Earlier this month, I gave an Ignite talk at the National Association of Science Writers meeting.

Earlier this month, I gave an Ignite talk at the National Association of Science Writers meeting.

(I also organized a panel on covering scientific controversies–click here to listen to/download mp3s of my interviews with panelists Gary Taubes, Jennifer Kahn, Jeanne Lenzer and Brian Vastag.)

I’ve had numerous requests to share my Ignite talk, and so in an attempt to replicate the experience, I’ve put together a storyboard/slideshow.

Here it goes…

I’m here to tell you what more than a dozen years worth of reader letters have taught me about science writing. I had a list of about 20 lessons, but I have only five minutes, so I’ve scrapped all but one.

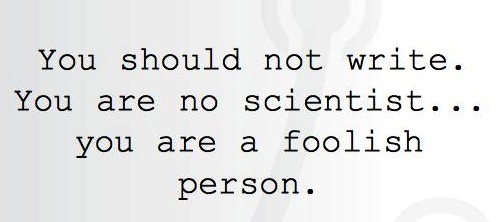

Which is—tell readers that they’re wrong about something they know in their heart to be true, and they will send you hate mail. For instance… I just wrote about how it’s tumor biology and not a person’s attitude that determines whether cancer their cancer progresses. A reader sent me this comment.

I’ve written numerous stories about how mammograms are more likely to turn a healthy woman into a cancer patient than they are to save her life. Those stories bring mail like this.

I’ve also written about climate change, which elicits letters like this one, which told me I needed therapy to…

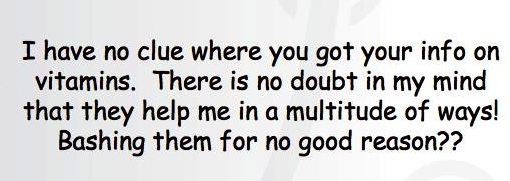

But these are nothing compared to the letters I got when I wrote about how taking a multivitamin won’t make you any healthier. Mind you, this was not ground breaking news. It was a long, slow accumulation of studies showing that vitamins don’t prevent cancer or heart disease or strokes or a bunch of other scary things. Oh did I get hate mail.

Of course, my editors helped things along. Here’s the coverline they gave the story.

Of course, my editors helped things along. Here’s the coverline they gave the story.

A lot people obviously never read any further. We got piles and piles of nasty letters, some sort of record.

Now it’s tempting to dismiss these angry readers as a bunch of idiots. But they’re not, and the truth is, I know where they’re coming from. I’ve been that person.

Now it’s tempting to dismiss these angry readers as a bunch of idiots. But they’re not, and the truth is, I know where they’re coming from. I’ve been that person.

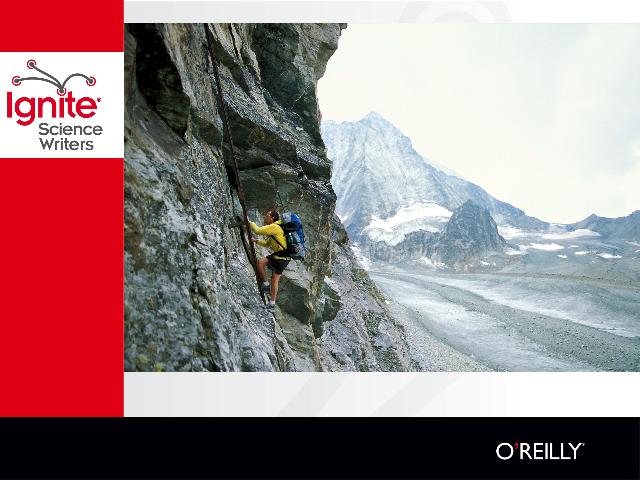

I’m married to an amazing guy. Dave is like those honeybees that always know the way back to the hive. Me, I’ve gotten myself lost in the Hearst building.

