A few weeks ago I read the November 2011 newsletter of Roll Back Malaria – a partnership sponsored by the World Health Organization, the United Nations and the World Bank. It contained the following headline: “Nearly a third of all malaria affected countries on course for elimination over the next decade.” I’m not saying the glass is half empty, but it’s just not that simple.

A few weeks ago I read the November 2011 newsletter of Roll Back Malaria – a partnership sponsored by the World Health Organization, the United Nations and the World Bank. It contained the following headline: “Nearly a third of all malaria affected countries on course for elimination over the next decade.” I’m not saying the glass is half empty, but it’s just not that simple.

In this short sentence RBM conjured images of great progress against the world’s millennia-old malaria pandemic. So it may sound like nit-picking to point out that RBM’s list includes mostly economically developing countries that should have eliminated malaria a long time ago (former Soviet Republics; Turkey; Sri Lanka; North Korea; sub-regions of Indonesia, Thailand, India, China and Bhutan; several Pacific Islands; countries of the Middle East and North Africa; and from the Western Hemisphere, Mexico, Argentina and Paraguay). Add that not making the list are the world’s most malaria-burdened countries, all in sub-Saharan Africa – where 85 percent of the world’s infections and 90 percent of all malaria-related deaths take place – and I think a case can be made that RBM perhaps missed the mark.

For me, the RBM report that inspired the headline really highlights that global health programs are fighting two malarias and making great progress against only one of them.Technically, there are four types of human malaria and at least one monkey malaria that routinely jumps species to infect us. All these malaria-causing microbes are from the genus Plasmodia. But just two cause a vast majority of illnesses. Those two are called vivax and falciparum. The latter thrives in the climates and ecosystems of sub-Saharan Africa; the former thrives everywhere else. It is this one – vivax – that we’re making progress against, and have been for a hundred years. (To be exact, falciparum is found in other tropical and sub-tropical regions, but in relatively low proportions. And vivax does exist in Africa, but, again, in relatively low proportions.)

Vivax plagued much of the world prior to World War II, including the United States, northern Europe and northern Asia – places that are today virtually malaria-free. These regions eliminated it by getting people out of shacks, off mosquito-infested flood plains, and into properly built homes and decent-paying jobs. The last of it in the United States dried up in the 1930s and 1940s, when states like Georgia, with the health and development standards of rural Africa, were transformed by social safety nets and market-driven job creation.

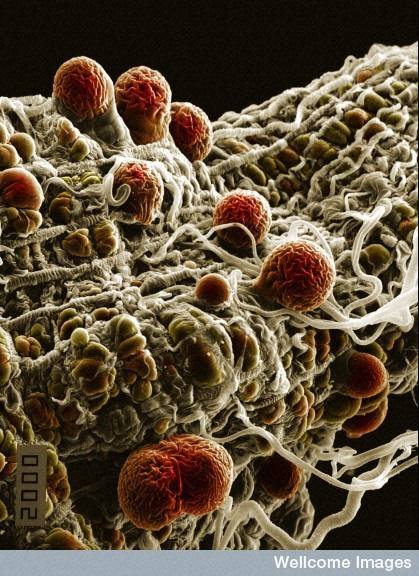

Such economic development disrupts the so-called cycle of infection because the cycle is inherently fragile. Malarial parasites – all of them – are wholly dependent on mosquitoes biting not once, but twice. The first bite drinks in a small handful of microbes that have infected a person long enough for them to reach a type of adult status. Once in the mosquito’s belly, the parasites sexually merge into egg sacs (all other parasites not making the jump slowly die off in the human blood stream). A week or two later – depending on air temperature – the sacs burst with infant parasites that swim into the mosquito’s saliva. With bite No. 2, they slip back into our blood to launch a new infection, during which they mature and migrate to our surface cells waiting to be sucked in again by biting mosquitoes.

Such economic development disrupts the so-called cycle of infection because the cycle is inherently fragile. Malarial parasites – all of them – are wholly dependent on mosquitoes biting not once, but twice. The first bite drinks in a small handful of microbes that have infected a person long enough for them to reach a type of adult status. Once in the mosquito’s belly, the parasites sexually merge into egg sacs (all other parasites not making the jump slowly die off in the human blood stream). A week or two later – depending on air temperature – the sacs burst with infant parasites that swim into the mosquito’s saliva. With bite No. 2, they slip back into our blood to launch a new infection, during which they mature and migrate to our surface cells waiting to be sucked in again by biting mosquitoes.

To keep the cycle going for all types of malaria, a lot of mosquitoes are needed to ensure that at least a few live long enough for that second bite. Which means the disease is transmittable only where people live unprotected from abundant populations of malaria’s night-feeding mosquitoes – of which there are about 40 species living all over the world. If anything disrupts the process – cold weather, land reform, screened dwellings, broad bed-net use, massive insecticide spraying – the microbes die off. And if the cycle is disrupted long enough, a region is considered to have eliminated malaria.

