns prevent gun deaths? It’s a loaded question. (Pun intended.)

Just last month, an army veteran shot and killed six people in a Sikh temple just outside Milwaukee. Two weeks before that a gunman murdered 12 people in a movie theater in Colorado. Gun violence isn’t as rampant as it once was, but it’s still a serious problem. In 2009, 31,347 people died of gun-related deaths. That’s slightly fewer than the number of people killed in car accidents. So what’s the solution? Would curbing access to guns prevent gun deaths? It’s a loaded question. (Pun intended.)

These days, a mentally competent and law-abiding adult can buy a gun anywhere in the United States. You can conceal that weapon and carry it around with you anywhere but Illinois. In Arizona, which has some of the laxest gun laws in the country, you can tote a concealed handgun without a permit. You can slip it in your purse and bring it to the bar if you want. In Florida, if you perceive someone to be a deadly threat, the law says you can stand your ground and shoot even if you’re not in your own home.

Common sense suggests that having guns readily available leads to more shootings. So reducing the number of guns should curb gun violence. But this logical conclusion is actually really difficult to prove. Say you institute a ban in City X. If the number of gun-related deaths drops, how do you untangle whether the decrease was due to the ban or to other factors? Similarly, if gun deaths increase, that either signals that the ban didn’t work or that gun violence would have been worse had the ban not been in place. Linda Singer, the former Attorney General of Washington, DC, which instituted a ban on handguns in the 1970s, put it this way: “You can’t measure what didn’t happen,” she said. “You can’t measure how many guns didn’t come into the District because we have this law.”

In the early aughts, an independent task force conducted a systematic review of the research to assess the effectiveness of a variety of gun control measures, including gun bans, waiting periods for buying guns, firearm registration and licensing rules, and much more. But their conclusion was far from conclusive. “The Task Force’s review of firearms laws found insufficient evidence to determine whether the laws reviewed reduce (or increase) specific violent outcomes,” they wrote. “Much existing research suffers from problems with data, analytic methods, or both.” Sigh.

Both Chicago and Washington, DC, had handgun bans in place for decades. Both bans were recently struck down by the Supreme Court for violating the second amendment. But even if they hadn’t been, it seems naive to think that a ban on guns in a single city or even a single state could have much of an impact on gun availability. Brian Malte, director of legislation for the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence, told the LA Times, “states with stronger gun laws are undermined by states surrounding them with weak laws. Which means we need federal laws.”

But would nationwide restrictions really reduce gun violence? A thriving black market already exists for firearms, and it seems safe to assume that individuals who want guns to commit crimes won’t worry overmuch about the legality of having a gun. One of the lessons of the war on drugs seems to be that even draconian restrictions can’t make a problem go away.

“There are nearly three hundred million privately owned firearms in the United States: a hundred and six million handguns, a hundred and five million rifles, and eighty-three million shotguns. That works out to about one gun for every American,” wrote Jill Lepore in the New Yorker. That is a staggering number of guns. My dad owns a few that stay tucked away, unloaded and locked up. He takes them out occasionally to shoot up beer cans and cardboard boxes. But what of the other millions of gun owners? Can we trust that they’ll be as responsible?

**

That’s my dad in the first photo, and unfortunately I’m not sure who snapped it. My stepmom took the second photo of me with my dad’s pistol.

Whenever I travel in the States, I am gobsmacked by how easy it is to buy guns there. I don’t think it is any coincidence that the homicide rate was three times higher in the United States (5.5 per 100,000) than it was in Canada (1.8 per 100,000) in 2000, where I live. Give me stricter gun laws anytime.

See the link below for the stats provide by the Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics:

http://web4.uwindsor.ca/users/m/mfc/41-240.nsf/0/10ff8b04ff3a317885256d88005720f6/$FILE/ATT8BNDV/0110185-002-XIE.pdf

Heather, when I lived in Spain, I had a roommate who was from Denmark. Her mother was visiting the very same weekend that my parents were visiting. One evening we were sitting in the apartment and we heard a loud bang. It was only a firecracker, but it was loud and I jumped. The mother patronizingly said, “Oh, you must have thought that was a gunshot! But Europeans are civilized, not gun-toting heathens. Ha ha ha ha ha!” (Something to that effect.) Do Canadians feel the same way?

I agree that gun availability plays a role in gun violence, but I wonder how much of a contribution culture makes. Look at how rap songs glorify guns and gun culture in the States. Guns are a sign of manliness. They’re a right of passage, at least in some groups.

I really doubt that guns increase violence, if anything it is poverty. The less someone has the less they have to lose, so why not go out and rob a store or sell drugs? Best way to do that? Obviously get a gun. Same goes for gangs. You are unlikely to see a bunch of middle class boys out on the streets killing each other because more likely than not their parent(s) can afford to live on a forty hour a week job instead of having to work eighty hours to scrape by.

There’s also more violence in cities than in small towns. Why? Because people born in cities are crazy (literally, I think LWON mentioned the study of higher rates of mental illness in relation to where one grows up).

Finally, people need to feel safe, which is why so many die hard conservatives have guns, they’re expecting the government to come after them (frankly if I ever get a gun it’s because I don’t want the extremist types to have all the power).

I really don’t think that you can point to the culture of rap or poverty as explanations for the difference in homicide rates between the U.S. and Canada. Our radio stations here play tons of American music (and a lot of rap)and we watch all the major American TV programs and revel in Quentin Tarantino films here too. Moreover, we have real poverty here and a major drug problem in our large cities and glue sniffing in the smaller ones. The real difference lies in our stricter gun laws. They save lives.

I don’t think of Americans as gun-toting heathens, but I sure do question the right to bear arms, something enshrined, I believe, in the American constitution. That seems like an utter 18th century anachronism to me, something that should have been consigned to the rubbish heap long ago.

Sure, shooting tin cans is fun. I’ve done it myself. But the association between firearm availability and homicide rates is a comparatively easy topic. For example: http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/research/hicrc/firearms-research/guns-and-death/index.html

Countries that have high homicide rates tend to have a large fraction of those homicides committed with firearms.

The idea that it’s just impossible to say whether having more firearms actually leads to more deaths is similar to the argument that it’s just impossible to say for sure whether smoking leads to lung cancer. We need more research before we enact any public policy decisions that might negatively impact people’s opportunities to shoot one another.

Australia’s homicide rate is about 1.2 per 100,000. Only 13% of the homicides involved a firearm.

Like Canada, we have strict gun laws. Following a couple of high-profile mass shootings [Hoddle Street in 1987 and Port Arthur in 1996] the Federal Government instituted a massive gun buy-back scheme, during which my father handed in his [entirely illegal] Italian assault rifle, a weapon he had never fired.

In the past ten years, homicide rates have declined by about 3%, but it would be drawing a long bow to attribute that to the reduction in the number of firearms in the community.

In 2009–10, 54 percent of all victims knew their offender either intimately, or as

a family member or friend. 38% of female homicides were perpetrated by an intimate partner. This was the most common victim/offender relationship for females.

Males were most commonly murdered by friends—accounting for 30% of all male homicide victim/offender relationships in 2009–10.

Most murders occurred in the home [65%]. Blunt objects and knives were the most common weapons. Anecdotally, it is also much more likely that someone will survive such an attack rather than one using a firearm. This might partially account for the lower actual homicide rate in Australia [and I suppose also in Canada].