We’ll be hiking and we’ll come to a split in the trail and I’ll point one way and say, we need to go here. And Dave will say no, actually, this is the right way (as he points in the opposite direction). And I’ll insist that, no, this is the way.

And then he’ll point out that my way peters out below some cliff face. Which only pisses me off. The more evidence he shows me that I’m wrong, the more insistent I become — I’m right and he’s wrong.

And then he’ll point out that my way peters out below some cliff face. Which only pisses me off. The more evidence he shows me that I’m wrong, the more insistent I become — I’m right and he’s wrong.

And it’s not just me. This political scientist named Brendan Nyhan at Dartmouth has documented what happens when you show people evidence that their beliefs are wrong.

Instead of thinking, hmmmm, maybe I need to reassess here, what most of us do is go back and think about why we’d come to those beliefs in the first place. And in the process of doing that, we remember how great those reasons were and we end up reinforcing our original beliefs. Instead of re-evaluating, you become more sure of yourself.

Instead of thinking, hmmmm, maybe I need to reassess here, what most of us do is go back and think about why we’d come to those beliefs in the first place. And in the process of doing that, we remember how great those reasons were and we end up reinforcing our original beliefs. Instead of re-evaluating, you become more sure of yourself.

So when Dave tells me that his way is right and mine is straight up a cliff, I think, oh yeah? Well I’m smart, independent and capable, so therefore I’m correct. I would never point us in the wrong direction.

See, it’s never really about the hiking trail. It’s about some bigger story you’ve told yourself. I’m not taking issue with Dave’s direction. I know he’s right. But the factual mumbo jumbo he’s showing me clashes with the story I’ve told myself. I don’t like what it says about me.

See, it’s never really about the hiking trail. It’s about some bigger story you’ve told yourself. I’m not taking issue with Dave’s direction. I know he’s right. But the factual mumbo jumbo he’s showing me clashes with the story I’ve told myself. I don’t like what it says about me.

The idea that I could be giving wrong directions contradicts the vision I have of myself as a competent person. I’m sure that I know the right direction, because I’m too smart to lead us astray.

The idea that I could be giving wrong directions contradicts the vision I have of myself as a competent person. I’m sure that I know the right direction, because I’m too smart to lead us astray.

When Dave points out that I am directing us to a cliff face, here’s how I process the evidence. Dave’s way =I’m a helpless, dumb blonde. But I’m not a dumb blonde, I know I’m not, and so I reject his facts.

When Dave points out that I am directing us to a cliff face, here’s how I process the evidence. Dave’s way =I’m a helpless, dumb blonde. But I’m not a dumb blonde, I know I’m not, and so I reject his facts.

Which is the same thing that happens when the vitamin takers read my story.

They see the vitamin headline and they hear: your vitamin pill is a worthless scam, sucker! And then they think, no way! I’m no sucker — therefore this article is wrong. They reject the evidence.

Because the story they’ve told themselves is that they’re smart and “proactive” for taking the vitamin. In that story, it’s possible to protect yourself from scary diseases by taking a vitamin pill. And honestly, who doesn’t want to live in that world?

Because the story they’ve told themselves is that they’re smart and “proactive” for taking the vitamin. In that story, it’s possible to protect yourself from scary diseases by taking a vitamin pill. And honestly, who doesn’t want to live in that world?

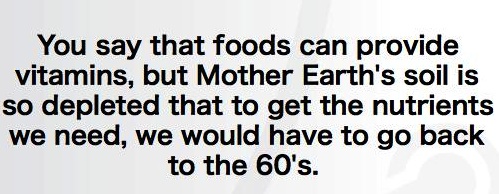

Of course, I heard lots of other stories too, about the soil and mother earth and evil pharmaceutical companies.

Of course, I heard lots of other stories too, about the soil and mother earth and evil pharmaceutical companies.

The bottom line is, people believe what they want to believe. It doesn’t matter what you’re writing about. People don’t want to know that they could do everything right and still die of cancer. I don’t want to know that I might not be as brilliant as I think I am. So we reject the facts and fall back on our worlds of truthiness.