Vivax is distinct in that it rarely kills people, and survives temperate and semi-tropical climates in places like Eastern Europe, Asia, and South America by hibernating in the human liver during cooler months, coming out into the blood stream when larvae molt into mosquitoes. Infection cycles in these places are easier to break because they tend to be seasonal, not year round.

Vivax is distinct in that it rarely kills people, and survives temperate and semi-tropical climates in places like Eastern Europe, Asia, and South America by hibernating in the human liver during cooler months, coming out into the blood stream when larvae molt into mosquitoes. Infection cycles in these places are easier to break because they tend to be seasonal, not year round.

Today, vivax is disappearing in many of the RBM listed countries in large part because economic development and urbanization (away from mosquito-filled habitats) are reducing human-mosquito interaction, making malaria harder to sustain. Most of the RBM identified countries also have programs that deliver drug treatments, bed nets and/or insecticides to affected people. These low-tech malaria control strategies – developed during World War II – are quickening the natural tendency for malaria to steadily disappear as economies modernize. The RBM report helpfully tracks this dynamic.

The other malaria, African falciparum, presents a different story. Unlike vivax, it is quite deadly. It can clump up and stick like Velcro to the brain, triggering coma and death just hours after the onset of symptoms. It is best suited for tropical zones because it tends not to hibernate in the liver; mosquitoes must be ever present to keep the disease cycling. This makes sub-Saharan Africa ideal for this microbe. Mosquitoes bite year round and are the most efficient, durable, long-living and abundant vectors on Earth – in countries with among the most intense poverty known to man.

An entomologist I met in rural Tanzania in 2005 said he measured in one village an average of 2,000 falciparum-infected mosquitoes per person, per year – or 5.5 potential infectious bites per day. In these places, nearly everyone either acquires limited immunity to their local strains, becoming carriers of the microbes for mosquitoes to pick up and pass on to others, or they die. In such places, about 30 percent of child/infant mortality is caused by malaria alone, and much of the remaining mortality is at least in part from malaria. These populations are “seeded” with falciparum and have little hope of escaping the cycle. They live in mud huts, subsistence farm on rich mosquito habitat, are miles from decent health services, and suffer from a hundred other poverty-induced afflictions – cholera, dysentery, malnutrition – making malaria infections even more deadly.

An entomologist I met in rural Tanzania in 2005 said he measured in one village an average of 2,000 falciparum-infected mosquitoes per person, per year – or 5.5 potential infectious bites per day. In these places, nearly everyone either acquires limited immunity to their local strains, becoming carriers of the microbes for mosquitoes to pick up and pass on to others, or they die. In such places, about 30 percent of child/infant mortality is caused by malaria alone, and much of the remaining mortality is at least in part from malaria. These populations are “seeded” with falciparum and have little hope of escaping the cycle. They live in mud huts, subsistence farm on rich mosquito habitat, are miles from decent health services, and suffer from a hundred other poverty-induced afflictions – cholera, dysentery, malnutrition – making malaria infections even more deadly.

Global health programs can reduce infection rates in these places by pouring money into intensive treatment and bed-net distribution programs. But the money spent in Africa is rarely accompanied by the kind of economic progress seen in sister programs targeting vivax in Eastern Europe, North Africa, Southeast Asia and South America. As soon as the programs pack up and leave African countries, malaria returns in full force. And the political will needed to push for economic change is hard to find.

Falciparum malaria in Africa, the phoenix that rises from every attempt to eradicate it, is different from the malaria headlined by RBM. So, for me, the spin RBM chose for its “elimination” report used a narrow slice of the problem to imply a broad optimism. To more honestly address both of the world’s malaria woes, it should have read: “Of the world’s two malaria’s, one is on track for elimination in X countries; for the other, much, much, more is needed.”

That way we can remain optimistic about global progress against this disease, while also pressuring the world to recognize African malaria as part of a bigger system that needs new, broader-based strategies that involve bringing much-needed prosperity and health services to nearly a half billion smart and spirited, but horrendously impoverished African people.

______

Karen Masterson is finishing a book about malaria and World War II. She serves on the faculty of Johns Hopkins’ M.A. In Writing program and is a member of the Global Health Security team at the Stimson Center. She was awarded a Knight journalism fellowship in 2005 to study malaria at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Malaria Branch in Atlanta and with CDC investigators in Tanzania.

Photo credits: 1st: A village outside Ifakara, in rural Tanzania; it has 2,000 infectious mosquitoes (A. gambiae) per person, per year: by Karen Masterson

2nd: malaria parasites: Hilary Hurd, Wellcome Images

3rd: Anopheles gambiae: Kevin MacKenzie, Wellcome Images

4th: same village outside Ifakara: by Karen Masterson