In 2000, the last Pyrenean ibex died. These were mountain goat-like mammals with fierce black horns that scampered around the Pyrenees Mountains between France and Spain. Some cells had been taken from that last animal, and in 2009 the world learned that scientists had been able to clone the creature: a Pyrenean ibex kid was born to a surrogate mother, a hybrid between Spanish ibex and a domestic goat. (see the paper here.) The kid was delivered by cesarean section. It opened its eyes, stuck out its tongue, moved its legs about, and promptly died of lung abnormalities. Not exactly a complete success, but a milestone nonetheless. The technique has been proved in practice and all that remains now is to work out the bugs.

In 2000, the last Pyrenean ibex died. These were mountain goat-like mammals with fierce black horns that scampered around the Pyrenees Mountains between France and Spain. Some cells had been taken from that last animal, and in 2009 the world learned that scientists had been able to clone the creature: a Pyrenean ibex kid was born to a surrogate mother, a hybrid between Spanish ibex and a domestic goat. (see the paper here.) The kid was delivered by cesarean section. It opened its eyes, stuck out its tongue, moved its legs about, and promptly died of lung abnormalities. Not exactly a complete success, but a milestone nonetheless. The technique has been proved in practice and all that remains now is to work out the bugs.

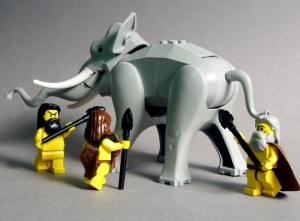

So, given that cloning extinct animals is feasible, should we do it? After all, humankind is responsible for an appalling number of extinctions, many of them in prehistory. We annihilated the dodo in 1662 and then snuffed out the Steller’s sea cow in 1768, but it was more than 10,000 years ago that we did our most spectacular slaughtering, picking off North American mammoths, mastodons, ground sloths, saber-tooth cats and cheetahs, European wooly rhinos, Australian giant kangaroos and wombat-like Diptrotodon among hundreds others. If we want to make good on all that, we had better order a hell of a lot of pipettes and 96-well plates.

So, given that cloning extinct animals is feasible, should we do it? After all, humankind is responsible for an appalling number of extinctions, many of them in prehistory. We annihilated the dodo in 1662 and then snuffed out the Steller’s sea cow in 1768, but it was more than 10,000 years ago that we did our most spectacular slaughtering, picking off North American mammoths, mastodons, ground sloths, saber-tooth cats and cheetahs, European wooly rhinos, Australian giant kangaroos and wombat-like Diptrotodon among hundreds others. If we want to make good on all that, we had better order a hell of a lot of pipettes and 96-well plates.

To clone a mammoth—which seems to be everyone’s favorite candidate for resurrection—one would need the following ingredients, compiled by science writer Henry Nichols in an excellent feature in Nature in 2008: a complete DNA sequence of even higher quality than what we have now, synthesized from scratch in chromosome form; synthetic mammoth mitochondria; a membrane to act as nucleus (perhaps from a frog); an egg to put it in (probably from an elephant); and a womb to implant it in, again from an elephant. Experts say that there are huge technical challenges with all the items on this list, and that we shouldn’t expect a mammoth at the local zoo any time soon. At this point, we don’t even know how many chromosomes mammoths had. But it could, in theory, be done. Alternatively, one could focus on extinct animals with living descendants, like the mighty auroch and modern cattle, then roll back the genetic changes that make them different, an approach LWON regular Tom Hayden explains in the October issue of Wired [there’s no link yet, but the story is available on newstands].

Another problem that I’ve talked over with Wildlife Conservation Society Institute director Kent Redford is that animals are not ever really alone. Mammals like mammoths and humans host thriving, complex communities of microbes on their skins, in their mouths and, especially, in their guts. This “gut flora”, when behaving normally, doesn’t hurt us but helps us break down our food and train our immune systems. Disorders from asthma to eczema to allergies and even obesity have been linked to the number and kinds of microbes in our guts. There are ten times as many microbial cells as human cells in your body, and microbial genes outnumber human genes by at least 100 to one (See here).

Animals and their microbiota are so tightly linked that some scientists think of them collectively as a kind of superorganism. Each species has its own suite of flora species that have adapted to it. When the mammoth went extinct, so, presumably, did all its little bugs. A cloned mammoth born vaginally from an elephant would likely end up with elephant microflora. One delivered by cesarean might have no bugs at all. What do we make of a mammoth superoganism if only one out 100 of its genes are authentic to the ecosystem that roamed the earth inside a hairy proboscidean skin 13,000 years ago?