And personal anecdote. Don’t even bother trying to overturn those with facts. No study will ever convince the people who are certain that the vitamin helped them. I’m not sure it’s possible to convince people with data that contradict their personal experience.

And personal anecdote. Don’t even bother trying to overturn those with facts. No study will ever convince the people who are certain that the vitamin helped them. I’m not sure it’s possible to convince people with data that contradict their personal experience.

But I know this: if you’re going to have any hope whatsoever, you have to speak to their story. Because that’s what you’re competing against.

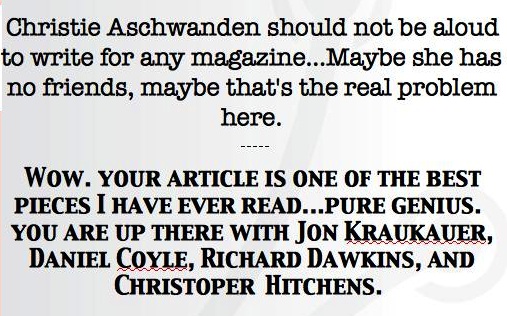

Here are two letters I received about the very same article. I know which one I believe.

Here are two letters I received about the very same article. I know which one I believe.

I’m Christie Aschwanden. Send me a letter!

(Or leave your comment below.)

***

Rob Frederick, multimedia journalist extraordinaire, was kind enough to take a video of my talk. Watch it here: Ignite Video

Photo credits: Christie at NASW by Carol Berkower.

Christie and Dave hiking by Patitucci Photo.

Brendan Nyhan from Dartmouth.

Christie running with confidence by JT Thomas.

Christie as a ditz, don’t ask…

I didn’t get to see this talk in Flagstaff, so I’m glad you posted this slideshow here. Daniel Kahneman makes some related points in his article in last Sunday’s NYT magazine: http://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/23/magazine/dont-blink-the-hazards-of-confidence.html ‘The confidence we experience as we make a judgment is not a reasoned evaluation of the probability that it is right. Confidence is a feeling, one determined mostly by the coherence of the story and by the ease with which it comes to mind, even when the evidence for the story is sparse and unreliable. The bias toward coherence favors overconfidence. An individual who expresses high confidence probably has a good story, which may or may not be true.’

Christie,

I really love your insight (and loved seeing your talk live!). I can’t help wondering — have you changed your approach to writing as a result?

A reader sent me here after I wrote about the intense frustration I felt arguing with my 7th grade son. I think this is really going to help me the next time.

The trouble would lie in assuming that this tendency meant that EVERY time he (or anyone else) vehemently disagreed with me, it would be because I was right and they deep-down knew it!

Jill, I have. As much as possible, I make an effort to acknowledge the false story and why it seemed correct. The problem is that this usually takes space, so it doesn’t always make it past the editors.

But showing readers they’re wrong is like punching them in the face. If you can give them a little hug first (tell them they weren’t stupid for believing the false thing in the first place) and hold them up while you’re swinging, it might soften the blow. At least, that’s the hope.

You’ve got Mail and you are BRILLIANT. So brilliant I am going to link to you. Full applause. For the same tune in a slightly different key, there is this >> http://terriermandotcom.blogspot.com/2011/10/in-land-of-blind-one-eyed-dog-is-king.html

P

Christie,

I was at your Ignite talk and thought it was the best by far. Possibly because, as a fellow writer and reporter, it was so very, very cathartic. Thanks for being brave enough to share. : )

Jennifer

Hi Christie,

I had blogged about an experience I had online with a medical professional. The conversation revolved around “bunk.” I was intrigued by how dearly he held and defended his beliefs.

You can read it here, if you are interested: http://blog.myphysicaltherapyspace.com/2011/10/do-physical-therapists-have-an-eminence-front.html

In all seriousness, how can we impact those making the recommendations if they believe in bunk?

Selena

I appreciate all the nice feedback.

