For the past two weeks, I’ve been riveted by an annual spectacle played out in an arena seating 22,547 of the most rabid tennis fans in the universe. The U.S. Open in New York City is one of the world’s four great tennis tournaments, and each year as the glorious days of summer begin to fade, I spend my evenings perched in front of the television, marvelling as David Foster Wallace once did at “the liquid whip” of Roger Federer’s forehand and “the human beauty” of a sport played at an almost godlike level. But beneath all this wonder and awe is something a little baser — a grim fascination that has its roots in something much, much older.

For the past two weeks, I’ve been riveted by an annual spectacle played out in an arena seating 22,547 of the most rabid tennis fans in the universe. The U.S. Open in New York City is one of the world’s four great tennis tournaments, and each year as the glorious days of summer begin to fade, I spend my evenings perched in front of the television, marvelling as David Foster Wallace once did at “the liquid whip” of Roger Federer’s forehand and “the human beauty” of a sport played at an almost godlike level. But beneath all this wonder and awe is something a little baser — a grim fascination that has its roots in something much, much older.

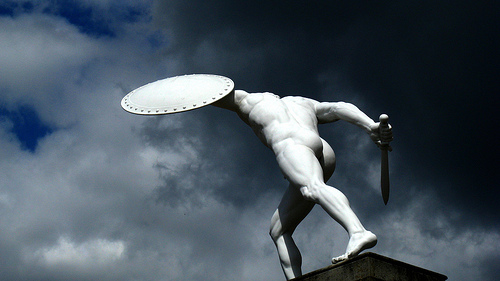

Tennis at its highest level is a sport of barely controlled aggression. It pits two rivals in a huge arena, all alone, without coach or spotter, sometimes for hours on end, sometimes nearly deafened by the roar of hostile fans, until one finally walks off the court as victor. Tennis at its best is not just about coolness under stress or selecting the right shot at the right time. At the very heart of these matches is the desire of one player to master another, to slowly strip away a strength to reveal a weakness, to grind down confidence and to break an opponent one punishing point at a time. It is a form of gladiatorial combat, nothing more, nothing less.

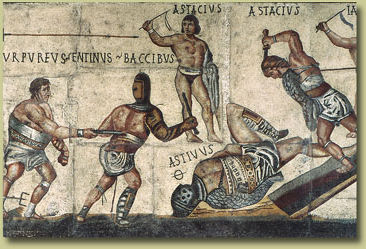

It was the Romans who invented gladiatorial combat, and they clearly preferred a grislier, more sinister version, one that might begin with a wild beast hunt and end with a small pile of human corpses being dragged out of the amphitheatre. But a great deal of what we know about this ancient combat today comes from the texts of classical writers and the odd bits of graffiti that adorn the walls of Pompeii and other Roman ruins. What was it really like to live and die as a gladiator?

It was the Romans who invented gladiatorial combat, and they clearly preferred a grislier, more sinister version, one that might begin with a wild beast hunt and end with a small pile of human corpses being dragged out of the amphitheatre. But a great deal of what we know about this ancient combat today comes from the texts of classical writers and the odd bits of graffiti that adorn the walls of Pompeii and other Roman ruins. What was it really like to live and die as a gladiator?

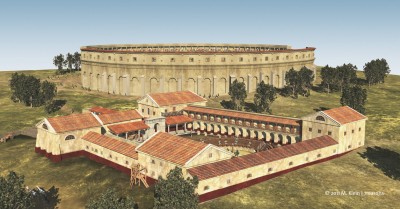

Over the past few months, archaeologist Wolfgang Neubauer and his colleagues at Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Archaeological Prospecting and Virtual Archaeology in Vienna have been looking into this very question. Poring over images produced by high-resolution ground penetrating radar, they have just discovered, mapped and visually recreated a previously unknown and intact Roman school for gladiators at the old site of Carnuntum, some 20 kilometers east of Vienna.