And microbes aren’t the only things a baby mammoth would have gotten from its mother. Likely, the species were similar to elephants in that they were smart, social animals that learned from their elders how to behave and thrive. But the first cloned mammoth won’t have any elders. Like the sad cases of humans who grew up without interacting with their own kind, it would be alone, lost, un-socialized and likely unhappy. Rewilding champion Dave Foreman wonders, “would you really have something, or would you just have the body and not the mind, not the soul?”

So there’s a possibility that while cloning mammoths might make us feel better about our overzealous spear-hurling back in the Pleistocene, it would actually be cruel to the parentless, microflora-bereft creatures we would create.

So there’s a possibility that while cloning mammoths might make us feel better about our overzealous spear-hurling back in the Pleistocene, it would actually be cruel to the parentless, microflora-bereft creatures we would create.

In addition, the earth’s ecosystems have changed since all those big beasts went extinct. Suddenly reintroducing a menagerie of massive grazers, browsers, scavengers and predators wouldn’t neatly roll ecosystems back to the way they were before humans became the dominant ecological force on the planet. The ripple effects of their appearance might well even lead to new extinctions, and would certainly reshuffle the ecosystems we know from historical records—the very ecosystems we spend so much time tenderly protecting and restoring.

On the other hand, now that we’ve changed the whole planet with our extinctions, our incessant construction and resource extraction, our better living through chemistry and our atmospheric tinkering, we don’t really have any way of going back to 1491 or 1850, let alone the Pleistocene. It is all new, all changing. I’ve argued that the best way to be a conservationist in the 21st century is not to spend our lives looking over our shoulders at what seems like a lost paradise but to look forward, with clear goals and an open mind about trying new approaches. Maybe that means letting go of the dream of bringing back the big animals of our species’ childhood.

Or maybe it means saying, what the hell, let’s give it a try. Who wouldn’t love to look up, in 2100, from a high speed cross-country train to see a saber tooth cat leap on the back of a startled ground sloth, while a teratorn with 20-foot-wingspan circles above, licking its chops?

Or maybe it means saying, what the hell, let’s give it a try. Who wouldn’t love to look up, in 2100, from a high speed cross-country train to see a saber tooth cat leap on the back of a startled ground sloth, while a teratorn with 20-foot-wingspan circles above, licking its chops?

______________

Emma Marris is a freelance writer specializing in science and the environment. Her book on the future of conservation and the death of the Big Pristine is called Rambunctious Garden.

Photo credits: prehistoric toys – cryptonaut; dodo – Kaptain Kobold; mammoth – dunechaser; dinosaur – bolt of blue

i say what the hell, why not? but focus on the most recent human-caused extinctions (thylacine!!), along with the soon-to-be extinct (Rafetus swinhoei comes to mind) but a giant ground sloth would be pretty cool, as would a Testudo atlas. Maybe start small(ish) but either way, i repeat, why not?!

I’ve been pondering on this breakthrough for quite some time now. Yes it would definitely be fantastic to do some sort of reverse evolution by cloning. That’s a given. However, several questions came to mind. Top of my list is (which you have already touched on) how will they survive? The environment has immensely changed as well as the ecosystem. Now provided that they are able to finally adapt or maybe mutate into something more. (Like Mammoth Beta), how sure are we that they will not become a threat to humanity? Blame it on those Jurassic Park movies. hehe Also, their presence would, in some way, disrupt our current system that’s for sure. But then again, human as we are, this whole concept of reviving what has been lost is just too tempting. So despite these insecurities, I say, to heck with it! We’ll never know unless we try. Carpe Diem ;0

I seriously had to quit reading this article, as the author apparently subscribes to the idea that humans hunted the Wooly Mammoth to extinction as opposed to the myriad other far more realistic and likely reasons that they died out. The idea that a fraction of the amount of humans as existed in the past was able to wipe out an entire species is laughable. It is only due to the massive increase in technology and numbers that species have been able to be wiped out or nearly wiped out. Without long-range rifles or firearms of some kind as well as a massive demand for meat by a large influx populace, the American buffalo would still be running about in large numbers. The idea that a fractional amount of human beings armed with only spears, bows, etc. were able to hunt all the wooly mammoths, sabre-toothed tigers, etc. to death is absurd.

They had extincted in a natural way, and there is no reason to do cloning

I heard you speak on ABC radio (Australia). Thank goodness for your views. You have my vote… the middle path. Foxes and cats (main causes of crown fires) are a problem here in Australia, there have been mistakes but your realistic approach is the only option. Who knows where our plants and animals came from originally, and who carried them in ships?

Best wishes, Colin Horace Phillips