Selena, thanks for the link. I like the idea of an eminence front. Thanks for sharing.

Christie,

Your talk/post will hit home to anyone who tries to write about evidence-based medicine.

I think you do terrific work.

Christie – thanks for the perspective, and the brilliant idea that I want to steal and apply to my own arena – health insurance, medical costs and what people think will make health care affordable.

I’ve been collecting information on this exact phenomenon since 2009 (the summer of health reform debate)about exactly this: People don’t care about facts and data especially if they don’t support the person’s own emotional position or beliefs. (that one is from Jim Lukaszewski).

You are absolutely right that stories trump data. How we tell the story is crucial to whether people “get it.” (another favorite: The plural of anecdote is not “data.”)

So, you’ve got lots of company. And sympathy (who’s good work hasn’t been burned by a questionable headline?) And please keep fighting the good fight.

Well, this explains why people get mad at ME when I point them to snopes.com after getting the latest “Obama is a secret Kenyan Muslim who conspired with George Bush to use nuclear bombs to destroy the WTC” email from them, instead of getting mad at the people who sent THEM false information in the first place. I’m sure, being human, I’ve reacted the same way. One solution may be to try to create your own self image as “I’m the kind of person who constantly re-evaluates their opinion in light of new evidence”, thus, admitting to being wrong in one area helps re-enforce your self-image of being rational, open-minded, and self-critical. Hey, it’s a start. 🙂

Christie,

I just got to the chapter in Panic Virus where Seth Mnookin talks about this very phenomenon (in his case, with respect to people believing with all their hearts that vaccines cause autism). It’s worth a read if you haven’t yet.

Examples of the Dunning-Kruger Effect.

I like to think that one of the best things one learns in education that actually calls you out when you get something wrong is to swallow the anger and remorse, stop, and wonder if the person telling you you’re wrong might be onto something. Here’s hoping.

I have become hyperaware of this phenomenon because my mother-in-law exhibits it in an exaggerated way. I am attempting to learn the fine art of expressing my opinion by giving her the impression that she is the one who thought of it. I have to be careful never to tell her outright that she is wrong. Even if she is, she will react with hatefulness. I think this is also part of the reason for the online rudeness phenomenon. Funny how it always has that “ad hominem” quality, too, isn’t it? Thanks for your thoughtful post!

Lovely article! Enjoyed this a lot, so true!

Ironically it’s also always the ignorant jerks like the ones you quoted who will use the “at least I have an open mind” argument when you’ve destroyed all their blathering, whilst closing their minds at the same time, it always cracks me up (though really you want to cry for humanity).

Thanks for your great work!

Yes, unless I try very hard (and then only sometimes!), I fall into the same trap. However, there is one notable exception. The Irish Independent has a columnist, Kevin Myers, who positively revels in taking unpopular stances on issues. I enjoy him most when he categorically disagrees with me – I know I’ll either have the pleasure of (in my mind) refuting him or else he’ll change my mind on a non-trivial matter. I actually enjoy the latter more. I’ve no idea how he manages something that my family, friends and colleagues can’t.

Regards,

David.

You’re an idiot! You don’t know what you’re talking about? How could I possibly be wrong about anything? It’s clearly you that’s wrong.

Wow, you hit the nail on the head, and not just for, um, “resistant readers.”

This same problem plagues science itself, and in fact goes right to the core: if we dare to extend current knowledge, we run the chance of uncovering our blunders, or getting a fleeting glimpse of the true size of our own ignorance. WIB Beveridge called it our “resistance to new ideas.” But those in the sciences don’t like to talk about it much, since it suggests that our own level of expertise, both as individuals and as a community, might be different than we’ve always imagined.

On the other hand, your above type of brutal self-criticism is the very thing which separates science from all else.

For similar fault-finding see: “Hidden Histories of Science” R. Silvers ed. (even w/one by Oliver Sacks.) https://www.google.com/search?q=hidden+histories+of+science And I see that Beveridge’s old book finally has a modern reprint: https://www.google.com/search?q=art+of+scientific+investigation

I appreciate the comments by Bill Beaty.

