There is something rare and elusive on the ceiling of Rouffignac Cave in southern France, something that at first looked like etchings of undulating snakes or bending waterways or even strangely shimmying humans, but that now turn out to be something far more ephemeral and wondrous to my eyes—works of art by very young apprentices: giggling, squirming, skittering Ice-Age children.

Rouffignac’s dark fingering passageways extend more than five miles into the limestone bedrock of the Dordogne region. Thirteen thousand years ago, Paleolithic humans held torches aloft as they penetrated deep into the cave, exploring its dark twisting passages and chambers. In the flickering light, these ancient cavers saw the raking claw marks of cave bears on the walls and stepped over scatterings of animal bones and gleaming flint nodules on the floor.

And for reasons unknown to us, these ancient humans left behind dozens upon dozens of etchings or sketches in black pigment of the giant Ice Age animals that frequented France’s steppes—woolly rhinoceroses, bison, horses, goats and woolly mammoths. Indeed, researchers counted so many images of mammoths that they eventually dubbed Rouffignac “The Cave of a Hundred Mammoths.”

And for reasons unknown to us, these ancient humans left behind dozens upon dozens of etchings or sketches in black pigment of the giant Ice Age animals that frequented France’s steppes—woolly rhinoceroses, bison, horses, goats and woolly mammoths. Indeed, researchers counted so many images of mammoths that they eventually dubbed Rouffignac “The Cave of a Hundred Mammoths.”

But those weren’t the only works of art in the cave. Early rock-art experts also took note of panels of squiggling lines on Rouffignac’s walls and ceiling, strange mash-ups of wriggling movement. But this artwork seemed much less important, certainly far less penetrable, than the exquisitely executed images of the mammoths and other Ice-Age fauna.

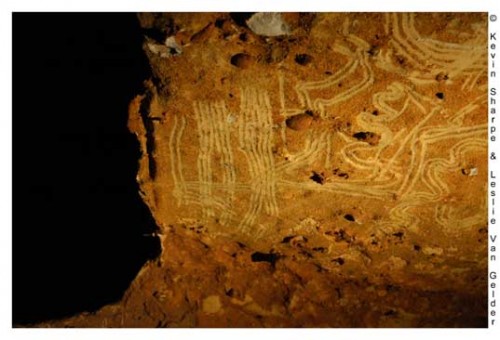

But a decade or so ago, two archaeologists—Leslie Van Gelder at Walden University in Minneapolis and her husband Kevin Sharpe at Union Institute & University in Cinncinnati—began taking a very hard look at the squiggles. Ancient artists, Van Gelder and Sharpe determined, had created the lines by drawing their fingers over a soft red clay on the walls and ceiling, revealing the white limestone or moonmilk (a type of mineralized cave deposit) below. Rock art experts call this artistic technique “finger fluting,” and to learn more, Van Gelder and Sharpe mapped and measured in detail the lines in Rouffignac’s dark chambers.

With this data in hand, the couple began searching for clues to the lines’ makers. By comparing the widths of the lines, for example, to the finger widths of living humans of different ages, Van Gelder and Sharpe discovered that young children between the ages of three and seven had created many of the markings. And in a second study, which examined the relative starting points of adjacent finger lines, Van Gelder and Sharpe managed to identify the probable sex of the artists. (Females tend to have index or second fingers that are as long or a little longer than their fourth fingers; males generally have index fingers that are shorter than their fourth fingers.) The evidence from Rouffignac strongly suggested that girls as well as boys had fashioned art in the cave – a finding that undermined an existing theory about the origins of the art in male initiation rites.

But how had children managed to leave their marks on ceilings that sometimes towered 1.8 metres above the ground in antiquity? No three-year-old child could ever reach so high. After studying the patterns of the lines, Van Gelder and Sharpe concluded that adults had held the children up or placed them on their shoulders so they could draw to their hearts’ content.

In 2008, Sharpe died, and recently Gelder began working with University of Cambridge doctoral student Jess Cooney, who presented a new paper on the art two weeks ago at a Cambridge conference. One of the most fascinating new findings relates to the finger fluting left by a two-year-old whose hand seems to have been steadied by a parent. “The flutings and fingers are very controlled,”Cooney told a reporter from The Guardian, “which is highly unusual for a child of that age, and suggests it was being taught. The research shows us that children were everywhere, even in the deepest darkest caves, furthest from the entrance.”

In 2008, Sharpe died, and recently Gelder began working with University of Cambridge doctoral student Jess Cooney, who presented a new paper on the art two weeks ago at a Cambridge conference. One of the most fascinating new findings relates to the finger fluting left by a two-year-old whose hand seems to have been steadied by a parent. “The flutings and fingers are very controlled,”Cooney told a reporter from The Guardian, “which is highly unusual for a child of that age, and suggests it was being taught. The research shows us that children were everywhere, even in the deepest darkest caves, furthest from the entrance.”

Is this the portrait of a cave artist as a young child? Did Paleolithic children begin their artistic apprentice around the time they learned to talk? Like many people, I have long marvelled at the sheer beauty and power of the horses and the bison of Lascaux. Thanks to the odd, wriggling lines of Rouffignac and to the research of a small team of archaeologists, we now have a glimpse into the mystery of their creation.

Photos: Rouffignac flutings, courtesy of Leslie Van Gelder and Kevin Sharpe. Woolly Mammoth, Royal B.C. Museum, courtesy rpongsaj. Lascaux II: Hall of the Bulls, courtesy Adibu456

Heather, this was completely charming. And it reminds me of your child-footprints post, https://www.lastwordonnothing.com/2011/02/21/whats-in-a-footprint/

which was also completely charming. Sniffle.

Double sniffle! Thanks, Heather.

Thanks so much guys! Sadly, archaeologists really struggle to find traces of children in ancient sites. Young children seldom made pots or stone tools; their clothes rarely preserve; and their toys–if they had any–seldom survive the passage of deep time. That’s why I love the footprints and now this research on ancient finger painting. I can just see those kids on their parents’ shoulders.

Fascinating and exquisite. I can only concur with other comments that far too little is dedicated to children in ancient research.

We say today that “children are our future”, was it not true then?

We need more of this type of information on the internet, accessible to children, rather than the silliness that seems to envelop and overwhelm them.

Blessings of Peace,

Heather —

Please accept my apologies for addressing you as Cassandra. Not that there is anything wrong with being Cassandra, of course.

Now I see that I even sent my comment to the wrong post. I think I’ve just moved beyond mild cognitive impairment.

Poor skeptico. We here at LWON are exceedingly tolerant of occasional cognitive impairment. In fact, when we see it in others, we are exceedingly relieved not to be the only ones.

skeptico, if you want to move your comment to this post, feel free. I’ll remove it from mine once you’ve pasted it here.

Fascinating!

heather —

Thanks for that nice humanistic interpretation of a scientific finding. What clever deductive methods those archeologists used! Some time ago one of you wrote a post on why ancient Europeans touch our imaginsations so much more than American First Peoples. My immediate reaction to that question was, “Because we have so much more cultural information about them, so much more that we can identify with, so much more that shows that they were like us.” This latest finding is a perfect example — what could bring long-dead people to life for us more effectively than evidence that they cared about and educated their children?

thanks, ann, for those kind words. just don’t tell my editor.

cassie — i’ve put my comment here. if you could wield your virtual eraser, that would be great.