Carnuntum lay along the old Amber Road, an ancient trade route that wound from the dark forests of northern Europe to the shores of the Mediterranean. Protected by a large military base, this outpost flourished, eventually becoming a regional capital of 50,000, and by the second century A.D., it boasted a massive amphitheatre capable of seating 13,000 people.

Neubauer and his colleagues discovered the gladiator school this year while poring over the radar imagery of some suspicious-looking landforms just west of the amphitheatre. Buried under layers of sediment was a large rectangular compound enclosing an intricate tracery of stone ruins, sewage channels and lead water pipes. The most impressive of the ruins was a circular arena surrounded by wooden stands—the heart of a gladiator school.

Archaeologists have found other gladiatorial schools, but none so perfectly, eerily preserved. And already, careful analysis of the radar images is shedding light on the lives of the gladiators at Carnuntum. In cold weather, the gladiators there practised the art of swordplay and other martial arts in a large hall with a heated floor: the lanista, or owner of the school, seems to have been loathe to see his stable of fighters sit idle and grow rusty. On warmer days, they trained outdoors, wielding swords, spears and other weapons against a wooden dummy in the private arena. And when time permitted, they eased their aching muscles in a bathing facility that included warm baths.

Archaeologists have found other gladiatorial schools, but none so perfectly, eerily preserved. And already, careful analysis of the radar images is shedding light on the lives of the gladiators at Carnuntum. In cold weather, the gladiators there practised the art of swordplay and other martial arts in a large hall with a heated floor: the lanista, or owner of the school, seems to have been loathe to see his stable of fighters sit idle and grow rusty. On warmer days, they trained outdoors, wielding swords, spears and other weapons against a wooden dummy in the private arena. And when time permitted, they eased their aching muscles in a bathing facility that included warm baths.

But the movements of the gladiators were strictly controlled. According to classical texts, such schools served as prisons for a mixed company of slaves, war captives and convicted criminals, all of whom were forced to fight in the arena. The architectural footprint of Carnuntum’s school bears this notion out. At night, each gladiator slept in a cell-like room measuring as little as 5 square meters—about the size of a standard picnic table—to deter too much socializing and conspiring. And during the day, when the fighters bore weapons, the entrances to the arena were apparently sealed off to prevent escapes.

While the rare gladiator eventually won freedom from the arena by his prowess and wile, most died very young, after only a few matches. And even then, the school was well prepared. Neubauer and his team found the shadowy image of a cemetery near the school where the fallen gladiators could be laid to rest.

While the rare gladiator eventually won freedom from the arena by his prowess and wile, most died very young, after only a few matches. And even then, the school was well prepared. Neubauer and his team found the shadowy image of a cemetery near the school where the fallen gladiators could be laid to rest.

Just how their epitaphs might read remains to be seen, for archaeologists have yet to begin excavating there. But perhaps the inscriptions may be similar to one found elsewhere in the Roman Empire:

“To the reverend spirits of the Dead,” inscribed one grieving widow. “Glauca was born at Mutina, fought seven times, died in the eighth. He lived 23 years, 5 days. Aurelia set this up to her well-deserving husband, together with those who loved them. My advice to you is to find your own star. Don’t trust Nemesis [a Roman god of the hunt]; that is how I was deceived. Hail and Farewell.”

Translation of Gladiator Inscription, courtesy Keith Hopkins, author of Death and Renewal. Photos and Illustrations from Top to Bottom: Statue, Schloss Charlottenburg, Berlin, courtesy Frank M. Rafik; 5th Century floor fragment in Istanbul’s Great Palace, courtesy Wikimedia Commons; Illustrator’s reconstruction of gladiator school at Carnuntum, courtesy M. Klein/7 Reasons; Gladiator Mosaic on exhibition at Villa Borghese, courtsy Wikimedia Commons.

I found your comparing gladiators and tennis players interesting, and I definitely see the point. But the analogy only goes so far. Watching Nadal, Murray and Roddick complain about slippery courts and less than optimal scheduling is where this analogy ends!

Good point, Rufus! I doubt gladiators could go to officials in that way. But if you are watching the Federer- Djokovic match as I am right now, you can sure see the psychological warfare.