It is hard for me to understand how much of anything can be considered factual, given the amount of change in scientific “facts” over time. But by definition, scientists depend on the scientific method, therefore discounting anecdotal “evidence”, and basically expect the rest of us to do the same. But human nature will win over science when it comes to believing my own experience.

Just because you’ve researched a topic and come up with your conclusions, don’t patronize me if I don’t agree. Check again in twenty years. Or less.

Bill has a very valid point, that science needs to be open-minded and not protective of its facts as well, as proven by history.

Debbie, I agree it can get confusing fast. As Victor Hugo said, “Science says the first word on everything, and the last word on nothing.”

The scientific method is the most rigorous way to test a hypothesis, but the problem is that there’s always some uncertainty. Every study leads to more questions.

In the meantime, people have to make decisions in the real world. And that means making decisions based on incomplete evidence. Medicine is full of stories of, “we used to think X, and now we think Y.” It’s not that doctors or researchers are quacks, it’s just the way science works.

The difference between science and faith is that science is always open to new evidence.

What are the other 19 lessons?

This article explains a lot. I was at a health fare for the last 2 days as alamedarunners.com. I was given some stuff from GU to pass out to people who were out exercising or planning to start. People would ask me what a GU was. I would tell them it was concentrated calories that are easy to digest to get energy to your muscles. I usually eat them when I exercise for more than two hours.

Customer: Are they were good for you?

I would say no.

Customer: Are you healthy?

Me: Yes.

Customer: Do you eat them?

Me: Yes.

Customer: If you eat them and you are healthy, I will eat them and it will make me healthy. I am taking two.

Me: They will probably make you sick or you will spit it out and waste $3 per packet.

Customer: Grabs two and snags another as she turns to walk away.

That was a common exchange, over the course of two days.

I don’t know if it was the shiny packages, free stuff or people are just hoping for a magic potion but few people would listen to what I had to say. It ran against their beliefs. Imagine that.

This is made of God and Win.

http://health-med-news.com

This article explains a lot. I was at a health fare for the last 2 days as alamedarunners.com. I was given some stuff from GU to pass out to people who were out exercising or planning to start. People would ask me what a GU was.

Getting people to think is what your role is and I applaud your bravery to keep at it despite hateful mail. Getting individuals to be proactive in their care should lead to better outcomes and reduced costs. Ask about costs – because costs matter these days. Ask about alternative treatments. Perhaps exercise or diet changes have better health outcomes than a new medication for one’s condition. At Regence, we like to stress being inquisitive: http://whatstherealcost.org/video.php?post=five-questions

Well, I’m sorry it’s so frustrating for you, but it sure give me a good giggle.

You are wrong.

Great talk! I struggle with these issues myself, but perhaps in the opposite direction. I find myself paralyzed by the fear that I will accidentally mislead someone, so would be all too happy to re-assess my beliefs based on criticism. However, I haven’t yet encountered someone commenting on my blog and refusing to accept the facts I have laid out. Now I am better-prepared. Thanks!

All that you have described is explained by both behavioral economics and neuroscience. In 1979, Charles Lord coined the term “confirmation bias” describing just this finding. In short, any evidence that is pushed your way that contradicts what you currently believe is discounted, challenged or rejected. This work was updated using fMRI scans via Drew Westen and his writings on the subject (especially about political beliefs). Recent neuroscience findings also using fMRI scans show that when we are confronted with evidence that rebuts our beliefs, this creates “cognitive dissonance” which is actually painful (the same part of the brain that triggers physical pain lights up–the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) and the anterior insula). To alleviate the pain, we retreat to our beliefs rather than confront and engage the new contradictory evidence. See: http://www.sharonlbegley.com/our-brains-are-wired-for-hypocrisy

OR see… http://www.nature.com/neuro/journal/v12/n11/abs/nn.2413.html